Some Ju/’hoansi families from Tsumkwe, in northeastern Namibia, have been migrating to Grootfontein hoping to find a better life, but all they have found for themselves is suffering. Grootfontein, a town of 27,000 people in northcentral Namibia, is 250 km (150 miles) west of Tsumkwe.

The Namibian, in a story republished by AllAfrica.com, reported on the conditions of the migrants in Grootfontein. The families the reporter, Ndapewoshali Shapwanale, spoke with were clearly disappointed that they had not gotten much if any help from the municipal government. Isaak Kamaseb, a 52-year old man and his family of about 35 people, all moved to the town 20 years ago to escape what he described as harsh conditions back in Tsumkwe.

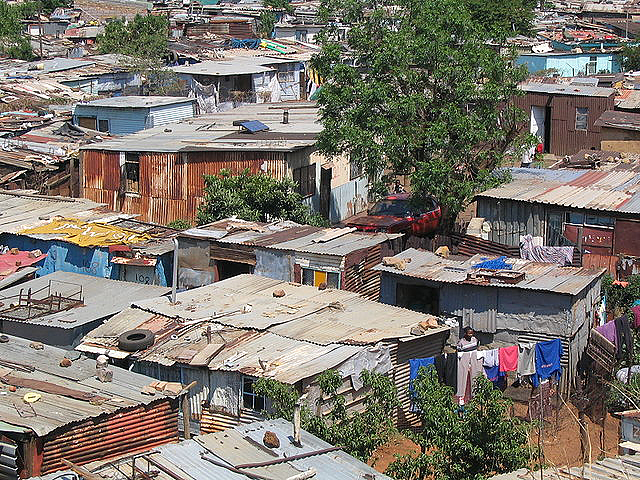

They now live together in a small shack in a poor section of town. Many of the children have never been inside a school. Mr. Kamaseb said that he wanted the children to go to school, which he knew was free, but they did not have enough money to afford to buy uniforms for the kids. He made it clear, while talking with Ms. Shapwanale, that he felt education was quite important but there seemed to be insurmountable issues preventing the youngsters from attending.

Kamaseb indicated that the family does get some drought relief food—the reporter noticed a bucket of maize meal in a cooking area. But a lot of their sustenance comes from scavenging at the town dump, along with other dwellers in the shanty town. Poor people in other communities around Namibia, and in other parts of the world, survive in the same fashion. The women in his home gather empty soft drink and beer bottles from the dump, as does he, and sell them.

Lydia Gaises, a woman in her early 40s, also migrated from Tsumkwe to Grootfontein, hoping to find better living conditions and like him the conditions she found were unbelievable. She visits the rubbish dump, a kilometer from their slum, every day to see what she can find for her family: utensils, clothing, and food. She told the reporter that she hopes her children will not have to face the same conditions she has endured when they grow up.

Ms. Gaises complained bitterly to Ms. Shapwanale, “We have no place to call home. We have no food. We don’t have anything.” Neither of them mentioned the living conditions of other Ju/’hoansi who are still subsisting in villages such as Xaoba around the Nyae Nyae Conservancy, in the Tsumkwe area of Namibia. While they never have plenty, they evidently still can hunt, gather, and raise enough food to get by. Ms. Gaises is grateful that at least they have access to free water in their slum.

A family member of hers, Monica Gaises, complained that health services are hard to obtain and diseases spread easily in the cramped quarters where they are forced to live. Another resident of the slum, Maria Kasmases, added that they really hate to eat discarded foods that they gather at the dump but they have no other choice. The reporter suggested that gathering foods at the municipal dump is similar to the food-gathering in the Kalahari Desert that used to be the norm in their society, but she wisely left it up to the reader to flesh out the comparison.