In early May, the citizens of French Polynesia voted in a new president, an opponent of independence, prompting The Economist last week to weigh in on colonialism in the Pacific region. Tahiti is the most populous member of the Society Islands archipelago, which is the heart of French Polynesia. Throughout the Society Islands, people are generally referred to as “Tahitians” and were characterized, several decades ago, as being quite peaceful.

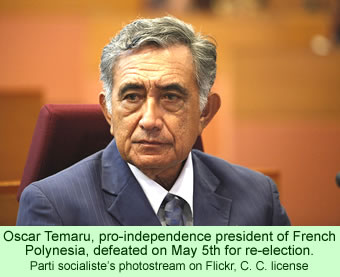

Both major contenders for the position of President of French Polynesia, Gaston Flosse and Oscar Temaru, have occupied the president’s office before. Flosse is dedicated to the territory remaining closely tied to France, while Temaru has been repeatedly elected on a platform of ultimately achieving independence. The voters have elected one and then the other for nearly ten years.

Both major contenders for the position of President of French Polynesia, Gaston Flosse and Oscar Temaru, have occupied the president’s office before. Flosse is dedicated to the territory remaining closely tied to France, while Temaru has been repeatedly elected on a platform of ultimately achieving independence. The voters have elected one and then the other for nearly ten years.

Flosse, the new president, is a controversial 81 year old politician. He is currently at risk of serving time in a French prison for his conviction in January this year on charges of taking 1.2 million euros in bribes from 1993 to 2005. He was also found guilty in February 2013, in a separate case, where he was convicted on charges of embezzling money in a fake jobs scam.

Because of the appeals filed by his lawyers, he was allowed to participate in the election, which he won on May 5. Flosse also serves as a senator in France. His Tahoeraa Huiraatira party won 45 percent of the votes. Critics in France expressed their embarrassment at the outcome of the election. Flosse has often been charged with amassing his fortune by exploiting his political offices.

However, others say that the Polynesians themselves view the French courts simply as institutions associated with white settlers, so they don’t place much stock in court judgments. According to the political analyst Sémir al Wardi in Tahiti, “Gaston Flosse’s appearances in court do not have a significant sway on most voters.”

The UPLD coalition, the pro-independence party of Oscar Temaru, who was the president until being beaten by M. Flosse, won 29.26 percent of the vote on the 5th. A major reason for the defeat of President Temaru has been the declining economy in the territory. French Polynesia, with a population of 270,000, has seen unemployment rise to around 20 to 30 percent. One fifth of the people live in poverty.

Temaru has focused his career on achieving independence for the territory. He first won the presidency of French Polynesia in 2004 based on an independence plank in an election that was mired in controversy for months. Ever since, the office of President has revolved between him, Flosse, and Gaston Tong Sang, another politician.

M. Temaru has appeared to be getting closer to his goal in recent years. The French Polynesia Assembly voted in 2011 to petition the United Nations to have the territory placed on its list of nations that are still colonized. The election results in early May were widely viewed as a result of the economic problems of the territory, rather than as a vote against independence.

In comparison with other independent Pacific nations with comparable populations, however, French Polynesia is not doing too badly. The per capita annual GDP for the territory is almost $20,000, due in large part to financial assistance from France and the still vibrant tourist industry in the Society Islands. Other Pacific nations, by comparison, are not doing so well economically: Fiji has a GDP of $4,800, the Solomon Islands has a per capita GDP of $3,400, Vanuatu is $4,900, and Samoa is $6,200.

The article last Saturday in The Economist gave a different focus to the election results. The magazine pointed out that the United Nations did re-inscribe French Polynesia on the list of “non-self Governing Territories” by a vote on May 17th.

The article analyzes the issues involved with the UN listing by stating that independence is often not the preferred choice of many Pacific islanders. Tokelau narrowly failed to approve, by the required two-thirds majority, an independence referendum from New Zealand in 2006 and 2007. Pitcairn, home to 47 Bounty mutineer descendents, has no desire to achieve independence from Britain. Political leaders of American Samoa have asked that their territory should be removed from the UN list.

The issue in all of these colonies is one of economic survival. France has repeatedly indicated that any territory that votes for independence will lose its generous financial support. New Caledonia, which is rich in minerals, may well have an independence vote sometime in the next few years, a move that was agreed to by a French settler organization and an independence-minded indigenous group. Settler groups there who remain loyal to France hope that compromises can be reached that will allow them to remain under the French umbrella.

But, The Economist indicates, the Motherland might become weary of the whole issue—the costs of maintaining the colonial infrastructure and support systems in the Pacific keep rising. The magazine suggests that Mr. Temaru and the government in Paris may ultimately work out an independence arrangement that will be mutually acceptable.