Recent hearings conducted by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada prompted shocking testimony about the horrors of the Canadian residential Indian school system.

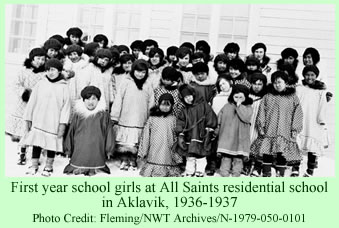

Numerous individuals stepped forward to report on the rampant sexual abuses by the officials, priests, and clergy who ran the residential schools to which the Inuit and Metis children, as well as the First Nations kids, were forcibly sent. Canadian aboriginal children were required to attend these schools since the 19th century. Their purpose was to force the children to forget their native languages and ways and to assimilate into the white majority culture.

Numerous individuals stepped forward to report on the rampant sexual abuses by the officials, priests, and clergy who ran the residential schools to which the Inuit and Metis children, as well as the First Nations kids, were forcibly sent. Canadian aboriginal children were required to attend these schools since the 19th century. Their purpose was to force the children to forget their native languages and ways and to assimilate into the white majority culture.

News stories in Canadian media in recent weeks suggest that the truth and reconciliation process over the past several years may be helping Canada learn about the many abuses that the indigenous children suffered. The youngsters, their children, and their grandchildren continue to experience traumas because of the violence and sexual attacks that some of them experienced at the hands of their teachers. The Canadian government delegated the job of running the schools to the churches, so many of the teachers were Catholic and Protestant clergy.

In June 2008, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper publicly apologized to the Inuit, Metis, and First Nations peoples for the abuses of the residential schools and for the policy of assimilation. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was set up “to put the events of the past behind us so that we can work towards a stronger and healthier future,” in the words of the written agreement between the aboriginal groups and the Canadian government. That agreement provides the mandate of the Commission.

The goals of the Commission, articulated by its Mandate, include provisions for acknowledging the existence of the residential schools, providing culturally appropriate outlets for those who want to describe what happened, and facilitating the beginning of a reconciliation process, both in individual communities and in Canada as a whole. Among its other goals, the Commission is to identify sources of information and to create an accurate record of what happened in those schools.

Over 150,000 indigenous children were removed from their homes and forced to attend boarding schools during the previous 150 years or so. The last school closed in 1996. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission is now about halfway through its task of holding hearings and listening to everyone who wishes to testify. The Commission has received statements from 25,000 survivors of the schools. It has held hearings in about 500 communities, where it has consistently heard tales of graphic physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. It has also heard from about 100 people who worked in the schools.

The Chair of the Commission, Justice Murray Sinclair, explained recently that it is not only the children who attended the schools—and their descendants—who suffer from the experience. People who staffed the schools also suffer. “We’ve had teachers come forward to us and spoken to the commission … about how they so hated the experience of teaching in a residential school that they quickly left,” Sinclair said.

The hearing in Duncan, BC, a few weeks ago added more testimony about the horrors visited on people when a superior society decides to forcibly change, and try to abolish, the cultures of minority groups. “Residential schools were nothing but the rape of our people. They were sexual terrorists,” said Louis Moses Lucas at the hearing in Duncan. He said he always thought of the school as nothing more than a jail. About 250 people attended the hearing, many of whom became quite emotional as the testimonies proceeded.

One woman, herself a victim of abuse, told how she had dedicated her life to reconciliation. On her deathbed, her mother made her promise that she would “be the one that could work [for] forgiveness and love,” the lady said. The graphic testimonies about being raped as children can be read in the Canadian news stories.

Only one Commissioner, Marie Wilson, was present at the hearing in Duncan, but she made it clear that everything was being noted for the record. According to a news story on Friday last week, Ms. Wilson said, “It’s important to know that this is difficult for all of us, not just the speakers and those of us who must officially hear it. As Canadians, we still have so much to learn about what happened.”

The TRC released its interim report in February. It is available as a PDF on the Commission website. The report summarizes the work to date of the Commission, as well as of the Inuit Sub-Commission, which has been detailed to investigate the issues relating to residential schools that the Inuit children were required to attend.