The San living in the desert of Botswana are still strongly attached to the land, Daniel Koehler wrote last week, a value which they hope their children will embrace. Koehler is one of five grantees chosen from a field of 864 people who applied for a Fulbright-National Geographic Digital Storytelling Fellowship. He is living with the San and writing about his experiences in a series of blog posts.

His project is to prepare a documentary film about the social and cultural adjustments that the San people—the G/wi and the G//ana—are making in New Xade, one of the resettlement camps located near the town of Ghanzi in the Ghanzi District of western Botswana. He is comparing their new lives with their former subsistence lifestyle in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), where now only a few of them are able to subsist. His first four blog posts describe his project and his adventures in Botswana so far.

In the first one, dated October 16, 2014, Koehler introduces himself, his project, and the San people. He spent the early years of his life in Uganda, got an education at Elon University in North Carolina, and has focused on documentary filmmaking as a career. He took an interest in the way the Botswana government removed the San people from the CKGR starting in 1997. During his projected nine-month stay, he intends to prepare a film that will explore how the resettlement has affected the cultural identity of the affected people.

He rejects any romantic image of the San people as helpless victims of government oppression. Those kinds of portrayals “deny the San their agency,” he writes, and they overlook the possible long-term intent of the Botswana government to provide a viable future for its minority citizens. He intends in his film to address such questions as how much the San traditions can be adaptable to the processes of modern life. What identities do the San have for themselves? How do they see their futures? How can government policies support their senses of identity? He intends to produce what he calls a character study film, focusing on the lives of individuals, whom he will observe and interview for the final product.

In his second blog post on November 6, 2014, Koehler describes his long trip to Gaborone and his introductions to some San people in the capital of Botswana. He meets Ketelelo, a San man who attributes his own advancing career to the resettlement of his family in New Xade. He was afforded the opportunity, in the resettlement village, of going to school and he proved to be an apt pupil. He then graduated at the top of his class in the town of Ghanzi, and won a scholarship to a major institution of higher learning in Gaborone.

His future seems promising. “If resettlement hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t be here now,” Ketelelo tells the author. Koehler plans to focus his camera on him in order to allow him to share some of his experiences and thoughts with viewers.

In the third blog post of December 8, Koehler briefly describes filming Ketelelo on his campus, and then his drive across the desert to Ghanzi. There he met Kuela Kiema, a San man who has gotten an education and become a published author. He is working to promote instruction in New Xade in the indigenous languages—G//ana and G/ui (or G/wi)—rather than in Setswana, the nation’s national language.

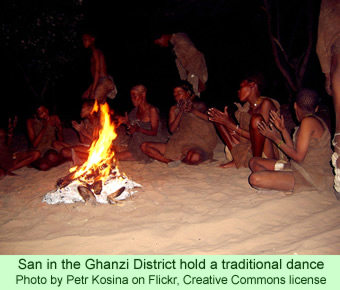

Koehler describes New Xade as a village mixed with traditional and modern living facilities—modern cement buildings and beehive-shaped huts. He quickly got permission from village elders to work on his filming project in the community. He writes that he was attending a traditional dance when he noticed a young man texting on his cell phone. He explains that the nexus of his project is to find out if there is a distinction between the opportunities and the mechanisms of daily life and the deeper issues of cultural identity.

The filmmaker can only upload entries to his blog when he ventures out to larger communities with Internet access, so his fourth post was delayed until last week, January 20. He indicates he plans to write a lot more about New Xade, but he devoted much of his most recent post to a description of a trip into the CKGR, to a small village named Metsiamanong, where a handful of San live without modern facilities—without even running water. These are people who were allowed to return to their former desert homes after the landmark victory of the San in a court case against the government in 2006.

He writes that, unlike New Xade, Metsiamanong has no food shops and no charitable food baskets. The people keep small livestock such as goats, which they supplement with other food sources in order to survive. They use rainwater for drinking and melons for liquid when the water runs dry—as it often does. However, even there, the people are not completely cut off from modernity—they have flashlights, vehicles, and modern clothing.

But more importantly, the San living in the CKGR are firmly connected to the earth they live on, a way of life they wish to continue despite the obvious reality that it is becoming less and less likely. Koehler writes evocatively that they fervently hope their children will be able to “strike a balance” between modernity and tradition, and that the younger generation will wish to go on living in the place of their ancestors.

In Metsiamanong, Koehler met Kitsiso, a young man who moved back to the CKGR to help his father live in the desert. Kitsiso loves the land but he also is pulled by a desire to have a job and to participate in the economy of modern Botswana. He believes that there is more to life than desert subsistence.

Kitsiso’s father is not so ambivalent. “I want my children to live here,” he tells the author. “Every time Kitsiso leaves, I feel a pain. Every time, I wonder if he’s going to come back.”