Aware of their reputation for forgiveness, some Amish are now asking, “are we as good at forgiving one another as the world is making us out to be?” David Weaver-Zercher, quoting some Amish contacts, indicates that they are conscious of their tendency to be hypercritical of one another, even as they quickly forgave the killer of five school girls in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, on October 2. They realize they need to work more on forgiveness within their own groups.

Speaking at a program in the “Common Ground Lobby Talk” series on Penn State’s University Park campus on Monday evening, November 6, Weaver-Zercher said that the Amish do, in fact, have disputes; in fact, some of their most difficult conflicts are internal ones. Sometimes the best ways for them to settle their conflicts are to simply avoid them.

Speaking at a program in the “Common Ground Lobby Talk” series on Penn State’s University Park campus on Monday evening, November 6, Weaver-Zercher said that the Amish do, in fact, have disputes; in fact, some of their most difficult conflicts are internal ones. Sometimes the best ways for them to settle their conflicts are to simply avoid them.

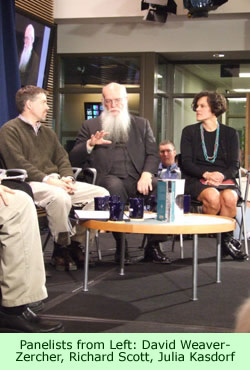

Weaver-Zercher, Associate Professor of American Religious History at Messiah College, joined four other experts on Amish life for a 90-minute panel discussion which had the title, “Plain People of Pennsylvania: Complex Cultures of Old-Order Mennonite, Amish, and Brethren Folk.”

Patty Satalia, an experienced producer from the University’s WPSU radio and television stations, hosted the experts, who also included Donald Kraybill, Interim Director at the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown College; Stephen Scott, Administrative Assistant to the Director at the Young Center; Richard Page, Associate Professor of German and Linguistics, Penn State; and Julia Kasdorf, a prominent poet at Penn State and Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing.

Several questions from the audience of about 200 people related to forgiveness, dispute prevention, and conflict resolution. Donald Kraybill indicated that when there are serious, unresolved disputes, the Amish will sometimes postpone their normal, twice-yearly holy communion services. In contrast to many other Christian churches, which view the ritual as a way for individuals to commune with God, the Amish understand communion as a process for cementing the peace and unity of the group. As a result, they may have to postpone having communion for several years, if necessary, until disputes are settled.

Several questions from the audience of about 200 people related to forgiveness, dispute prevention, and conflict resolution. Donald Kraybill indicated that when there are serious, unresolved disputes, the Amish will sometimes postpone their normal, twice-yearly holy communion services. In contrast to many other Christian churches, which view the ritual as a way for individuals to commune with God, the Amish understand communion as a process for cementing the peace and unity of the group. As a result, they may have to postpone having communion for several years, if necessary, until disputes are settled.

Kraybill also views the way Amish leaders are chosen, in part, as a strategy for helping to avoid conflict. He explained that they have one bishop, two or three ministers, and a deacon, all of whom are initially nominated by members of the congregation. Any man who is nominated by three different people is a candidate.

The nominated candidates each choose a song book, one of which has been prepared with a slip of paper, which indicates that the person who has chosen it is the newly elected official. Using lots as a process for selecting their leaders means, to the Amish, that God reaches down and makes the choices. Individuals might disagree with committee decisions or normal elections, but no one can dispute God’s decisions. That divine authority extends over the rest of the ministry of the chosen individuals, and helps prevent conflicts about the decisions they make.

Another questioner asked the panel to clarify the difference between forgiveness, which comes so easily to the Amish, and the shunning that they do to one another. Weaver-Zercher explained that the difference is between forgiving someone from outside the community and disciplining someone from within who has broken his or her vows. The issue prompting a shunning is usually not the trivial fact that someone within the community has violated one of the rules. Rather, the critical issue is the potential breakdown in attitudes that the violation of rules suggests, which they feel could weaken the fabric of the church.

Members of the panel provided a lot of factual information about the plain people. Kraybill, for instance, indicated that the total population of Anabaptists in the United States is 875,000, of which 237,000 live in Pennsylvania, roughly 27 percent of the total.

Roughly 42 percent of the state’s Anabaptists, about 100,000, are considered to be “old order”—people such as the Amish who preserve traditional religious beliefs and rituals and who reject a lot of the mainstream American culture.

Kraybill also said that the population of old order people in the U.S. is doubling every 20 years. The Amish now have 1570 church districts in 27 states and two Canadian provinces, Manitoba and Ontario. They are, in fact, surviving and thriving despite the challenges of living in the modern era. Their adaptation to modernity, by increasingly working at modern businesses, poses an extremely significant challenge for their culture, however.

In response to another question, Kraybill explained the voting patterns of the Amish. He said they are not discouraged from voting but they don’t hold office. He indicated that 13 percent of the Amish voted in the 2004 election, though they tend to take more of an interest in voting for local offices. Many don’t vote for president, since the president is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and they are reluctant to participate in helping choose that official.

When Satalia asked the panelists to summarize the evening, Kraybill responded that the Amish have a deep sense of belonging, order, identity, and meaning in their community. “The sense of being connected to a community is very valuable to the Amish,” he said. “The Amish are called to be servants to God.”

Weaver-Zircher replied that he is a little skeptical about transferring lessons from the Amish to mainstream life. It is difficult to figure out and generalize what we can learn from them. But, he said, “they do show it is possible to resist large cultural trends; it is possible to live an alternative lifestyle in America.”

Scott, an author and member of the Old Order River Brethren church, and Page, a scholar of the “Pennsylvania Dutch” language, also summarized their numerous comments during the evening. Julia Kasdorf, whose poems about the plain people highlighted the discussions, concluded with the observation that, when she thinks about the Amish, she thinks about people sitting around having conversations. As a child growing up in an Anabaptist household, she frequently sat under the dining room table listening to the adults talking. “What is important is that everybody in the community responds to questions with stories,” she concluded.