A series of news articles over the past month about the Ju/’hoansi of Namibia provide some interesting new information about the desert dwellers.

Richard Lee, an anthropologist who has studied the Ju/’hoansi extensively, wrote an article picked up by the news aggregating serve allafrica.com about an initiative to foster the bio-cultural rights of the Ju/’hoansi and the other San peoples of southern Africa. Lee explains that the San have enduring values and norms that prescribe how they should manage and relate to the land and its natural resources.

Richard Lee, an anthropologist who has studied the Ju/’hoansi extensively, wrote an article picked up by the news aggregating serve allafrica.com about an initiative to foster the bio-cultural rights of the Ju/’hoansi and the other San peoples of southern Africa. Lee explains that the San have enduring values and norms that prescribe how they should manage and relate to the land and its natural resources.

Bio-cultural rights, Lee explains, are essential elements in preserving the biodiversity that protects the San communities, thus guaranteeing their income, fuel, food security, and, by extension, their self-determination. He describes various workshops and meetings that have sought to build on San values to ensure that the people evaluate contemporary conditions and issues based on their traditional knowledge. A wide range of African organizations are helping out with this work to strengthen the cultures of the San peoples.

On September 4, allafrica.com carried a story by Mathia Haufiku about the changes that are needed for Tsumkwe, the major Ju/’hoansi town in the Nyae Nyae Reserve of Namibia. Likoro Masheshe, the chief control officer of the town of nearly 10,000 people, discussed some developments that are desperately needed in his community.

One of the foremost is the need for a paved road. Tsumkwe is connected to the outside world by a 246 kilometer (153 mile) gravel road, and Masheshe claims that many lives have been lost along it. He is also agitating for the construction of a hospital nearer to Tsumkwe than the present facility, which is 80 km away.

Mr. Masheshe advocates a change in the legal designation of Tsumkwe, from its present status of “settlement” into that of “village”. He argues that such an improvement in the status of Tsumkwe would make the community much more attractive to investors, who should be interested in investing in projects related to tourism in the area.

The article points out that a new solar-diesel hybrid power plant has been installed in Tsumkwe. The community now has continuous electric power without the constant interruptions caused by the older, more inadequate, generators that depended solely on diesel engines. The closest point on the Namibian electric grid to Tsumkwe is 180 km. The old diesel plant could only operate for short periods of time due to the cost of the fuel. The new power plant uses the nearly continuous solar energy, with customers paying only a modest charge to cover the cost of fuel for the backup diesel generation.

Two days later, another news story by Ms. Haufiku reported that the health clinic in Tsumkwe has recently experienced an up-tick in tuberculosis cases. Alisia Okebe, a social worker at the clinic, indicated that, as of the 6th of September, 60 patients were being treated for the disease. She said that the diet of many in Tsumkwe is not very good. Some people subsist on porridge, sugar, oil, and coffee, and basically there is not enough food in the community. “Many people also lack health knowledge so it is difficult to assist them,” she added.

Because of the isolation of Tsumkwe, HIV/AIDS has not become much of a problem yet, but that could change. The health clinic manages a garden project that produces tomatoes, onions, spinach, carrots, and other vegetables, and it runs a soup kitchen that relies on them.

The district coordinator, Johannes Hausiku, indicated that sex education is provided to the inhabitants of Tsumkwe, and officials distribute condoms. But, he complained, he was not sure if people use them. The population keeps growing.

The next day, September 7, a third news story by Ms. Haufiku expanded on the issue of poverty among the Ju/’hoansi in Tsumkwe, undoubtedly the most impoverished community in Namibia. People earn up to N$100 (US$12.00) per month from menial labor.

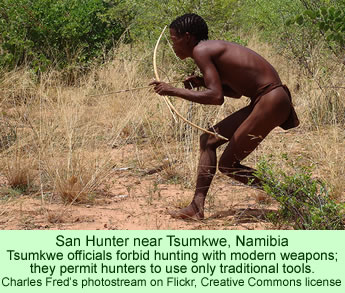

The reporter interviewed Jacob Khankhan, an unemployed man in Tsumkwe. He spoke of how he gets up early every day and chops firewood to earn some money, but he complains that he is not allowed to hunt, primarily, he says, because commercial farms are being develop in the area. He feels that only some of the people in Tsumkwe are benefiting from the Nyae Nyae Conservancy, and more hunting there would help the people, an activity that the Ju/’hoansi have engaged in for millennia.

Another unemployed resident of the community, Wensinslaus Ushuka, said that jobs are just not available in Tsumkwe, so all he can do is rely on government handouts for survival. Sometimes he just sits all day and listens to the radio.

Mr. Hausiku, the district coordinator, responds somewhat defensively. He says that creating jobs in Tsumkwe is difficult because many people are not inclined to attend school. Children only go to school from January to May each year and many leave after grade 10. He also said that the people are permitted to hunt in the conservancy so long as they use traditional hunting tools—bows and arrows—and not modern equipment.

Ms. Haufiku wrote in her final article about Tsumkwe on September 10 that Ellanie Rossouw, manager of the Tsumkwe Country Lodge, a modern tourist facility near the Ju/’hoansi settlement, established in June this year the Cry for Help Day Care Centre for the children of unemployed mothers in Tsumkwe.

She explained that mothers bring their babies from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM every day. The staff provide clothing and food for the children. One of the workers at the new center, Renate Gomes, said that some of the babies are quite ill when they are first brought in, but the day care center is helping them.