Although gender equality has long been a hallmark of the Batek people, the status of women in that society may be starting to fray, according to a report published last week. Patrick Mills, the author of the scholarly report, observes that recent developments, such as the employment of Batek men, may be threatening their traditions.

He provides careful background in his report. He writes that the Malaysian Conservation Alliance for Tigers (MyCAT), organized in 2003 as an association of several Malaysian conservation organizations, recognized that the Batek possess a special knowledge of the forest and of wildlife patterns in them, particularly the habits of the threatened tigers. The group began employing the Batek in tourism activities. MyCAT started what it called “Weekend CAT walks” (“CAT” stands for Citizens Action for Tigers) in the region between the Taman Negara National Park and the central forest reserve.

He provides careful background in his report. He writes that the Malaysian Conservation Alliance for Tigers (MyCAT), organized in 2003 as an association of several Malaysian conservation organizations, recognized that the Batek possess a special knowledge of the forest and of wildlife patterns in them, particularly the habits of the threatened tigers. The group began employing the Batek in tourism activities. MyCAT started what it called “Weekend CAT walks” (“CAT” stands for Citizens Action for Tigers) in the region between the Taman Negara National Park and the central forest reserve.

Volunteer tourists hiked through forested areas along with experts, documenting such signs of tiger activity as nests and pub marks—as well as poaching activities, which the teams would carefully dismantle when they saw them. MyCAT included the Batek as guides for these expeditions.

A Malaysian social organization, FuzeEcoteer, became the organizer of these weekend projects. It employed the Batek as guides in the Weekend CAT Walks. The author, Mr. Mills, who is the Volunteer Coordinator of the project for FuzeEcoteer, focuses his report specifically on the Batek community of Batu Jalang, located on the western border of the national park.

Mills makes many observations about the Batek based on his experiences and his research, but his comments about their knowledge and connections to the forest and the possible deterioration of their gender relationships may be of most interest to those concerned with the peacefulness of that society.

The author points out that the Batek near the national park have become more and more dependent on farming and wage labor, which help separate them from their connections to the forest and threaten their traditional social structure. Most of the jobs have been reserved for men, prompting them to become the primary wage earners in their families, much like the surrounding majority society of Malaysia. As a result, the Batek women have become dependent on men and have taken on more subservient roles in their families.

In a parallel development, Daniel Quilter, the founder of FuzeEcoteer, recognized that the forest knowledge of the Batek made them ideal for conservation work which would help protect the tigers, such as tracking, establishing camera traps, and collecting data. “They have the basic skills to do everything themselves,” Quilter explained. If the Batek had “a bit more focus on things like how to use the GPS and data recording, then we could really start building a good map of animal movements.” Mills writes that further training for the Batek would allow them to gather data such as seasonal changes of populations that would then suggest better conservation strategies.

Employment in these kinds of forest-based activities would not only be helpful for the conservation goals of the organizations, it would also allow an alternative to wage labor and farming. But the critical issue became the fact that the guiding jobs were only being taken by men, even though Batek women have an equal knowledge of the forest.

In order to address this issue, MyCAT and FuzeEcoteer introduced activities that involve Batek women with the volunteer tourists, including leading camping trips and foraging. As a result, the volunteer tourists are gaining a richer knowledge of Batek society, while the Batek are more equally earning income and sharing their knowledge of both their hunting and their gathering. At this point, the effort is still rather small, with only a handful of male guides for the CAT walks, and a group of 6 to 8 women who are leading foraging trips and camping.

Mr. Quilter held a meeting in August 2015 with members of the Batek village in an effort to explore concerns about the program. The Batek welcomed the new forms of employment but some of their elders were concerned about the numbers of outsiders who might come into their village. Too many visitors might lead the Batek to reveal too much of their traditional knowledge.

For his part, Mr. Quilter described his concerns about the lack of sharing among the Batek families of the different opportunities that were being offered to them. The meeting concluded that no more than 10 outsiders per day should be permitted to visit the community, and that the Batek should introduce a rotation system among themselves to better share the benefits of the employment.

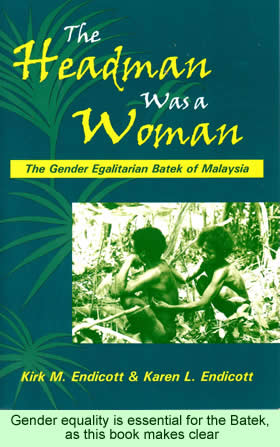

Mr. Mills cites several references at the end of his 1,500 word report, but unfortunately he does not mention the major study of gender equality among the Batek, Endicott and Endicott’s 2008 bookThe Headman Was a Woman. In addition to carefully explaining the importance of equality for men and women in that society, the authors describe the woman who headed a Batek community where they did their fieldwork in the mid-1970s. Named Tanyogn, the head woman energetically advocated for the villagers, effectively confronted rapacious outsiders, and got involved in a hands-on fashion with a range of village projects. The villagers normally followed her lead.

The authors write that the ethical values of the Batek had not really changed when they revisited the community in 1990. One can infer from last week’s report that the concerns Mills expresses about the gender relationships of the people may be a fairly recent phenomenon, based on the introduction of wage labor, and even more recently, the guiding activities.

A news story in August described how Ladakhi women are taking active roles as trekking guides. Mr. Mills’ report implies that the Batek, and their supporters, are striving for comparable forms of gender equality in their own society.