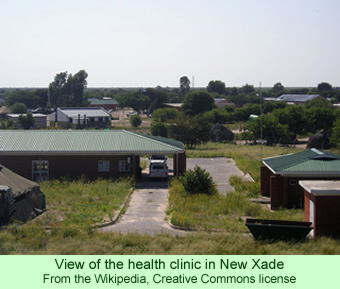

Kesebonye Roy spoke about San life in Molapo, a Kalahari Desert village: “If someone gets sick, we go to the grave site of that person’s ancestor to ask for help.” However, another San person, Mmolawa Belesa, who lives in a resettlement camp called New Xade, located just outside the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), said that he appreciates the health clinic there, where his sick father can get proper care. There are no longer any traditional healers in Molapo, while there are modern health workers in New Xade.

Last week, two South African news services published two different articles about the San people—the G/wi and the G//ana—who were removed by the Botswana government between 1997 and 2002 from their traditional homes in the desert and forcibly required to live in New Xade and two other resettlement camps.

Last week, two South African news services published two different articles about the San people—the G/wi and the G//ana—who were removed by the Botswana government between 1997 and 2002 from their traditional homes in the desert and forcibly required to live in New Xade and two other resettlement camps.

Some San have returned to villages like Molapo in the CKGR, where they live without modern facilities such as running water, while others remain in the resettlement camps. The two reports, one from News24, the other from Independent Online, present a variety of opinions and facts about the two San societies and how the people are adjusting—or not adjusting—to life in the resettlement camp, or to subsistence back in the bush.

Both reports contrast conditions in New Xade—the reasonably modern community of 1,500 people, though beset with problems that the San are not sure how to cope with—and Molapo, the traditional village of 50 people in the bush. They both make it clear that the San people had been living in the resettlement camps for some years before the Botswana Supreme court ruled in 2006 in favor of a suit brought by the San people which allowed at least some of them to return to their ancestral desert homes. The government’s attempt to force the people to adjust to modern life was illegal, the court decided.

Molapo is one of the reestablished communities, a place to which people returned after the 2006 ruling in order to rebuild their lives without modern conveniences. Despite the hardness of life in the desert, the G/wi there have reestablished, at least to some extent, their traditional ways. The residents of Molapo are still able to gather foods in the desert—roots, herbs, and wild berries.

They are not permitted to hunt, however, because the Botswana government has forbidden hunting, at first in the CKGR but more recently throughout the nation. Molapo residents have no source of water other than what they can save from the sparse rainfall and the melons they gather in the bush or grow in their gardens.

Molapo also has a chief, a direct contradiction to their traditional egalitarian social practice, though the incumbent is not recognized as chief by everyone in the village. Molapo and the other desert renewal villages exhibit other contradictions. Jumanda Gakelebone, a noted San leader, argues that hunting by the people, now banned by the government, is an integral aspect of San life.

“The government is trying to turn us into pastoralists, which we are not. We are ecological hunter-gatherers who have a lot to teach the world about how to coexist peacefully with Mother Earth,” he says. But the reporter observes that Molapo residents are already pastoralists: they live with their goats and cattle.

The ambivalence about life in Molapo is expressed by others. Xamme Gaothobogwe argues, “we want the same opportunities as everyone else.” Children must go back to one of the resettlement camps in order to attend school, a fact which Gaothobogwe deplores.

Life in New Xade is different from the bush, but it is not necessarily easy. A few San young people have been able to get educations but, according to Gakelebone, they become ashamed of their heritage. “They even change their names to appear more civilised,” he said. The bar in New Xade fills with customers every afternoon. The attendant at the bar, Kgomotsego Lobelo, says that everyone drinks because “there is nothing else to do.”

Survival International has provided documentation on over 200 cases of abuses of the San people by Botswana government agents, but one of the news reports last week published government statements relating to this issue. A government spokesman denied the allegations made by SI. He indicated that there may have been some instances of abuse, “but most such charges were false,” he stated.

Despite claims that the government has been motivated in its treatment of the minority peoples by its eagerness for royalties from diamond mining, officials deny that argument. The government spokesman said that the hunting restriction in the CKGR was imposed simply to protect the game—it had nothing to do with diamond mining or royalties. The government says that it simply wants to provide modern services to the G/wi and the G//ana people, which it can do best at the resettlement camps.

In New Xade, in addition to the heavily patronized bar and the health clinic, there are some shops and a school. But there are few jobs—most of the residents live on permanent government handouts. It is clear from the two articles that while New Xade provides some services, it also fosters a culture of dependency and cultural degeneration; while Molapo offers some freedom, dignity, and a chance to rebuild a culture of pride, at least for some of the San people, it also provides few of the benefits of modern life.