The Amish are starting to leave Lancaster County, according to an article published last week in the daily digital magazine Ozymandus (or “OZY” for short). The piece, written by Chris Scinta, indicates that the tourism industry, which has blossomed in the county, is so badly affecting the lifestyle of the Amish themselves that some have left, or are threatening to move away.

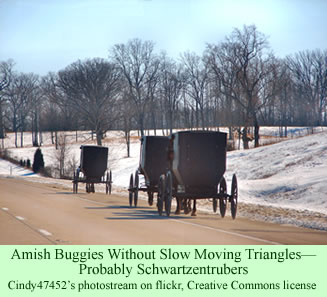

The typical tourist images of Amish country—horses plodding along country roads pulling buggies filled with Amish families dressed in their quaint clothing—may become self-defeating, the author suspects. The very factors that have prompted the rapid growth of tourism have led to rampant development that destroys the peace and quiet. Land prices have gone up so high that the Amish themselves can no longer afford to buy farmland for their children. They have the option of giving up farming or leaving Pennsylvania to find cheaper land, and quieter environments, in which to settle.

The typical tourist images of Amish country—horses plodding along country roads pulling buggies filled with Amish families dressed in their quaint clothing—may become self-defeating, the author suspects. The very factors that have prompted the rapid growth of tourism have led to rampant development that destroys the peace and quiet. Land prices have gone up so high that the Amish themselves can no longer afford to buy farmland for their children. They have the option of giving up farming or leaving Pennsylvania to find cheaper land, and quieter environments, in which to settle.

According to one research study conducted at Kutztown University in eastern Pennsylvania, the situation is serious—at least for the tourism industry in Lancaster County. “The commercialization of the Amish lifestyle has grown tremendously in recent decades, so much so that it actually threatens the viability of the very tourism industry it created,” the study reports.

Mr. Scinta quotes Samuel Lapp, an Amish man who quit farming and sold his farm near Intercourse 25 years ago. He told the writer that none of his sons wanted to go into farming themselves—they had seen others take paying jobs, earn money, and lead lives that did not involve so much hard work. Mr. Lapp decided that he did not want to continue milking the cows by himself.

Donald Kraybill, a prominent expert on Amish life, said that the conversion of Lancaster farmland into suburbs has put a burden on the Amish farming community. “It’s too many babies and too few acres,” he said. “The big danger is that the Amish here become so assimilated they end up not being Amish,” Kraybill added. They constantly deal with their non-Amish neighbors, their children interact with technology, and they start conversing in English rather than Pennsylvania Dutch, all of which weaken their commitments to their own culture.

But Mr. Scinta interviews one Amish man who has no plans to leave. Amos Bieler, who raises vegetables to sell at his store, Bluegate Farm Home Grown Produce, east of Lancaster City on route 30, told the author, “we like it here.” He said that the local government is trying to zone the area exclusively for rural life, in order to block suburbanization and development.

Although 25 years out of date, Donald Kraybill’s classic Riddle of Amish Culture (1989) still provides a lot of essential background to the story of possible Amish migration out of Lancaster County. He points out that the original settlement in the county has spawned many new congregations, both elsewhere in Pennsylvania and out of state.

The most basic question Kraybill addresses is that of Amish demography. He makes it clear in this book that the Amish will absolutely not consider limiting their population growth. “The Amish perceive birth control as reckless interference with God’s will, an unforgiveable attempt to play God” he writes (p.194). So as their numbers grow, their options have been to subdivide their farms, take factory jobs, take up other forms of work—or migrate to other areas. He explores those options carefully in the book.

It is clear from the brief quotes in the magazine article last week that Kraybill continues to monitor the patterns of the Amish, to see if they can cope with the constant pressures to join the mainstream, and to see how they can retain the many conditions that foster their peaceful society.