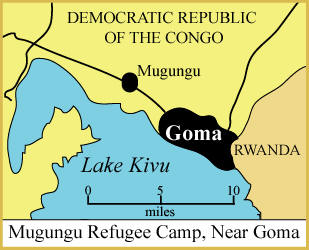

“We are like birds,” said the Mbuti woman. “Today we are here, but tomorrow we will move again. Even when someone dies, we have trouble finding a place to bury him.” Ragi Ngenderezi Abulengu was speaking about her life in the Mugunga Refugee camp, on the outskirts of the city of Goma, in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A news report last week from IRIN, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, quoted Ms. Abulengu extensively about the deplorable conditions in the refugee camp. A similar news story from IRIN last September described conditions in another Mbuti refugee camp near Goma.

A news report last week from IRIN, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, quoted Ms. Abulengu extensively about the deplorable conditions in the refugee camp. A similar news story from IRIN last September described conditions in another Mbuti refugee camp near Goma.

Most of the report last week consisted of a direct quote by Ms. Abulengu. She describes the way the various armies fighting in the eastern part of the country have murdered and butchered innocent civilians, particularly the Mbuti. “When they [meaning soldiers] saw children, the militias simply mutilated them,” she reported.

Conditions in the refugee camp are not much better than the forests where they used to live. If someone does not want the Mbuti to stay in one spot too long, they tell the people to move away. Recently, she says, the city turned off the water supply to the camp. She doesn’t mince her words. “And even eating every day is difficult. We live by depending on other people who were living here before. We work for them and they give us a small amount to eat. Like slaves.”

She says that since the Mbuti are not allowed to own land, they have no way to go back where they came from. Some of her people were removed from the Virunga National Park, she says, and sent to the refugee camp. They were supposed to receive compensation, but they have been given nothing. She describes graphically the discrimination they suffer from the other Congolese.

“When we try to go to the park, we are beaten by the security guards,” she says. “They tell us we are dirty; some use their weapons against us. The last time one of us went there, his shirt was torn by the guards. How can we find our own medicines if the park is closed to us?” She says that the health centers refuse them treatments because they can’t pay for it. They tell the Mbuti, she says, “‘You are a pygmy – get out.’”

Ms. Abulengu asserts that the Mbuti have a lot of potential, but they have no access to services. Whenever they try to secure something, the majority people repress them some more.

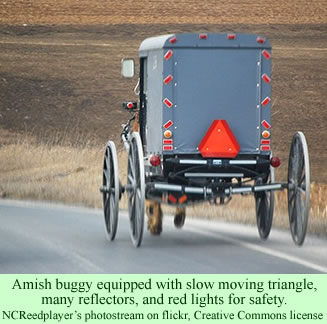

The orchestra launched its “The OSV at My School” program

The orchestra launched its “The OSV at My School” program

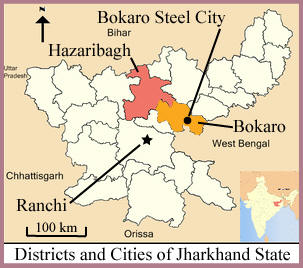

In Hazaribagh district, Kishun Birhor, a laborer working at an illegal stone quarry,

In Hazaribagh district, Kishun Birhor, a laborer working at an illegal stone quarry,

It is not clear from the literature if one of their neighboring societies, the Kadar, have a similar attitude. If so, the prohibition is clearly disintegrating. One of India’s leading newspapers,

It is not clear from the literature if one of their neighboring societies, the Kadar, have a similar attitude. If so, the prohibition is clearly disintegrating. One of India’s leading newspapers,