The Lepchas are confronting the authorities in India’s West Bengal state over their right to have their language taught in the local schools. The controversy, covered in the Indian news media over the past month, echoes the even more serious conflicts of two years ago when the Lepchas sought to dramatize the discrimination they suffered through nonviolent protests—much as they are doing now.

While the conflict this time does not threaten to spill over into violence, it does indicate the seriousness that the Lepchas attach to preserving their culture by including their language in the school curriculum. It also demonstrates the way they cherish the Gandhian approaches to dramatizing their position.

The current conflict began in June 2014 when the state notified officials in its Darjeeling District to begin the process of appointing 46 people to teach Lepcha in 46 different schools in the district. The Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA), a semi-autonomous governmental body in Darjeeling that has some formal administrative responsibilities, decided, however, that it would not proceed in the matter.

The Gorkhas are more numerous—and more aggressive—than the Lepchas in the Darjeeling District. The GTA spokesperson, Roshan Giri, told the district magistrate to not go ahead with the notification process. The agency had decided that it alone had the right to interview and appoint teachers in Darjeeling.

The process continued, however, and by August last year the paraprofessional teachers had been appointed. The GTA filed a case in the state High Court on March 20, 2015, for a stay of the decision, but the court denied it. The matter was further intensified on April 1 when 33 out of the 46 teachers, who had received their appointment letters, were not allowed to enter the primary schools to which they had been assigned.

On April 20 (some sources say on April 17), all 46 teachers, 27 of whom are men and 19 women, launched a dharna, a term used in India for a general sit-down, protest strike. Also on April 20, the High Court further directed the state government to explain why it was having such frequent conflicts with the GTA over issues such as this.

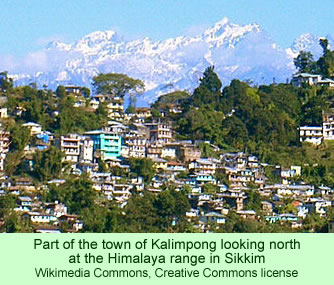

The teachers began their sit-down protest in front of the office of the Sub-Inspector of Schools in Kalimpong, but on May 5 they shifted their action to the more public Triangular Park in the same town. They believed that the change in location would give them more exposure. Robert Lepcha, a leader of the protesters, explained the move by saying that because “the dharna has not been effective so far, we feel it is necessary that it gets [more] public attention.” The dharna had been conducted from dawn to dusk daily, but in its new location, the Lepchas vowed it would be maintained continuously.

Bimal Gurung, the GTA leader, suggested that paraprofessional teachers should be hired to teach the 11 other local languages spoken in the district. Robert Lepcha, asked about that proposal, said he thought it was a fine idea, and his group would support it.

On Monday last week, the Lepchas ratcheted up their pressure on the GTA to formally appoint the 46 people. If the appointments were not made by Thursday last week, they said, they would begin an indefinite hunger strike. Mr. Gurung replied by reiterating his position, that the act that established the GTA gave the power of appointing teachers only to his agency, despite what the High Court had ruled.

Robert Lepcha responded, “Why should anyone oppose us getting jobs? We are all unemployed…. However, our plight doesn’t seem to make any sense to the [GTA] administration.”

It was clear from an earlier news report, in February 2014, that the Lepchas in Sikkim take education very seriously, and the stories over the past month suggest that the ones to the south, in West Bengal state, are similarly committed to having their children at least taught their own language.