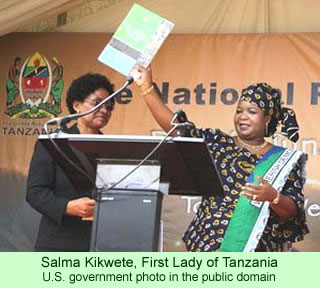

On Wednesday last week, the First Lady of Tanzania, Salma Kikwete, extolled the importance of education to over 1,000 girls at a school in Sumbawanga. The wife of President Jakaya Kikwete said that many young females have been dropping out of school due to pregnancies. She urged girls in the major city of the nation’s Rukwa Region to make other choices.

Ms. Kikwete said that many girls lack support from their parents, and due to poverty and health problems they fail to complete their educations. She said that focusing on studies is more important than engaging in other activities that might be more fun but which might prevent them from achieving their dreams.

Ms. Kikwete said that many girls lack support from their parents, and due to poverty and health problems they fail to complete their educations. She said that focusing on studies is more important than engaging in other activities that might be more fun but which might prevent them from achieving their dreams.

It is not clear if the first lady is aware of the long history of equality for women in Fipa society, the predominant people in the Rukwa Region of southwestern Tanzania. Her comments certainly support that tradition. Roy Willis wrote (1989b), in an article entitled “Power Begins at Home: The Symbolism of Male-Female Commensality in Ufipa,” that Fipa women shared a lot of power and enjoyed much respect and equality in their society.

Willis wrote that 19th century changes in Fipa society made social advancement contingent on peacemaking and socializing skills, both of which were symbolized by the twice-daily meals and frequent sessions of beer-drinking. In both of those activities, adult men and women participated equally, a custom unique among African peoples, according to the anthropologist.

Leisurely meals among the Fipa were, at least when he was in Tanzania, eaten with a great deal of conversation. People would eat and converse without haste, taking food from the central bowls without intruding on their neighbors’ spaces and without appearing to be too eager. If a bowl was out of convenient reach of someone, subtle glances and casual conversation about other topics would be sufficiently strong hints to prompt people to pass the desired food.

People would take balls of dry, but still warm porridge, press their thumbs into them, and using them as spoons, scoop out some of the sauce or relish to quickly but discretely get the food into their mouths. The idea was to avoid getting fingers messy with the sauces, and to have a hand in front of the mouth for the brief moment that the mouth was open. Ceremonial washing of the right hand before and after eating, plus various ritual comments, completed the meal.

Drinking rituals differed from eating, but people were careful when passing bowls of beer around the assembled group from one to the next, since the same principle of avoiding any appearance of greed or selfishness applied as during meals. The critical point was that men and women participated as equals both at meals and during drinking occasions. Even when people became quite inebriated while drinking, Willis wrote, everyone maintained correct forms of courtesy and no one ever became violent. Willis did his field work among the Fipa in the mid-1960s, so social conditions may have changed since then.

Despite the passage of 50 years since the field work by Willis, one can hope that the words of Salma Kikwete will resonate with the girls of the Rukwa Region, and that at least some of them will recall the proud heritage of Fipa women before them.