Every spring and summer, Queen Elizabeth I of England repeatedly ventured out on a “progress,” a series of visits to communities in her realm so she could interact with her subjects. Over the course of her reign, from 1558 to 1603, she visited over 400 hosts, both communities and individual aristocrats who could entertain her in proper style. Building popularity, making public appearances, enjoying lavish ceremonies, and keeping an ear to the ground all motivated the queen and played an important part in the rule of that wise monarch (Cole 2011).

While political rulers today do not need to emulate the queen’s progress—they have many other ways, such as the social media, for keeping up contacts with voters—smart officials still find it is important to directly interact with the people they govern. Rigzin Spalbar, the chief executive of the Leh District in Ladakh, went on a six-day “progress” of sorts last week.

A major news source in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, Scoop News, covered most of his visits to the villages of the Changthang area, the remote mountainous section of southeastern Ladakh bordering on Tibet. While Spalbar may not have worn the jewels and crown of a British monarch, his visits were filled with ceremony, substance, and importance to the local people.

The accounts in Scoop News on April 29 about day two of the tour, on April 30 about day three, on May 1 of day four, and on May 2 of day five are repetitive in some ways—similar issues concern the villagers—but Mr. Spalbar evidently listened carefully. The fascination of the accounts is in the way the whole affair progressed. Mr. Spalbar went from village to village, was welcomed with ceremonies, dedicated new facilities, had public meetings, heard the complaints of the people, took actions, and went on to the next village.

The details provide glimpses into the issues that are important to the rural Ladakhi people. And one thing is clear: it would be a mistake to compare remote, rural Ladakh with 16th century England. The concerns of the people are quite contemporary. Ladakhis in several communities complained, for instance, about the quality of the reception from their local cell phone towers—they do not provide adequate service.

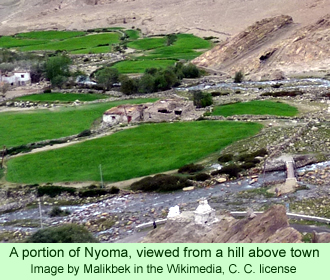

On his second day in Changthang, the Chief Executive Councilor (the news reports refer to Spalbar as the CEC) of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council inaugurated a foot bridge over the Indus River at the village of Kesar. Then, he inaugurated a Veterinary Hospital at Nyoma. Also at Nyoma, he opened an Anganwadi Center, a healthcare facility in the community.

At Chumathang, the villagers articulated their requests: for a residential school, for the paving of a major road, and for the completion of an irrigation channel. Mr. Spalbar responded that the residential school was beyond the bounds of the budget at the present time, but with regards to the other issues, he gave orders on the spot to officers and engineers who were part of his party to immediately look into the grievances of the people. It is clear he wanted progress in the region.

To a request from the people of another village for help in getting a Yak cheese industry started, he replied by instructing one of his officials to begin a training program in the community for starting their business. And do it within one week. The people in various communities complained about their supply of electricity, their lack of a bank branch, their need for a doctor, the need for hand water pumps, the desire for another solar power plant, improvements to rural roads, repairs of bridges, construction of a storage facility for food, new veterinary facilities, and on and on.

For his part, the CEC emphasized in his speeches issues that are of paramount concern to him: education and care for the less privileged members of the community. During the second day of his progress, he congratulated the people of Nyoma for their efforts to improve the quality of education in their schools. The higher secondary school in that community has been achieving significant results, he told his audience, and he urged the people to continue their focus on education.

He evidently emphasized this theme throughout his six-day tour. The children of the Changthang need good educations, which are an important investment so they can get good jobs in an increasingly competitive era. He urged the people to use their earnings from the pashmina trade, and from whatever other sources they may have, to invest in education. In the village of Chushul, on the fourth day of his trip, he repeated his message about the importance of a high quality education for all students.

He also talked about the need for improvement in the care of the elderly and the physically disabled. He inquired about how effectively the government’s old age pensions are providing for elderly people and the physically challenged. In one community, he ordered the District Social Welfare Officer to survey the villages to find out exactly how well the elderly and the physically handicapped are being covered under the appropriate government pension schemes.

The news reports on Mr. Spalbar’s tour certainly give clues as to the progress—and perhaps the lack thereof—of development in the Changthang region of Ladakh.