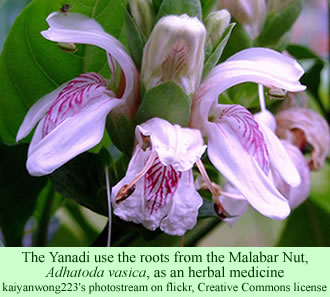

Last Thursday, the Herbal Folklore Research Centre in India uploaded a 12 minute video to YouTube that describes the importance of preserving traditional healing practices and natural herbal preparations used by the Yanadi in the Nellore District of Andhra Pradesh. Other literature indicates, for example, that Yanadi healers may prescribe for children a powder made from the roots of a small shrub, the Malabar Nut, Adhatoda vasica . It should be taken orally, mornings and evenings for one week, to help recover from fevers.

The video opens with scenes of a Yanadi village, surrounded by the rolling green hills of the Eastern Ghats in southern Andhra Pradesh. While the Yanadi “have centuries of traditional knowledge … it is now on the verge of extinction,” we are told. The camera follows people gathering herbs in the country and preparing them for their uses.

The video opens with scenes of a Yanadi village, surrounded by the rolling green hills of the Eastern Ghats in southern Andhra Pradesh. While the Yanadi “have centuries of traditional knowledge … it is now on the verge of extinction,” we are told. The camera follows people gathering herbs in the country and preparing them for their uses.

The narrator explains that healers only use the herbal preparations after they perform appropriate rituals. A healer, experienced in treating the diseases of children, says that he uses the dried stomachs of porcupines mixed with herbs to help cure disorders of the human stomach and to foster general well being. The camera focuses on the man and some pupils that he is training in his craft.

Then, the video concentrates on a Yanadi woman healer talking about her practice. She is proud that she has not taken any modern medicines—so far. The narrator says that customary names and traditional practices are normally kept secret. The names are only spoken quietly to pupils who are learning the practice of healing. The male healer then tells us that he observes the proper formulas before he treats anyone.

The video discusses changes that are occurring: invasions of industries, mining ventures, and forest removal, all of which are having a huge impact on traditional Yanadi uses of the land. These destructive forces prevent healers from entering the forests and gathering their plant materials. In fact, only some people from the Yanadi communities are now given permission by the government to enter the forests to collect non-timber forest resources. The government denies permission for older, experienced healers to enter the remaining forests or to collect plants for their rituals.

These factors are changing Yanadi lifestyles dramatically, the video claims. “The government policies are weaning them away from the forest,” one man says. The narrator explains that changes in the natural environment have forced the Yanadi to modify their economic activities, to become farm laborers in order to survive.

The closing two minutes of the video explain the importance of preserving the traditions of the Yanadi and the work of the Herbal Folklore Research Centre (HFRC), which is trying to help. These advocates of the tribal society have published monographs and articles in international, national, and local media to let people know what is happening.

The organization stresses the importance of health knowledge, the conservation of resources, and the role of healers in providing primary health care. HFRC has also trained the Yanadi in ways to increase the shelf life of their herbal products. The video closes with the statement that the “bio-cultural heritage of the Yanadi healers is at stake.”

Perhaps coincidentally, the Deccan Chronicle carried a news story last week about a research project carried out in the forests of Nellore District to catalog and describe the medicinal plants used by Yanadi healers.

Researchers from the National Institute of Indian Medicinal History and from the Sri Venkateswara University indicated that people living in those remote, forested regions have no access to modern medicines, so they use traditional herbal preparations to help treat their ailments.

The scientists appear to have taken the Yanadi healing practices seriously. G.P. Prasad, one of the researchers, described the project. He said that his team has documented not only the herbs the Yanadi use but also their medicinal properties. The catalog they prepared “will help us to study further … individual plants to find out whether they are of real medicinal value, and if so, in what dosage and in what form [they] should be taken,” he said.

The news story summarizes the characteristics of the 61 plant species gathered by the Yanadi and the uses the healers make of them, such as for menstrual problems, asthma, insomnia, constipation, fractures, cuts, wounds, eye diseases, indigestion, snake bites, ear aches, and so on. The full report, titled “Ethnobotanical Studies in Rapur Forest Division of Nellore District in Andhra Pradesh,” by M. Neelima and others, was issued in January 2011.

The report provides fascinating details about the uses of the plants, such as the Malabar nut mentioned earlier. For another example: a leaf powder from Ammannia baccifera is “administered orally for every one hour up to 10 hours [which] works as an antidote for scorpion sting.” Or, for Andrographis elongata: “Leaf juice with 2 to 4 drops of infant urine dropped into ear controls earache.” The report is available on the Web.

The authors, both of whom are at the Ǻbo Akademii University in Finland, open their work by describing the implications of values research, particularly the theories of Shalom H. Schwartz. His theories indicate that the values people hold are more than just abstract expressions of idealistic behaviors. Rather, they express people’s basic needs, they provide goals, and they motivate individuals to take effective actions in handling conflicts.

The authors, both of whom are at the Ǻbo Akademii University in Finland, open their work by describing the implications of values research, particularly the theories of Shalom H. Schwartz. His theories indicate that the values people hold are more than just abstract expressions of idealistic behaviors. Rather, they express people’s basic needs, they provide goals, and they motivate individuals to take effective actions in handling conflicts. The point of the study conducted by Miklikowska and Fry was to see how self-transcending values contribute to peacefulness in two different parts of the world—Peninsular Malaysia and the Western Desert of Australia. They start with the

The point of the study conducted by Miklikowska and Fry was to see how self-transcending values contribute to peacefulness in two different parts of the world—Peninsular Malaysia and the Western Desert of Australia. They start with the

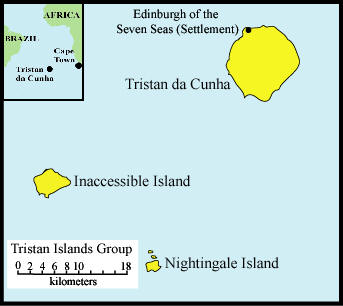

On March 16th, the MV Oliva, a 75,000 ton bulk carrier taking a load of soy beans from Brazil to Singapore,

On March 16th, the MV Oliva, a 75,000 ton bulk carrier taking a load of soy beans from Brazil to Singapore,