“The python is considered a good snake and a source of energy for the Orang Asli,” according to Achom Luji, a Semai man from Kuala Lipis in Malaysia.

Last week, the 63-year old man shared numerous stories about snakes and the ways the Semai think about them with a reporter from the New Straits Times. He said that snakes used to serve as guniks, spirits that could be summoned by shamans to help out in various types of ceremonies. Earlier writings about the Semai provide additional information about that statement.

A 1986 journal article by Clayton Robarchek indicates that the Semai considered guniks to be benevolent, protective spirits that help people in times of danger, in contrast with the mara’, malevolent spirits that surround and threaten them.

Robarchek argued that the Semai believe the guniks, in fact, were powerful kinsmen that could be of considerable help when illnesses threaten people. Furthermore, any discord in a Semai village could seriously offend the protective guniks, so much so that they might leave the people, or perhaps even become mara’ and attack them. The belief in the guniks thus help the people retain their peacefulness. It is interesting to learn that the Semai associate their protective guniks with snakes.

The reporter for the English language Malaysian newspaper included the comments by Achom Luji in a piece published on Sunday, February 10. The article was a way of celebrating the Chinese New Year and the beginning of the Year of the Snake. The NST story focused on snake beliefs among the various ethnic groups of Malaysia—the Malays, the Chinese, the Indians, and the Orang Asli—specifically the Semai.

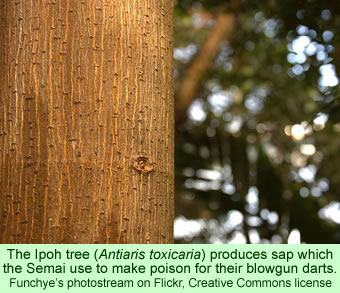

Achom Luji repeated one Semai belief, that pythons were kings in their previous lives, when they were venomous. But due to their doing wrong things, they lost their venom and were made to live in trees. Their venom was taken from them and put into Ipoh trees, he said, which produce the poison the Semai use on the darts in their blowpipes.

The Semai man related a story from their folklore about relationships among the snakes themselves. Evidently, king cobras and pythons used to be friends. But one day a young woman encountered a python while she was approaching some fruit that had fallen from a tree. She was afraid to pick it up.

However, the snake assured her it was a reincarnation of a man who was once fond of her, so the two got married. But then, the man introduced his sister-in-law to a friend of his, king cobra. The sister-in-law violated some rules so the cobra killed her. From that day on, pythons and king cobras have been enemies.

Achom Luji said that the Semai think that snakes represent the reincarnations of human beings. “We believe that all living things were once human. But because of karma, they are reborn as something else. The same goes for snakes,” he said.

The Semai also used to believe, he told the NST, that pythons would go up into the hills above villages to meditate, but when they did that, they might be transformed into dragons. If that happened, the dragons might create lakes around themselves to keep people away. “Sometimes, when there is a landslide, some of us believe that it is because the snake has left its meditation spot,” he added.

He said that, until the 1950s, Semai women used paste to paint the features of pythons on their faces, which symbolized the special values they placed on the snakes. To this day, when Semai artisans make pandanus mats, they sometimes use snakes as motifs.

The NST report suggests that the Semai formerly used snakes for medicinal and cultural purposes. A block of wood in the shape of a snake could be used to help remove bad spirits, or snake venom, from people. In addition, the Semai could retrieve fat from the body of the snake and make medicinal oils.