Large-scale forces such as national peace movements can normally promote harmony at the local level and foster more peaceful communities. The opposite generalization often applies: that wars can promote local strife, which helps build violent societies. Developments last week in New Delhi offer hope that peace in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir may some day be possible, and with it the traditional peacefulness in the villages of Ladakh, a district of the state, might be strengthened.

According to Ravinna Aggarwal’s book Beyond Lines of Control (2004), the village peacefulness found so famously among the Buddhist peoples of Ladakh is constantly threatened by the long-standing hostility and problems within the larger state, which are exacerbated by the international tensions between India and Pakistan. Unsophisticated outsiders often simplify the conflict between the two nations into Hindu India versus Muslim Pakistan. In that view, those two nations focus their animosity on the Kashmir region, which has been divided since partition and independence.

But the fissures in Jammu and Kashmir are far more complex, the problems much deeper, than such a simple view allows. And, the critical issue, the violence in Kashmir deeply affects and disturbs Ladakh, which has its own divisions, hostilities, histories, and desires for peace.

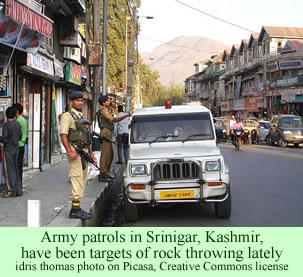

Kashmir has been tortured by violence for the past three months. Young people have been throwing rocks at military patrols, nothing new of course in a state where rioting and killing have been the dominant modes of persuasion by extremists for decades. A peacemaking initiative taken by The Centre, India’s term for its national government in New Delhi, was announced last Wednesday. Mr. P. Chidambaram, Indian Home Minister, informed the press that he had appointed a panel of three peace makers, called “interlocutors,” skilled envoys who would attempt to promote a resolution to the Kashmir dispute. The Indian press was filled with news stories and analyses.

Kashmir has been tortured by violence for the past three months. Young people have been throwing rocks at military patrols, nothing new of course in a state where rioting and killing have been the dominant modes of persuasion by extremists for decades. A peacemaking initiative taken by The Centre, India’s term for its national government in New Delhi, was announced last Wednesday. Mr. P. Chidambaram, Indian Home Minister, informed the press that he had appointed a panel of three peace makers, called “interlocutors,” skilled envoys who would attempt to promote a resolution to the Kashmir dispute. The Indian press was filled with news stories and analyses.

Chidambaram told the reporters that the three members of the panel “are not politicians, but all of them have been in public life; they are well known to the people of India.” He said he expected the three experts to reach out to the young people and the students of Kashmir, Jammu, and Ladakh, especially the youth of Kashmir who have been throwing rocks at the military forces. He said that the appointment of the panel of interlocutors demonstrated the seriousness of the national government for solving the Kashmir issue. He praised his appointees: “We think they are very credible people, people with good track records.”

Many in India had expected the appointment of experienced, senior politicians. The makeup of the new panel surprised the nation. The Home Minister defended his decision and urged that everyone engage with the new group. He expects the panel to interact with people holding a wide range of opinions in the state, and in all three districts. He added that he “would appeal to all sections of people of Jammu and Kashmir and all shades of political opinion to engage with the interlocutors so that we can move forward on the path of finding a solution to the problem.”

Dileep Padgaonkar, a prominent journalist, will be the chief interlocutor. He has worked for the prestigious Times of India newspaper at various senior positions, including as its Paris Correspondent and its Consulting Editor. He was engaged earlier as a peacemaker on a now-defunct committee that studied the Kashmir problem.

The second member of the panel, Radha Kumar, is an experienced mediator and peace scholar. She is the Director of the Nelson Mandela Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution at the Jamia Milia Islamia university in Delhi and the Director of the Delhi Policy Group. She is the author and editor of various reports, such as the “Frameworks for a Kashmir Settlement” (2007 and 2006). She has also authored the books Making Peace with Partition (2005) and Divide and Fall? Bosnia in the Annals of Partition (1997).

Professor M. M. Ansari, the third member of the panel, has been Information Commissioner at the Central Information Commission since 2005. He has written several research and policy studies related to welfare issues. He was the director at the Hamdard University in Pakistan before he was appointed to the post of Information Commissioner for the government of India.

To judge by the press reports, reactions in India have been varied—and perhaps predictable. Syed Ali Geelani, a hard-line separatist leader in Kashmir, dismissed the news. “It is a futile exercise to hoodwink the international community. The step is not going to lead anywhere.” He stated that his own five-point proposal is the only possible basis for a fruitful dialog with the Centre.

Other leaders in Kashmir were not so cynical. Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, the chairman of the moderate faction of the Hurriyat Conference, and Yasin Malik, the leader of the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, indicated they would consider their options before making further comments. Malik said that he did not intend to quickly jump to conclusions.

Ms. Kumar has been engaged in conversations in the past with both Farooq, the moderate, and Geelani, the hard-liner. She recently visited Geelani at a hospital in Kashmir, where he was undergoing medical treatment.

Padgaonkar, the chair of the group, said all the right things immediately after the announcement. He told the Press Trust Of India that his group cannot be expected to come up with immediate solutions, but it will solicit a wide a range of opinions before making any statements. “Our endeavor is to make recommendations which should bring peace and solve the Kashmir issue,” he said.

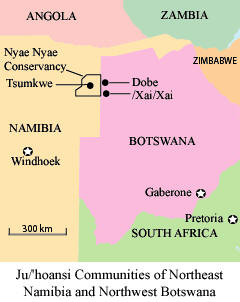

The article concentrates primarily on the Ju/’hoansi of the northwestern corner of Botswana, in the Dobe-/Xai/Xai area, where the members of the Harvard Kalahari Research Group did most of their research, rather than the Nyae Nyae region across the border in Namibia, where the Marshall family expedition had worked even earlier, in the 1950s.

The article concentrates primarily on the Ju/’hoansi of the northwestern corner of Botswana, in the Dobe-/Xai/Xai area, where the members of the Harvard Kalahari Research Group did most of their research, rather than the Nyae Nyae region across the border in Namibia, where the Marshall family expedition had worked even earlier, in the 1950s.

The focus of the three authors is on a Malay chief in the late 19th century named Tok Bayas who lived near the Semai in the Cameron Highlands of Peninsular Malaysia. He accepted his authority from the sultan of Pahang state who derived his power from the British colonial masters. A Semai leader named Bah Busu became friends with the Malay chief, who accepted him as a vassal, a subordinate client.

The focus of the three authors is on a Malay chief in the late 19th century named Tok Bayas who lived near the Semai in the Cameron Highlands of Peninsular Malaysia. He accepted his authority from the sultan of Pahang state who derived his power from the British colonial masters. A Semai leader named Bah Busu became friends with the Malay chief, who accepted him as a vassal, a subordinate client.