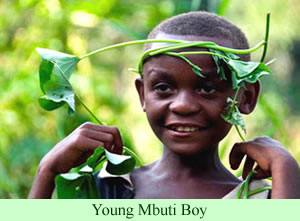

As part of its celebration this month of the installation of a new president, Dr. Nancy Leffert, Antioch University Santa Barbara is hosting an exhibit that focuses on the Mbuti people in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The exhibit, sponsored by the Tribal Trust Foundation (TTF), opened with a reception on Tuesday, March 1, at the university.

The university’s press release announcing the event indicates that the exhibit consists of recent photographs by Molly Feltner and older photos on loan from the Smithsonian by Eliot Elisofin. An alumna of AUSB, Barbara Savage, who is the president and founder of the TTF, gave the university the opportunity to be the opening venue for the exhibit, which will close at the end of the month.

The university’s press release announcing the event indicates that the exhibit consists of recent photographs by Molly Feltner and older photos on loan from the Smithsonian by Eliot Elisofin. An alumna of AUSB, Barbara Savage, who is the president and founder of the TTF, gave the university the opportunity to be the opening venue for the exhibit, which will close at the end of the month.

The university believes that the exhibition “will foster global support for preservation of the rainforest in the DRC and for protection of the indigenous people who have lived there sustainably for thousands of years.”

To its credit, the university announcement not only mentions the traditional, forest-based lives of the Mbuti, but it also describes the tragic problems the people are suffering from the persistent wars and violence of recent decades. The Mbuti may “consider the forest to be their great protector and provider and believe it is a sacred place,” but they have to confront the realities of today.

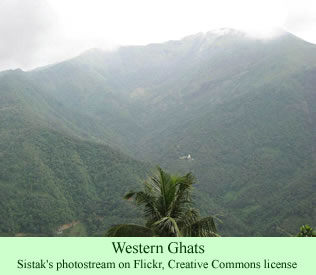

Deforestation, over population among the surrounding peoples, mining, and depletion of wild animals all threaten the existence of the Mbuti. Traders buy bushmeat to sell to the burgeoning Congo population, which harms the Ituri Forest where the Mbuti have traditionally lived and the Pygmies who remain in it.

As a result, since many Mbuti have had to resettle outside the Ituri, their forest-based traditions, culture, sustenance, and way of life have been virtually destroyed. They also are discriminated against by the larger, majority societies of the DRC, which typically view the short-stature Mbuti as inferior and primitive.

As a result, since many Mbuti have had to resettle outside the Ituri, their forest-based traditions, culture, sustenance, and way of life have been virtually destroyed. They also are discriminated against by the larger, majority societies of the DRC, which typically view the short-stature Mbuti as inferior and primitive.

The exhibit, located at 801 Garden St., Santa Barbara, California, is open for public viewing from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM Monday through Thursday and from 9:00 to 12:00 noon on Fridays, through March 31st.

Tijah Yok Chopil, the Semai woman, has become a leading advocate of Orang Asli rights, especially in Bidor, Perak state. She was quoted in several news stories in

Tijah Yok Chopil, the Semai woman, has become a leading advocate of Orang Asli rights, especially in Bidor, Perak state. She was quoted in several news stories in

The

The  Joanna

Joanna