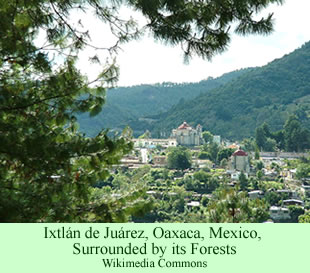

The Zapotec people of one Mexican town, Ixtlán de Juárez, in Oaxaca State, respect each other, work together, and cherish their forests in order to live in peace. Their effective natural resource management strategies and sustainable wood-products industries are based on beliefs that they must treasure healthy community forests.

The Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin has often been cited in the American forest stewardship literature for its long-range commitment to well managed tribal forests. Forest stewards, and those interested in sustainable forestry practices, now have a second indigenous group in North America to emulate. The New York Times featured the Zapotec town last week.

The community evidently takes a long range view of their woods, much as the Menominee do. The reporter quotes Alejandro Vargas, a worker in a pine plantation: “We’re the owners of this land and we have tried to conserve this forest for our children, for our descendants.” Mr. Vargas adds that the reason they feel that way is that they have lived there for many generations.

Ixtlán won the right to own and manage its forests from the Mexican government 30 years ago. Previously, outsiders, under state-controlled corporations, exploited the timber crops without much regard for long-term values. With the community now in charge, the people of Ixtlán have built their own lumber business at the same time they have learned how to care for the land. The town enterprises employ 300 people in logging, caring for the forest, and making wooden furniture.

Ixtlán won the right to own and manage its forests from the Mexican government 30 years ago. Previously, outsiders, under state-controlled corporations, exploited the timber crops without much regard for long-term values. With the community now in charge, the people of Ixtlán have built their own lumber business at the same time they have learned how to care for the land. The town enterprises employ 300 people in logging, caring for the forest, and making wooden furniture.

The Times indicates that the town is now considered to be the gold standard model for community forestry. The Forest Stewardship Council, a highly respected certifying body for sustainable forestry practices worldwide, has certified the Ixtlán forest. That forest is not unique in Mexico, however. Much of the remaining woodland in the country—perhaps 60 to 80 percent—is also owned and managed by communities. David Bray, an authority on community forestry practices at Florida International University, told the paper that the management of forests by communities in Mexico is “astounding.”

The newspaper reviewed the way community lands in Zapotec society are managed by the general assembly of each town, the comuneros, mostly men, who set management policies. These same people also have to commit their time to working in the forest and its enterprises.

Francisco Luna, secretary of the committee that manages the forest and its related businesses, explained the thinking of the people. “You can see the harmony,” he said. “For us to live in peace, we have to respect all the rules.”

The Times reporter asked Pedro Vidal García, a forester who had worked for the community, about problems of illegal logging or other issues related to deforestation. He laughed. The community would judge very harshly anyone who dared to work for, or to guide, a logger who tried to steal trees. That person would be judged severely, branded as a traitor, and lose his own property rights.

The reporter describes the approach of Ixtlán as a unique mixture of socialism and capitalism, although it seems to work. According to Mr. García, it takes a long time for community assemblies, where forest-related issues are discussed, to reach agreements. “The assembly can turn emotional, or technical,” he says. But the forest-related enterprises made a profit last year of U.S.$230,000, 30 percent of which went back into the businesses, 30 percent into forest preservation, and 40 percent to the community and the workers. Those funds support community needs such as pensions, low-interest loans, and support for students living in Oaxaca City getting their educations.

The reporter describes the approach of Ixtlán as a unique mixture of socialism and capitalism, although it seems to work. According to Mr. García, it takes a long time for community assemblies, where forest-related issues are discussed, to reach agreements. “The assembly can turn emotional, or technical,” he says. But the forest-related enterprises made a profit last year of U.S.$230,000, 30 percent of which went back into the businesses, 30 percent into forest preservation, and 40 percent to the community and the workers. Those funds support community needs such as pensions, low-interest loans, and support for students living in Oaxaca City getting their educations.

Alberto Belmonte, a resident who is in charge of marketing the furniture and lumber products, finds the mixture of socialism and capitalism to be odd. It is socialism at the community level, but it includes a commitment to also be profitable, he says. He is trying to open new markets for the furniture the community builds, such as bunk beds for children’s homes.

One worker, Julio García Gómez, returned from a stint as an illegal worker in the United States to employment in the town sawmill. The pay is good enough for him to raise his young family, plus he benefits from the equipment and training. Prof. Bray added that this kind of community forestry will not work everywhere, but in places which produce quality timber, it is a viable management approach. And it is an immense improvement over the previous style of logging.

Francisco Chapela, a Mexican agronomist, suggested that the community forestry plan is working well in Ixtlán. It has created many jobs, brought in a lot of money, and is generally quite successful. Comparing old photographs and recent ones shows a significant improvement in the health of the forested landscape.