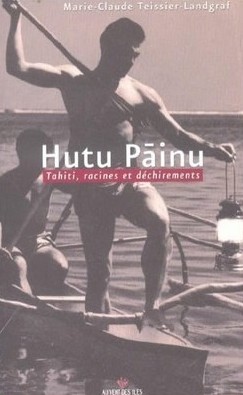

A scholarly analysis of a 2004 French Polynesian novel suggests that there are different ways of understanding the history and culture of the Tahitians, especially in contrast to those of the French colonizers. The scholars, Andrew Cowell and Maureen DeNino, appear to suggest that the novel Hutu Pāinu: Tahiti, Racines et Déchirements by Marie-Claude Teissier-Landgraf may represent, at least broadly, the relationship of Tahitian culture with French colonialism.

The opening of Hutu Pāinu describes the arrival in Tahiti of a young girl, Sophie, with her French mother, Amélie, on a ship from war-torn France immediately after World War II. They have come to Polynesia to be with the girl’s Tahitian father. Contrasts between the cultures of France and of Tahiti quickly become apparent in the different ways the major characters understand humanity.

The opening of Hutu Pāinu describes the arrival in Tahiti of a young girl, Sophie, with her French mother, Amélie, on a ship from war-torn France immediately after World War II. They have come to Polynesia to be with the girl’s Tahitian father. Contrasts between the cultures of France and of Tahiti quickly become apparent in the different ways the major characters understand humanity.

One difference between the Tahitians and the French is in their perceptions of smells, sights, sounds, bodily functions, and sexuality. The novel privileges the sense of smell, the scholars argue. It represents a more Polynesian approach than a French one: the sense of smell has a higher priority to the Tahitians and a lower value to the French, with their more orderly, logical, European way of thinking that places the highest values on sight and sound.

To many Europeans in the 19th century, the sense of smell became associated not only with perfumes and flower gardens, but also with bodily and sexual functions, and beyond that with animals and savages. Smells came to be associated with the lower classes, assaultive and difficult to control, undesirable—threats to the established social and aesthetic order.

But Tahiti was different to the Europeans, who thought of it as a fragrant, floral paradise. The Tahitians themselves place a very high value on the sense of smell, according to the two authors—it is arguably their most highly valued sense. In essence, while there has been a denigration of the sense of smell by Europeans, in French Polynesia, people privilege it.

As Sophie explores the island and grows older, she is frequently confronted with the fragrant and the foul—idyllic lagoons and awful-smelling places in Pape’ete, the capital city. Sophie is only filled with wonder, even at the less than desirable spots: she is not repulsed by them. Her reactions contrast with those of her French mother, who has a strong desire for sanitation. In essence, the character of Sophie suggests a Tahitian openness to sensual experiences, in contrast to the European prudery and control of her mother. Sophie wants to explore the experiences of all the senses and she seems to reject European values.

The neighborhood in Pape’ete where Sophie and her parents settle is filled with unpleasantly loud noises and onslaughts of odors, but Sophie is enthralled by the spectacle, even with those smells and sounds that her mother finds offensive. The vocabulary in the novel suggests the invasive, even the violent, nature of those smells and sounds, but the descriptions also draw attention to the variety and the contrasts. Sophie’s reactions to the sensual onslaughts range from curiosity to wonder and amazement.

But the novel does not really posit clear contradictions. Instead, as a chapter on a July 14th festival shows, boundaries are blurred and distinctions are not crystal clear. Cowell and DeNino write that the July 14th chapter describes a multitude of sensual experiences that echo one another, as they range from delightful to disgusting. The Tahitian senses, at least in this novel, are extremely unstable, ephemeral, and mobile. They merge and confuse, defying any simple categorization or organization. The senses of the festival are highly invasive into the human body.

While Sophie may be delighted by it all, her French mother is tormented. She, and the Catholic school that the girl attends, represent the French social and religious powers in Tahiti that have a hard time dealing with these overwhelming sensations. They attempt to block Sophie’s interests in Tahitian sensory experiences. Every time she transgresses their barriers, they punish her. Her mother would like her to be a proper French girl, but she cannot get her daughter to abandon her interests in the smells of Pape’ete. The girl rejects proper, respectable, odorless French culture and asserts “a positive, Tahitian, olfactory identity (p.123).”

According to the authors, a broader view of the novel is that it examines the utopian view of Tahiti in the Western imagination. Ever since the French captain Baron de Bougainville stopped there in 1768, Europeans have imagined Tahiti as a place where nubile young women swim out to European boats and eagerly offer themselves to sex-starved sailors.

Cowell and DeNino argue that, of all the places that Europeans colonized, Tahiti and French Polynesia became identified with sexual liberty. If the roles of colonizers, in other places, were to suppress violence, ignorance, or disease, in French Polynesia the role of Europeans, especially the French Catholic missionaries and officials, was to suppress sexuality.

The novel makes the contrasts between French civilization and Tahitian culture quite clear. The French feel that the Tahitians should progress from their lower state of civilization to the higher one represented by themselves. They should abandon their more primitive practices, such as bathing naked, speaking in a local dialect, using traditional, indigenous medicines, blowing their noses with their fingers, and dancing provocatively.

Sophie longs, in fact, for the music and dance of the Tahitians, and the smells and touches of people. She associates touch with pleasure, love, and happiness as expressed by a series of contacts with Tahitian women. In contrast, her mother represents denial and harshness.

Sophie’s struggle to be free of her mother’s controlling influence suggests the struggle of women in Tahiti to escape from the domination and definitions made by Frenchmen, such as the successors of Bougainville. The arrival in Tahiti of Sophie, who is of course herself half Tahitian, parodies the arrival 250 years earlier of European discoverers. Like the French, she explores and discovers, but in a non-acquisitive, non-judgmental fashion.

Cowell, Andrew and Maureen DeNino. 2013. “Reading Tahitian Francophone Literature: The Challenge of Scent and Perfume.” International Journal of Francophone Studies 16 (1&2): 113-133