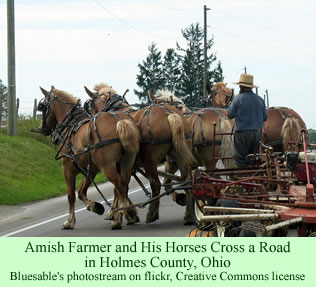

Many Amish people live in Holmes and Wayne counties, Ohio, a peaceful region of rolling farmland normally associated with horses, buggies, bird watchers, and an absence of crime. However, over 150 Amish gathered recently in a barn near Millersburg, the county seat of Holmes County, to learn about the latest criminal craze that has invaded their rural neighborhoods. Meth labs.

Or, correctly, methamphetamine labs. An illegal drug that has taken over other bucolic corners of America, the chemical curse among the corn fields threatens the health and lives of people in rural regions. It is no longer a habit dominated by street corner drug peddlers. Rural people are beginning to take up the production and selling of the substance.

Or, correctly, methamphetamine labs. An illegal drug that has taken over other bucolic corners of America, the chemical curse among the corn fields threatens the health and lives of people in rural regions. It is no longer a habit dominated by street corner drug peddlers. Rural people are beginning to take up the production and selling of the substance.

There is no record, as yet, of any Amish becoming involved, but that is no guarantee that they won’t. A news report last week described in detail the problem of criminals cooking their products and getting other local people involved. It’s a spreading scourge, evidently.

Paul Miller, director of the Amish and Mennonite Heritage Center in Berlin, Ohio, said, “It’s a jolt to the stereotype of the quaint, rural community that we have in Amish country. It’s a jolt to our own values. We don’t condone it. We don’t want to see it happen.” Much as he may not want it, he admits that the problem has arrived.

Holmes and Wayne counties are only a half hour drive from Summit County, where Ohio’s rural meth production began to thrive about 2004. That year, authorities busted 126 meth labs in that county, the highest in the state. Some people still believe that illegal narcotics problems are confined to cities, which have dealt with hard drugs such as crack cocaine for decades. It is difficult to accept that rural areas are becoming similarly infested with such issues.

Over the past year, police have raided eight meth labs in Holmes County, a small figure compared to Summit County, but worrisome since it is much higher than ever before. One meth lab was discovered less than 1,000 feet from an elementary school. The superintendent of that school system decried the situation. “We’re a family-oriented community,” he said. “It shows that these things can crop up anywhere.”

The news story indicates that the reason for the rapid spread of meth in rural areas is that the drug is now quite easy to prepare. Not long ago, dealers had to work for hours preparing their chemicals and cooking the ingredients. Now, the drug is much easier and quicker to make, right in bottles. The dealers prepare the drugs next to their vehicles, then discard the remains into the roadside ditch or nearby cornfield.

Ed Miller, an Amish contractor from Apple Creek, is quite concerned about the development. He participated in the meeting with law enforcement people. “The devil doesn’t care where we live, whether in the city or in the country,” he said to the reporter as he explained his concerns about the rising use of drugs among his neighbors.