Looters broke into the world famous Egyptian Museum on Saturday and ripped the heads off two mummies, but soldiers prevented them from getting to the gold mask of King Tutankhamen or the other priceless treasures of Egypt’s incredible history. The soldiers then secured one of the most important museum collections in the world.

Burning buildings, tanks in the streets, running battles between protesters and police—television images of the protests last week in Egypt quickly stopped the influx of foreign tourists and sent the ones already in the country fleeing. Over 12 million tourists per year visit Egypt and support an industry which represents 11 percent of the country’s GDP, roughly $10.8 billion per year. Tourism is one of the nation’s top sources of foreign revenue.

But they will probably return. Tourist numbers slumped after terrorists killed 58 foreigners at the Temple of Luxor in 1997, but they quickly rebounded. Similarly, the events of September 11, 2001, the start of the second Palestinian Intifada, and bomb attacks on resorts in 2004 and 2006 prompted immediate declines in the numbers of tourists, but they soon came back in ever larger crowds.

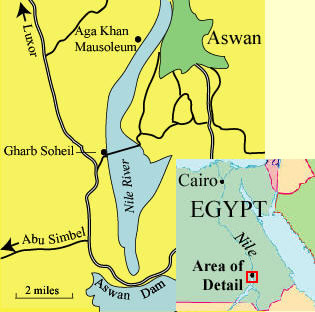

However, the welcome for tourists is not very strong among many Nubian people of southern Egypt, according to a news report last Thursday. A proposed resort project along the banks of the Nile immediately south of the city of Aswan caused controversy in 2009 among local residents. A businessman named Mansour Amer, who had developed a resort on the north coast of Egypt and another on the Red Sea coast to the east, proposed a large development on the banks of the Nile. It would have overlooked the Nile from the village of Gharb Soheil, on the west bank near the old Aswan Dam, and extended north as far as the Mausoleum of the Aga Khan, directly across from the city.

However, the welcome for tourists is not very strong among many Nubian people of southern Egypt, according to a news report last Thursday. A proposed resort project along the banks of the Nile immediately south of the city of Aswan caused controversy in 2009 among local residents. A businessman named Mansour Amer, who had developed a resort on the north coast of Egypt and another on the Red Sea coast to the east, proposed a large development on the banks of the Nile. It would have overlooked the Nile from the village of Gharb Soheil, on the west bank near the old Aswan Dam, and extended north as far as the Mausoleum of the Aga Khan, directly across from the city.

Opponents of the dam enlisted the help of Mohamed Mounir, a popular Egyptian actor and singer. The Secretary General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities investigated. He closed down the project by the end of 2009 because it would have been constructed too near the tomb of the Aga Khan.

The relief was only temporary. Another businessman, Ali Agha, started construction in 2010 near Gharb Soheil on still another tourist project. Local Nubian residents who discovered the construction knew nothing about the plans, and forcibly chased away the workers—at least temporarily. Hakeem, a young resident, said that a couple of people were arrested as a result of the scuffle.

Another local resident, Abdel Hakim Abdu, told the press that Ali Agha was not interested in talking with local residents. Instead, he went straight to the government of Aswan. He feels that the project is being imposed on them, which the local Nubian people don’t appreciate.

Gamal Ahmed Salahin, a local leader who had opposed the 2009 resort proposal, said, “We have always considered this area to be a natural protectorate; we don’t want to see it ruined with the construction of [tourism] projects bound to attract more investors ….” Nubian villagers worry that the developments will take away their lands.

That issue, land ownership, is probably the major concern of the Nubians. Yahia Taher, who owns a small hotel in Gharb Soheil, told the press that “land ownership among us is marked by tribal customs. Barely anyone has ownership contracts; by not consulting with the people in the area first, the governor did not take into consideration our culture and traditions, which led us not to welcome such projects.”

Ali Agha argues that he was not intending to harm anyone. He says he has the best interests of the local people at heart. He just wants to assist the area in making some progress. “It’s about time we move forward and develop,” he says. “Such a project is bound to positively affect the area since I only seek to employ Nubians. The idea is to build a prototype of a Nubian village for visitors to experience the Nubian life.”

Despite the worries of local Nubians, the developments are proceeding—or they were until the rioting began last week. Mohamed Hassan, a spokesperson for the Governor of Aswan, told the press that the project, and numerous others, were going to move ahead. Asked about environmental concerns over the development, he said there was no issue. Large scale projects encourage better environmental protection, he argued.

Salahin, the local leader, counters: “People have been trying to tell the governor that we do not seek to push investors away. [What] we don’t want to see is investors coming with big projects that stand to ruin our environment.” He adds that the Nile already suffers from pollution, some birds are already gone, and there are too many boats in the water. He believes it will get worse. Whether the rioting will slow down the construction, and thus help protect the Nubian environment, remains unclear.

The Nubians are used to being ignored by the Egyptian government, a situation that dates back to the 1960s when much of Old Nubia was destroyed in order to construct the Aswan High Dam. Taher expresses frustration that is typical of the Nubian people. “We are not willing to stand by and see something similar happen again for the sake of tourism projects. The government has not been making decisions with our best interest at heart for too long. It’s time this changes.”

Local resident Abdu expressed thoughts that may be typical of many Nubians: “If people here continue to feel their concerns are being sidelined, then you can’t expect us to remain quiet. Many [of us] are willing to die to protect our land.”

For 50 years, beginning in the early 1950s, Marshall chronicled their lives, capturing with his films, which were based on unique, lifetime friendships between filmmaker and subjects, the passing of their old ways and the radical changes of their society. Certainly one of the most influential ethnographic filmmakers of the past century, he set a high standard for recording human experiences.

For 50 years, beginning in the early 1950s, Marshall chronicled their lives, capturing with his films, which were based on unique, lifetime friendships between filmmaker and subjects, the passing of their old ways and the radical changes of their society. Certainly one of the most influential ethnographic filmmakers of the past century, he set a high standard for recording human experiences.