When she approached the microphone at an international conference in Kuala Lumpur, Fatimah Bah-sin wasn’t intimidated by the fact that she could not speak English. A part-Semai, part Semak Beri woman from a village near Kuantan, Malaysia, she wanted to tell the ASEAN Women’s Forum meeting about the problems she witnessed in her community.

After apologizing to the crowd for the fact that she couldn’t speak English, she asked her audience, as translated by a news report last week, “if indigenous women in other countries face the same problem as I do.” She told the audience that since she has interacted with some NGOs, she has learned a little about the rights of women.

She said she was from a village without good access to information about women’s rights. She had not even known that women had rights. She received a round of applause from the participants when they heard her say, thorough the translation service, “I want to fight for my right[s].”

She spoke with the reporter later and said that she had only received schooling through form three. A mother of five, she indicated that indigenous women in Malaysia were being deprived of their rights to own land. That is contrary to her traditions, she explained, in which women have equal rights to men. “The current system is making it hard for us indigenous women,” she said. She added that women’s lands are being taken without compensation.

The ASEAN Women’s Forum, held on Wednesday morning last week, was one of numerous sessions scheduled for the four day ASEAN People’s Forum conference, April 21 – 24. The overall conference was expected to attract over 1,200 participants.

The newspaper article raises the question of gender relations today in Semai society. Robarchek (1989) observed during his field work among the Semai that their society included a gendered division of labor that was clear but not rigidly applied. They did not have separate ideals for women as opposed to men, and there were no jobs that only women or men would do. He summarized Semai gender relations by writing, “there is no separate cultural ideal of womanhood against which an aggressive ideal of manhood might be cast in structural opposition (p.36).”

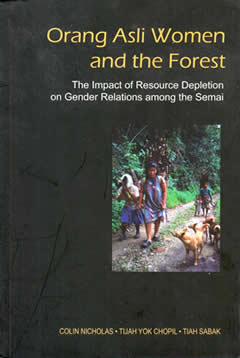

But their society has been changing. Nicholas, Chopil and Sabak (2010) in their book Orang Asli Women and the Forest explore the gender relationships of Semai women and men in the context of social and economic conditions that are quite different today. It is clear from their book that Semai women have their problems with being dominated by the men in their villages. The men often ignore the points of view of the women.

The corollary is that the women frequently tend to accept the idea that they are weaker and of less importance than men, so they often accept domination meekly. Some women accept the premise that the man is the head of the family, and it is his role to make decisions. Semai men appear to believe that they rightfully should have power and authority over women. The men feel that women don’t need to attend meetings—the men should go instead.

The authors advocate the idea that women and men should work together to address issues and make decisions. To some extent, they say, this is starting to happen. Women are getting exposed to some workshops and learning to make positive changes, but in some cases their assertiveness is being condemned by the men.

The newspaper article last Thursday does not mention these three authors, but doubtless they would approve of Fatimah Bah-sin approaching the microphone at the conference and speaking about the land issues in her village. Above and beyond the importance of the land issues she addressed, her courage in overcoming recent trends toward male domination in Semai society is noteworthy.