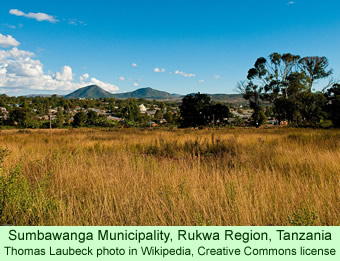

Stella Manyanya, the Regional Commissioner for Tanzania’s Rukwa Region, made a special plea last week for reducing the number of deaths of pregnant women. She issued her appeal to regional leaders at a meeting in the city of Sumbawanga, the historic center of the Fipa people—who traditionally had interesting ways of advancing the health of women.

According to a news report on Tuesday last week, Ms. Manyanya said at the meeting, “it is very unfortunate that as we sit here today, a pregnant woman and a child are dying due to preventable diseases. We have to ensure that such deaths are controlled.”

According to a news report on Tuesday last week, Ms. Manyanya said at the meeting, “it is very unfortunate that as we sit here today, a pregnant woman and a child are dying due to preventable diseases. We have to ensure that such deaths are controlled.”

Dr. Emanuel Mtika, the Acting Regional Medical Officer, said that 55 women had died due to complications during their pregnancies last year, and in the first quarter of this year the figures were even worse: 26 deaths were recorded for just three months. He attributed the deaths to a variety of causes, such as obstructed labor, malaria, sepsis, and excessive bleeding.

The doctor indicated that the regional government has formulated plans for addressing the problem, with a goal of lowering the rate of maternal deaths from the present 138 per 100,000 live births to 90 per 100,000 by next year. He discussed improvements to medical delivery services and the construction of more health centers and dispensaries as appropriate approaches for the regional government to take.

Dr. Mtika also said that 473 children under five years of age had died in the region last year due to such causes as pneumonia, anemia, and malaria. He said the government has set a goal of reducing the infant mortality rate from the present 3.3 per 1,000 children to two per 1,000 by 2015.

“The government is keen to ensure that more lives are saved through improved health delivery and construction of health facilities including dispensaries in rural areas where most Tanzanians live,” he concluded. A newspaper editorial about the development praised the speech by Ms. Manyanya as “a brilliant, highly commendable move by the regional leader who is also a political luminary.”

The traditional Fipa people, of course, had nothing that would compare with the advances of modern medicine, but their approaches to promoting the health of pregnant women are revealing nonetheless. Willis (1980) wrote that when a pregnant women died, the other women of the community would take out their anger on everyone else.

One of his informants, an elderly man named Rafaeli Ntwenya, told Willis how Fipa women reacted when they were stressed. In the words of the Fipa gentleman, “on the death of a pregnant woman in labor …, all the women of the village run wild: it is as though war has broken out. They tear off their clothes and go naked, painting their faces like soldiers with red cosmetic (inkulo). They run about flourishing their hoes and axes. They seize and kill goats and even cows and plunder the fields… (Willis 1980, p.6).”

Obviously, Fipa women in former times were quite capable of making known their intense frustrations about the lack of effective maternal health care, but it is not clear how they express their anxieties today. While there is little doubt that Dr. Mtika’s approach is more effective than painting faces and killing goats, the traditions that Willis reported were important aspects of the dualistic beliefs of their society.