Last week, the Tristan da Cunha website revealed that Chief Islander Ian Lavarello, on behalf of the Tristan Island Council, had sent a letter on August 1st to the Norwegian Embassy in London expressing condolences for the mass murders in Norway on July 22.

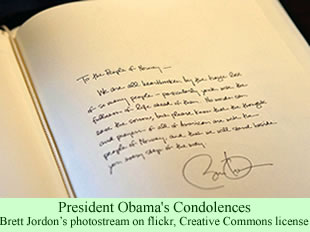

Mr. Lavarello’s letter, portions of which were quoted on the website, echoed the sprit, yet differed in substance, from the message of condolence that President Obama wrote when he visited the Embassy of Norway in Washington four days after the tragedy. The president’s message, hand written in a condolence book in the embassy, was very brief.

Mr. Lavarello’s letter, portions of which were quoted on the website, echoed the sprit, yet differed in substance, from the message of condolence that President Obama wrote when he visited the Embassy of Norway in Washington four days after the tragedy. The president’s message, hand written in a condolence book in the embassy, was very brief.

As reported in the press, he wrote: “We are all heartbroken by the tragic loss of so many people particularly youth with the fullness of life ahead of them. No words can ease the sorrow but please know that the thoughts and prayers of all Americans are with the people of Norway, and that we will stand beside you every step of the way.”

The Norwegians are famed for their peacefulness. The committee that decides on the Nobel Peace Prizes each year is Norwegian, and Oslo hosts the annual Peace Prize award ceremony. The country takes a variety of international peace initiatives. The Oslo Accords of the early 1990s, for instance, which attempted to bring the Palestinians and Israelis to a negotiated settlement, stand out among many examples. The Norwegian people are well known for the peacefulness in their communities.

Mr. Lavarello’s tiny island, with just over 260 citizens, is equally as peaceful, if not so well known. His letter mentioned the historic ties between the Western nation and the obscure South Atlantic island. He recalled the Norwegian scholarly team that visited Tristan in 1938 to study the scientific, social, and cultural make up of the remote place. The scholarship by Peter Munch, who was part of that 1938 Norwegian team, is the basis for including the Tristan Islanders in this website. Munch’s personal journal, published recently, testifies to the quality of the Norwegian scholars—as well as to the independence and integrity of the Islanders.

Mr. Lavarello’s letter described for the ambassador the fact that a museum on the island “helps to tell the story of what is to us, a very special friendship.” He doesn’t mention, in the selection from his letter published on the website, that the special relationship is marked by a common commitment to peacefulness, but it is implied.

Although the text of the extract is nearly four times as long as Mr. Obama’s, Mr. Lavarello expressed his sympathies in equally sincere terms. “Everyone on our island remembers the people of Norway in their hearts and their prayers at this time of great sadness and mourning,” he wrote in part. He may not be a world leader as the American president is, but he obviously has similar qualities of compassion.

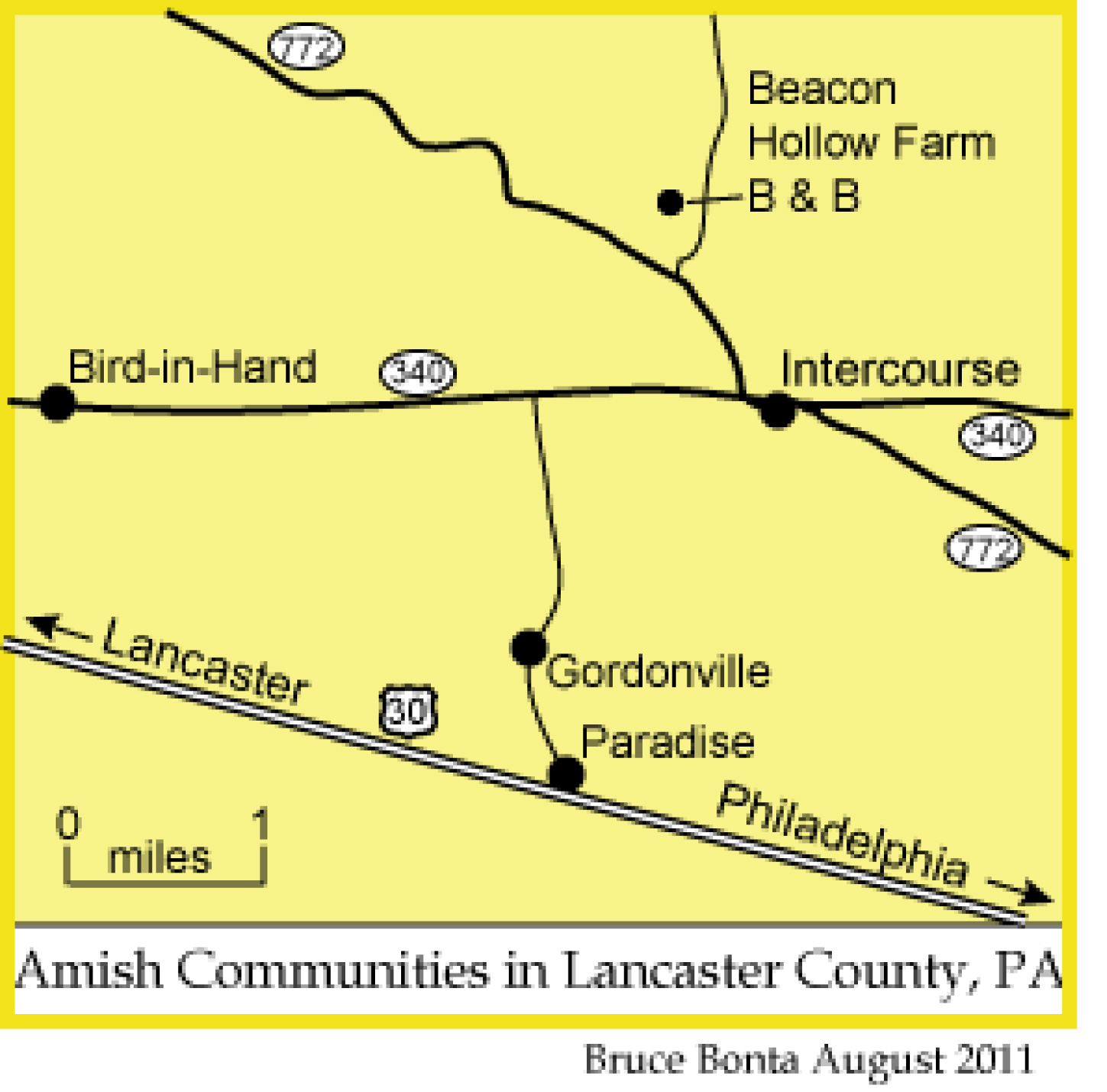

The community, Sungai Ruil, is a couple kilometers off the road from Tanah Rata to Brinchang, about 5 km to the northeast. Tanah Rata is one of the most important tourist centers for the Cameron Highlands resort area.

The community, Sungai Ruil, is a couple kilometers off the road from Tanah Rata to Brinchang, about 5 km to the northeast. Tanah Rata is one of the most important tourist centers for the Cameron Highlands resort area. She did not mention the fascinating history of Forest River. John Hostetler, in his book

She did not mention the fascinating history of Forest River. John Hostetler, in his book