Last week a Canadian research team announced that they had found a sunken ship, the Terror, from the lost Franklin Expedition and that the knowledge of an Inuit man had prompted the discovery. Crew members of the research vessel Martin Bergmann found the wreck at the bottom of Terror Bay, located at the southwestern corner of King William Island fairly near the route through Victoria Strait where the Franklin Expedition ships had become frozen into the ice nearly 170 years ago.

Coincidentally, the first large modern cruise liner to sail through the Northwest Passage, the Crystal Serenity, described in news stories a few weeks ago, had sailed in open water through that same strait only four days before the discovery of the Terror. The blogs of the tourists aboard the Crystal Serenity had celebrated their occasional sightings of polar bears and views of distant ice.

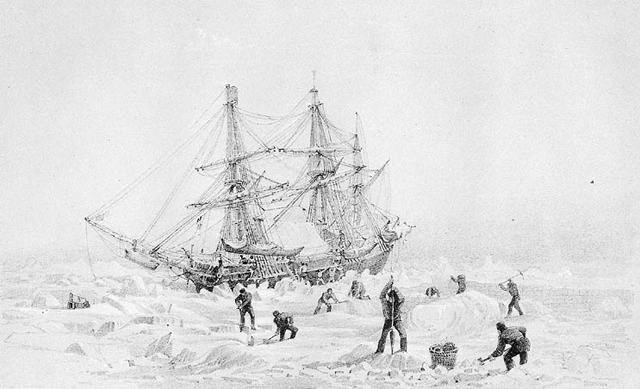

In 1845, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror, under the command of Sir John Franklin, left England, commissioned to map the fabled Northwest Passage across northern Canada linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The expedition disappeared into the icy Arctic vastness with all officers and crew members presumed lost. Two years ago the Erebus was discovered. News stories in September 2014 about that discovery highlighted the prominence of the Inuit oral memory of two lost ships from over 165 years ago. The news last week renewed a persistent worldwide interest in the expedition.

According to an article in the New York Times on September 13, the Terror had a strong connection with American history—it was one of the British ships involved with the attack on Fort McHenry in the Baltimore Harbor during the War of 1812, the battle which prompted Francis Scott Key to write what has become the U.S. national anthem, the “Star Spangled Banner.” The ship was used subsequently for various polar expeditions until it joined the Erebus in the ill-fated attempt to sail through the Northwest Passage.

The Times article made it clear that the input of an Inuit man, Sammy Kogvik, provided the key to finding the Terror. The Times quoted the chief executive of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, John Geiger, on the subject of Inuit knowledge of their environment: “The Inuits’ oral traditional knowledge around Franklin has been the only authoritative account,” he said, comparing their stories with the possibilities offered by modern research methods. He added, “Right from the early days, the Inuit had provided extraordinary insight, and it continues to this day.”

A longer account in The Guardian gave more information about the role of Mr. Kogvik. A crew member on the Martin Bergmann—he had joined it just the day before—Kogvik was chatting on the bridge with Adrian Schimnowski, Operations Director of the Arctic Research Foundation, the owner of the research ship. He told the expedition leader an odd story. He and a hunting friend had left Gjoa Haven, located on King William Island, one day about seven years ago on snowmobiles—not on their traditional kayaks—to go fishing together.

In the coincidentally-named Terror Bay, about 75 miles west of their homes, they saw a tall piece of wood sticking up out of the ice—a remarkable occurrence in a landscape that has no trees. It looked like the mast of a ship. He said he stopped to take some pictures of himself hugging the mysterious wooden object, but when he got home he discovered that he had lost the camera from his pocket. He decided to keep the sighting secret—the loss of the camera may have been an omen from the evil spirits that some Inuit believe have haunted King William Island ever since the Franklin Expedition tragedy. The National Geographic report on the finding indicated that when he went back later with another camera, the mast was no longer there.

Schimnowski listened to Kogvik’s account and, since Inuit observations and stories have been instrumental in so many Arctic discoveries, such as the finding of the Erebus two years ago, he decided to follow up and divert the Bergmann into the un-charted waters of Terror Bay. The Bergmann launched a small boat to do an initial search and after finding nothing for two and a half hours, the ship raised its anchor and started to leave the bay in order to resume its original course.

As it began heading out of the bay, the sonar on the ship suddenly revealed it was sailing directly above a sunken sailing vessel: the Terror. If the route of the Martin Bergmann had been more than 600 feet off in either direction, it would have failed to find the sunken boat. Mr. Schimnowski, interviewed by the New York Times from Gjoa Haven, said, “It’s like finding a needle in a haystack, and this is a very, very big haystack.”

The 10-member crew of the Bergmann of course were quite excited. They stopped and spent over a week quietly surveying the sunken shipwreck and sending remotely controlled cameras to photograph and film it from all angles, before publicly announcing their discovery last week. The 20-foot long bowsprit still points out from the bow, the ship’s bell is still there, a cannon has been spotted, the ship’s helm is visible, and even the exhaust pipe from a steam engine, installed in the vessel to help power it through sea ice, was exactly where the old drawings had indicated it would be.

Mr. Schimnowski said that the vessel “looks like it was buttoned down tight for winter and it sank. Everything was shut. Even the windows are still intact. If you could lift this boat out of the water, and pump the water out, it would probably float.”

The crew of the Bergmann worked to record everything they possibly could. Mr. Schimnowski told The Guardian how they had sent their cameras into the mess hall of the ship, found their away into some cabins, found the room on the ship where food was stored, and they even “spotted two wine bottles, tables and empty shelving. Found a desk with open drawers with something in the back corner of the drawer.”

Many of the news stories focused on the new information that the discovery provides about what exactly happened to the Franklin Expedition members in the late 1840s. What did they try to do to save themselves? Hints about all that are available, but at least part of the importance of the discovery is, once again, showing the Inuit knowledge of the land.

In a release, Mr. Kogvik indicated that he was delighted to see the ship again. “I am very excited, we found the boat I touched seven-eight years ago and then it vanished again. Gjoa Haven will be excited too because an Inuit found the boat so many years ago.” The news report from National Geographic indicated that the Inuit in Mr. Kogvik’s community were indeed celebrating the fact that one of their own had played such an important role in making a historic discovery.