The familiar phrase “no news is good news,” first attributed to King James of England in 1616, certainly has applied to the Ifaluk Islanders over the past few weeks. Does the traditional, peaceful island even exist any longer? The massive earthquake in Japan on Friday, March 11, raised fears of a huge, devastating tsunami for the entire Pacific basin.

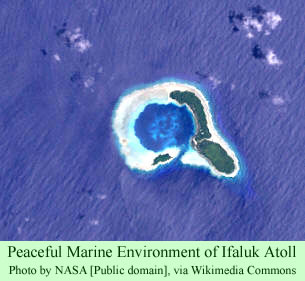

Would it smother out all life on a small atoll in the Federated States of Micronesia, a speck of land where the highest point above sea level is, according to Richard Sosis, only a few meters above sea level—and a bit higher if you climb a palm tree. Ifaluk has two main islands separated by a shallow channel, plus a third much smaller one across a deeper channel. The islands partially surround a crystal lagoon, protected by a ring of coral, where the people do a lot of fishing. They grow crops such as taro root on the slightly higher ground.

Would it smother out all life on a small atoll in the Federated States of Micronesia, a speck of land where the highest point above sea level is, according to Richard Sosis, only a few meters above sea level—and a bit higher if you climb a palm tree. Ifaluk has two main islands separated by a shallow channel, plus a third much smaller one across a deeper channel. The islands partially surround a crystal lagoon, protected by a ring of coral, where the people do a lot of fishing. They grow crops such as taro root on the slightly higher ground.

Global climate change is a real issue on Ifaluk. The increasingly high seas put more salt water into the soil, polluting it and making the cultivation of taro roots, their staple food, difficult. A 30 foot tsunami would drown the island and wash away most life.

The question for the week, at least for this website, was, what had actually happened on Ifaluk? With all the news and horrifying video footage of the earthquake, the tsunami, and the nuclear reactor crisis in Japan, how did the Pacific islands fare? News from the coast of California and Oregon was immediate—the high water caused some damage. Later, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service revealed that the tsunami had destroyed thousands of albatross nests—adults and chicks—on the Midway Islands, an outlier of the Hawaiian Chain and a National Wildlife Refuge.

The first reports out of Yap State—Ifaluk is one of the Outer Islands administered by Yap—in the Federated States of Micronesia were inconclusive. Several missionaries posted stories to their blogs reporting, for instance, how they had alerted other missionaries about the expected tsunami and then fled to the tops of mountains. Jehovah’s Witnesses on Guam reported that all was well with them. Mormon missionaries in Micronesia also reported that they were fine. But they were on the larger islands.

Finally, one of the Mormon blogs included news from Ifaluk. The blog authors, Elder and Sister Sheppard, discuss their reactions when they first heard the news about the coming tsunami. Rush around and warn people; make some phone calls. Leigh—Elder Sheppard—adds more information when he replies, later, to one of the questions posted in the comments section of the blog.

“As far as I have been able to determine, pretty much all of Micronesia was mercifully skipped over by the tsunami. I have seen Doppler displays showing the dispersion of the waves, and we simply were not in the path of the larger swells. We were also blessed by the fact that it was low tide at the time.”

He continues a few paragraphs later, “I have heard no reports from any of our outer-island friends, (and we have lots) or any of the other Micronesian Islands of any problems at all….”

The Mormon missionaries provide better information than a news service called the Pacific Islands Report, the government of the Federated States of Micronesia, or the government of Yap State.

So King James was mostly right. The Ifaluk Islanders were not hit by a tsunami. They presumably continue their conservative, obscure, existence on an isolated atoll, threatened at times by high water but not as yet ready to give up and abandon their island due to rising sea levels.