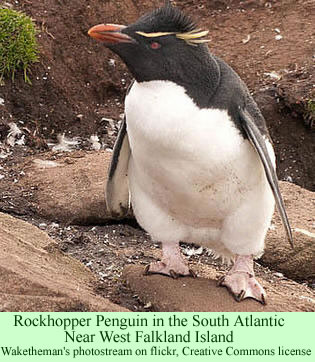

The wreck of a bulk cargo ship, which ran aground on a small island near Tristan da Cunha two weeks ago, threatens the incredibly abundant bird life, the neighboring islands, and perhaps the economy of the people who live on Tristan. About 20,000 endangered Rockhopper Penguins are believed to be covered with oil.

The story at first was picked up by the Tristan Times, but soon the world’s major news media, such as the New York Times and AFP posted articles as well. The best coverage, an hour by hour account with scores of dramatic photos, is provided by the Tristan da Cunha website.

The story at first was picked up by the Tristan Times, but soon the world’s major news media, such as the New York Times and AFP posted articles as well. The best coverage, an hour by hour account with scores of dramatic photos, is provided by the Tristan da Cunha website.

The MS Oliva, a 738 foot long, 75,000 ton ship carrying a load of soy beans from Santos, Brazil, to Singapore, sailed straight into a rocky promontory of Nightingale Island at 7:00 AM on Wednesday, March 16. It is unclear why. A fishing vessel used by the lobster fishing industry on nearby Tristan, the MV Edinburgh, immediately went to the scene. A passenger liner, the MS Prince Albert, was also nearby and responded.

Zodiacs from the Prince Albert were able to get in under the stricken ship’s pilot ladder and rescue the sailors. Fifteen of the 22 crew members were taken by the Edinburgh to Tristan, while the others stayed on the scene in the rescue vessels. The fifteen sailors remain in Tristan for the time being where, in the words of the website, they can “enjoy the legendary hospitality of Islanders who have rescued and cared for shipwrecked mariners for nearly two centuries.”

The Oliva remained intact for a day until it started to break apart on the reef. It began leaking bunker fuel, the diesel oil that powers ships, and some heavy crude oil. Reports vary, but it appears as if the ship carried 1600 tons of bunker fuel and about 1500 tons of heavy crude oil.

Nightingale, 19 miles southwest of Tristan itself, is about one mile across, less than one-thirtieth the area of the main island. Nightingale and the nearby Inaccessible Island, plus other islets, are the breeding grounds for, literally, millions of sea birds. There are no mammals on these islands.

Late summer in the South Atlantic is an essential period for the sea birds, which need to fish constantly for their growing chicks. Oil from the Oliva quickly surrounded Nightingale, its nearby islets, and Inaccessible Island. The oil is fouling the penguins and other bird species as they fish in the waters. A conservation team from Tristan has been working hard to clean oiled birds as best they can. The Tristan website includes many heartbreaking pictures of oiled seabirds and the efforts of their would-be rescuers.

The huge quantity of soy beans which may end up on the seabed—60,000 tons—may have a serious effect on the long-term health of the lobster industry in the area, on which the entire economy of Tristan depends. A more immediate concern is that rats might have escaped from the sinking ship. The shipping company denies that there were any rats aboard, but the conservation team from Tristan quickly began setting out baited rodent traps near the wreck. If a rat population were to become established on the island, the tragedy would be far greater than tens of thousands of killed birds.

None of the news reports mentions the fact that humans—the people living on Tristan—have been sailing their longboats to Nightingale for nearly 200 years to exploit the natural resources there. Peter Munch (1971), in his wonderful book Crisis in Utopia: The Ordeal of Tristan da Cunha, describes in rich, careful detail, the importance to the Islanders of their periodical trips across the sea to Nightingale, which used to be among the social highlights of the year.

Several boats would take the opportunity of good weather to sail across in January to harvest birds’ eggs. Later in the summer they would take young petrels for their fat, and at other times sail to Nightingale for guano. The people depended on those trips for needed supplies. The decision to take the trip caused a virtual holiday on Tristan, with everyone in high spirits, sending off the boats in the morning and welcoming them back a few days later. Whatever the purpose of the trip, the men would also bring back loads of birds to feast on. The whole settlement would be redolent from the smell of wild game cooking each night after the boats returned.

Munch also describes (p.271-281) the tension on the island in 1964 and 1965 when the island administrator tried to reform the people of their long-standing tradition of sailing to Nightingale Island when conditions were ripe. They needed to forget their old ways and accept the fact that they were now part of the Economic System, dependent on wages from their labor at the new fishing factory. The English administrator needed a reliable work force that wouldn’t drop their tools on a nice day and walk off for something as peripheral as a trip to an island 19 miles away. The fact that those trips were an essential part of their culture was immaterial.

But trying to reform the Islanders of their tradition proved to be too much of a challenge for him. After many delays in February 1965, the Islanders finally dropped their tools and left on their boats. Threats to fire absent workers proved to be empty—the administrator would have had to fire virtually the entire workforce on the island. The Islanders achieved their point: that their traditional subsistence economic activities were still essential to their culture.

As Munch concludes his chapter (p.281), the “Tristan Islanders had, in their own quiet way, met the challenge not by rejecting the values of affluence and progress but by putting them in second place to independence, individual integrity, and selective reciprocity based on personal relations.”

The Tristan website, in a section separate from the news about the maritime disaster, indicates that Nightingale Island is still an important source for penguin guano, used as fertilizer for potatoes on Tristan and gathered in January or February. It also supplies penguin or shearwater eggs. The Islanders still hunt young shearwaters in May to collect their fat.

The website does not mention if the island administrators still cause any problems with these trips. Presumably they have long since made their peace over the issue. Of course it is too soon to know if the Islanders will be able to take any more hunting or collecting trips this year.