The Teesta River system is one of the biodiversity hotspots of India, and local Lepcha residents in the river valleys are agitating to stop the construction of dams that will destroy their ecosystem. Lingthen Gongthing, a Lepcha shaman, warns that “damming the Teesta, messing with her trajectory, arresting her flow, will cause a lot of destruction.” The Teesta drains much of the small north Indian state of Sikkim and, crucially, the eastern slopes of Mt. Kanchenjunga, the third highest peak in the world and a sacred spot for the Lepcha.

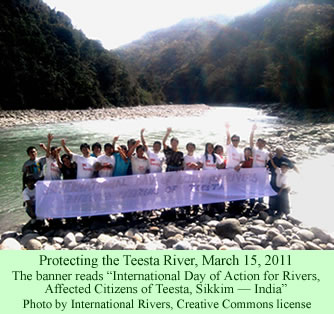

A filmmaker and leader of the environmental group Affected Citizens of Teesta, Dawa Lepcha, told a reporter last week that the construction work for building the projected dams, tunnels, and power plants in the Dzongu Reserve, the sacred heart of the Lepcha territory, “will have a profound impact on the environment.” A former forest minister of Sikkim, Athup Lepcha, believes that the short-sighted degradation of the environment will affect everyone, and will undermine the economic foundation of the entire society. Perhaps it will even destroy the ability of humans to survive, he fears.

A filmmaker and leader of the environmental group Affected Citizens of Teesta, Dawa Lepcha, told a reporter last week that the construction work for building the projected dams, tunnels, and power plants in the Dzongu Reserve, the sacred heart of the Lepcha territory, “will have a profound impact on the environment.” A former forest minister of Sikkim, Athup Lepcha, believes that the short-sighted degradation of the environment will affect everyone, and will undermine the economic foundation of the entire society. Perhaps it will even destroy the ability of humans to survive, he fears.

Kachyo Lepcha, a university lecturer and storyteller, asks a very simple question: “Why can’t India spare [the] Dzongu? How many such places are left in our country?” His question is based on the rich biodiversity of the state. According to an article last week summarizing the arguments of the dam opponents, 50 percent of the invertebrate and vertebrate species in India live in Sikkim, one third of which are endemics. That is, they are species that occur nowhere else in the world.

While the focus of much environmental activism of the past was on so-called charismatic megafauna, such as elephants and tigers, the issue now is to try and protect all of the interdependent communities of flora and fauna, including humans, which are seriously threatened by large, destructive construction projects. The 24 big dams planned for the Teesta River system would seriously threaten the interdependent web of life in the mountains and valleys.

Another serious issue is that weather patterns are changing rapidly, which threatens to decrease snowfall and rapidly shrink the glaciers in the eastern Himalayas. The article claims that the temperatures in northeastern India are likely to increase by 1.8 to 2.1 degrees Celsius (3.24 to 3.78 degrees Fahrenheit) in just the next 20 years.

The third major problem is the danger of earthquakes. Predicted by some scientists due to the tunneling and dam construction, the large quake last September may well have been the result of human activity. Geologists may not be able to predict exactly when or where earthquakes will occur after humans disturb the bedrock, but the construction might have prompted the earthquake.

Human-induced earthquakes have been occurring in the Northeastern U.S. A year-long series of minor quakes occurred last year in northeastern Ohio, apparently caused by the high-pressure injection of waste fluids used in hydraulic fracturing deep into the earth. The series was topped by a 4.0 earthquake which rattled Youngstown two weeks ago, on New Year’s Eve. Industry representatives of course denied any possible connection with their work, but the evidence suggested that the injections were probably the cause. The same sort of thing may have happened in Sikkim. In any event, Ohio officials at the beginning of last week stopped the industry from injecting the fluids into the disposal wells.

There is also a spiritual level to the debate in Sikkim. The bongthings, the Lepcha shamans, had warned that the gods of Kanchenjunga were angry about the destruction that people were doing on the flanks of the mountain. Whether the spirit of the great mountain was sufficiently angered, or whether the earthquake was purely a geological phenomenon, probably depends on ones religious perspective. Some Lepcha point to the fact that the number of deaths in the mining camps and construction tunnels during the earthquake indicates the displeasure of the gods.

Whatever the causes of the earthquake may have been, even Lepcha residents of Sikkim, who had previously accepted the assurances by the state government and the pro-dam advocates, suddenly began to have serious doubts. The benign goodness of the dams has been rejected by most Lepcha due to what has happened. Kanchenjunga appears to be wiser than the officials.