Summer vacation in the United States is a good time to reflect on the ways schools help strengthen and perpetuate the languages, cultures, and values of a society—as well as teach children necessary skills. News about this topic last week was troubling. The leaders of Nunavut want their school children to learn both English and their own Inuit languages, but there are problems with finding enough qualified teachers to handle the instruction.

The territory established a goal in 2009 to provide bilingual instruction for all children from kindergarten through grade three. However, schools in some communities have not reached that level. Eva Aariak, the Premier of Nunavut who also serves as education minister, told CBC news last week that the government is encountering problems recruiting teachers who are able to handle both languages.

The territory established a goal in 2009 to provide bilingual instruction for all children from kindergarten through grade three. However, schools in some communities have not reached that level. Eva Aariak, the Premier of Nunavut who also serves as education minister, told CBC news last week that the government is encountering problems recruiting teachers who are able to handle both languages.

The difficulty evidently occurs in the High Arctic and Kitikmeot regions, where the Inuinnaqtun dialect of Inuktitut is spoken. The number of speakers of the dialect has diminished, making it hard to find teachers who are fluent in that language.

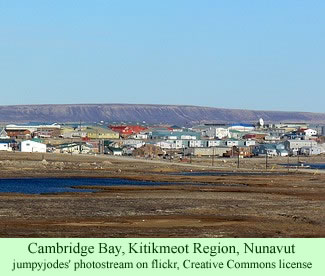

The Canadian national government recognized Inuinnaqtun as an official language in Nunavut, along with Inuktitut, on June 11, 2009. Inuinnaqtun is spoken in the communities of Cambridge Bay and Kugluktut, in the Kitikmeot Region, the western section of Nunavut.

Aariak is hopeful that, as the territory is able to teach more young people to speak their native languages, the problem of having enough bilingual teachers will diminish. But more resources, as well as more teachers, are needed, she insists.

“In order to fully comply with the Education Act today, we would need many more teachers and many more resources,” Aariak told the CBC. The territory has developed a program that, the official hopes, will provide more bilingual teachers for 10 Nunavut communities starting this year.