Noted peace scholar Bruce D. Bonta, the founder and main author of this website, died on Monday, September 27. He was 80 years old.

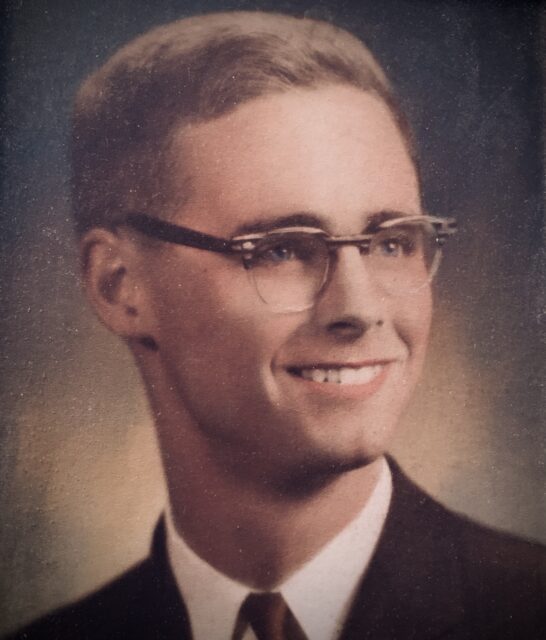

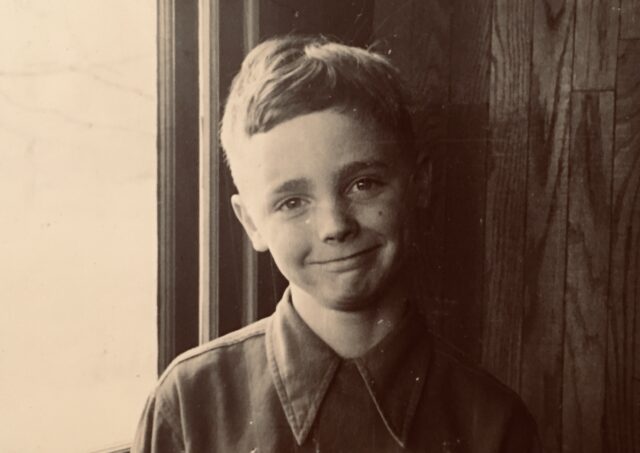

Bruce’s lifelong focus on travel and learning from other cultures began early. He started reading the Christian Science Monitor in 1951 at the age of ten, as part of an otherwise normal childhood in New Jersey. After graduating from Pennington High School in 1959, he attended Bucknell University, and met his future wife, Marcia Myers, when both volunteered to help with Burma-Bucknell Weekend. History majors who shared an interest in the outdoors, their courtship consisted of exploring the back roads of central Pennsylvania on a motor scooter, cementing their love not only for each other but also for the natural beauty of the commonwealth, where both of their families had deep roots.

Bruce and Marcia married in 1962. After Bruce’s graduation in 1963, they headed to Washington, DC, to enroll in the just-formed Peace Corps, but had to drop out when Marcia became pregnant with their first child. Bruce got a job at the Library of Congress, launching him on his career as an academic reference librarian. He pursued his Masters of Library Science at the University of Maine while working at the Colby College Library in Waterville and adapting to country living with his growing family—early participants in the back-to-the-land movement.

In 1971, Bruce accepted a position as reference librarian at Penn State’s Pattee Library, and he and Marcia moved back to central Pennsylvania, this time with three boys and a strong desire to find a place in the woods. They succeeded beyond their wildest dreams, finding an old mountaintop farm in Plummer’s Hollow, on Brush Mountain near Tyrone. Their early years in the hollow were chronicled in Marcia’s first book, Escape to the Mountain. As Marcia’s writing career took off, Bruce became her first and best reader. Starting in the 80s, they relived their courtship on a grander scale, driving all over the state so Marcia could gather material for her “Outbound Journeys” column in Pennsylvania Wildlife, to which Bruce contributed photographs and detailed driving directions essential in the pre-GPS era.

From 1979 to 1991, Bruce gave himself a crash course in environmental law as he and Marcia fought to prevent Plummer’s Hollow from being clear-cut by absentee owners, battling each to a stand-still until the owners agreed to sell. Bruce’s tenacity enabled him to expand the family’s property acreage from 140 to 648. Bruce and Marcia then became active in the Pennsylvania Forest Stewardship Program, where they found many other private landowners receptive to their message of encouraging better deer hunting and trying to learn what the forest itself wants.

During the same period, alarmed by the accelerating extinction crisis and signs of climate change, Bruce and Marcia headed up an International Issues Committee for the Juniata Valley Audubon Society, where they built direct linkages with other grassroots nature clubs in countries like the Philippines, Costa Rica, Honduras, and Peru—a legacy that continues to this day.

The Peruvian connection came about because of a librarian exchange that Bruce set up with a library in Lima, where he and Marcia, with his mother and his son Mark, lived for four months in 1985, traveling at every opportunity to the coastal desert, the Andes, and the Amazon rain forest. Impressed by his Peruvian colleagues’ strongly pro-social culture and how that nurtured a commitment to public service, Bruce co-edited with James Neal a book called The Role of the American Academic Library in International Programs, which led in turn to committee work for the International Federation of Library Associations and many more opportunities to travel abroad—Europe, Australia, and Japan.

The notion that societies can benefit from studying each other led Bruce deep into the anthropological literature. Soon, he began encountering well-documented examples of societies that are mostly if not entirely peaceful and put his research skills to work on a groundbreaking compendium for Scarecrow Press, Peaceful Peoples: An Annotated Bibliography.

So began his second career as an independent peace scholar, which produced several highly cited literature surveys for academic journals and his one-of-a-kind website Peaceful Societies: Alternatives to Violence and War, currently hosted by the anthropology department of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Bruce retired early from Penn State to focus on the site, for which he researched and wrote new articles every week, despite his eventual Parkinson’s disease. And he saw to it that the land he and Marcia had worked so hard to protect would be preserved in perpetuity by donating a conservation easement to Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Bruce is remembered fondly by his family, friends, and colleagues as an exceedingly kind, humble, and generous man. Though he did not practice a religion, he fully lived up to the moral and ethical teachings found in so many of the faith traditions that he assiduously studied. He passed on his values to many around him, and particularly to his children, whom he and Marcia raised without television. In lieu of letting them stare at a screen, Bruce planned and structured family activity nights for listening to classical music, discussing religion, politics, and geography, planning the affairs of the farm, and, through the long winters, reading fiction books aloud. Even when he worked at Penn State, Bruce was always there for his family on nights and weekends, while arising before dawn to commute the hour to State College and arriving home after dark in the winter. He carried a chainsaw and tire chains in the car to remove fallen trees and navigate the often icy, 1.5-mile driveway to and from work, and engaged in numerous projects on the property in his spare time, eventually learning to operate the heavy machinery necessary to keep the driveway open and the trails and field mowed.

Bruce is survived by his wife Marcia, his sons Steven, David, and Mark, granddaughters Eva and Elanor, and great-granddog Obie. A private memorial service is planned for late November. Donations in lieu of flowers may be sent to the Tyrone-Snyder Public Library or Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.