Facebook and the Buid society in the Philippines both have peaceful cultures based on a surprisingly similar approach to interpersonal relationships. They both foster indirect communication. The comparison is easy to explain.

Many people compare socializing on Facebook to having a “water cooler conversation.” There is even a group page in FB with that name. A Google search for “water cooler conversation” AND Facebook yields about 80,000 results. But the analogy is inexact.

Yes, people send messages to select groups, or to single individuals, and of course we have online chats at times. But most people direct their comments to their entire group of “friends”— scores, hundreds, or thousands of them. “I gave my dog a bath this morning.” Maybe someone will care. The banality of a lot of the postings is part of the charm of the whole phenomenon. How many of the 575 “friends” really care about the suds, or the pooch? It doesn’t really matter.

The peaceful aspect of the social networking process is the fact that so many of those messages are NOT, in fact, directed at specific individuals. They are sent to the entire, undifferentiated group. Everyone can read them—or not. No one has to answer. Some click “like”, most don’t; some comment, most don’t. All of that is OK within the social networking world. And it is amazingly similar to the approaches of many of the peaceful societies. In fact, for a lot of the nonviolent peoples, talking to groups rather than individuals is one of their more important strategies for maintaining harmony.

There is something about the direct request, the direct comment, the direct action, that may raise the possibility of irritation in some listeners. Perhaps they should be called “sensitive” peaceful societies—groups of people who are fearful that something an individual does, or says, may cause offense. Indirection is the name of the game among those folks. Individuals will laugh a lot, keep conversations light, and approach issues with others without directly coming to the point, by dropping hints, which the other people may guess at and respond to—or not. Replies are equally indirect.

A good case in point is the Buid, also spelled Buhid, a society in the mountains of southern Mindoro Island that is sensitive to one-on-one, dyadic relationships to an extreme. In their communities, people often address comments to a group, or sometimes to a distant mountain, so that no one individual is put on the spot, no one has to answer. If requests are unanswered, so what? No one is hurt and peaceful relations are maintained. That is the overriding concern of that society.

Facebook society is strangely similar. People make comments broadly to big groups of friends who may or may not reply, as they feel so moved. This pattern contrasts with emails, phone conversations, and even discussions around water coolers, where everyone tends to be more pointed. That directness, that getting right to the point, that habit of cutting to the chase, may, in the view of the peaceful societies, pose a very slight risk of confrontations. Best to avoid them and be indirect. Make comments to the whole.

Facebook was accused by a New Jersey preacher last Thursday for fostering adultery. On the contrary, is it, perhaps, the forerunner of a global peaceful society of 500,000,000 people? Is that last question indirect enough? After all, it is addressed to a large group of people, the visitors to this website, rather than to specific, named friends. No one needs to respond.

But if anyone does want to reply, the number of fans of the Facebook “Fan Page” for this website, established six months ago, continues to grow, a cause for appreciation on this Thanksgiving holiday in the United States. Feel free to leave a comment there. Or not.

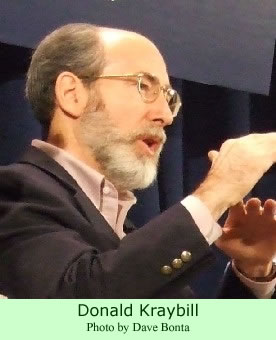

Mr. Stark, the reporter, also interviewed Donald Kraybill at the Elizabethtown College for some information about these changes in Amish enterprises. Kraybill, a famed authority on the plain people, explained that there are now about 30,000 Amish in Lancaster County, a population that will double in 20 years. Traditional jobs are getting hard for them to find. He says that entrepreneurs who have moved into new businesses and adopted advanced technologies have been criticized by other Amish people.

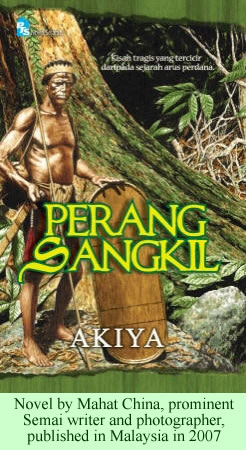

Mr. Stark, the reporter, also interviewed Donald Kraybill at the Elizabethtown College for some information about these changes in Amish enterprises. Kraybill, a famed authority on the plain people, explained that there are now about 30,000 Amish in Lancaster County, a population that will double in 20 years. Traditional jobs are getting hard for them to find. He says that entrepreneurs who have moved into new businesses and adopted advanced technologies have been criticized by other Amish people. He published books of poetry, short stories, and finally a novel, Perang Sangkil, which was published in the Malay language by PTS Fortuna, in Selangor, in 2007. In 1976, he discovered that he also wanted to capture the experiences of the Orang Asli in photographs as well as in his writing. He started collecting photographic equipment and taking pictures, capturing the ordinary daily events, celebrations, joys, and tragedies in the villages. Exhibitions of his photographs portray these events for the outside world, so others can appreciate the aboriginal ways of life, he feels.

He published books of poetry, short stories, and finally a novel, Perang Sangkil, which was published in the Malay language by PTS Fortuna, in Selangor, in 2007. In 1976, he discovered that he also wanted to capture the experiences of the Orang Asli in photographs as well as in his writing. He started collecting photographic equipment and taking pictures, capturing the ordinary daily events, celebrations, joys, and tragedies in the villages. Exhibitions of his photographs portray these events for the outside world, so others can appreciate the aboriginal ways of life, he feels.