The Piaroa not only eat giant spiders that they find in the forests of southern Venezuela, they use them for their shamanic purposes. A European TV channel that specializes in culture and arts programing, the Association Relative à la Télévision Européenne (ARTE), sent a crew to Venezuela in order to broadcast last week a program in German featuring the Piaroa and their big tarantulas.

The Goliath bird-eating spider, or Goliath birdeater (Theraphosa blondi), is considered to be the largest arachnid in the world. It inhabits upland forests in northern South America where it lives in burrows and comes out at night to forage. According to an article in the Wikipedia, it is an important part of the cuisine in some communities.

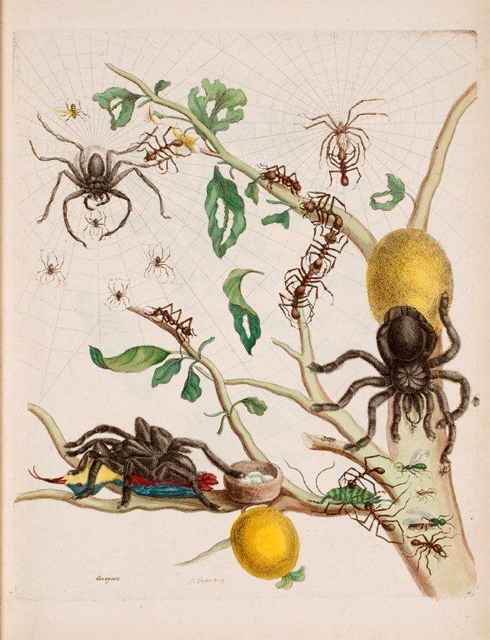

After the hairs have been singed off, it is roasted in banana leaves to bring out the shrimp-like flavor. The beast is so-named because an early naturalist explorer of the region, Maria Sibylla Merian, depicted it in one of her copper engravings as eating a hummingbird.

The ARTE program stated that the huge spiders have always been an important food source for the Piaroa, particularly during the rainy season. During the remainder of the year, the shamans use them to mediate between the living and the dead. However, the conversion of many of the Piaroa to Christianity has diminished the powers of the shamans and correspondingly, the importance of the spiders.

The TV crew in Venezuela went out hunting for the spiders early one morning with a group of Piaroa. Humidity had increased the activity of the animals, which may range up to 30 cm (12 in) across. They live under tree stumps and in small caves underground. Although the spiders are almost blind, they have very sensitive feelers on their feet that tell them where prey might be located. The crew watched a Piaroa spider hunter use the stalk of a liana to make nervous movements in front of a spider’s burrow. The Piaroa was seeking to imitate a possible insect prey and thus to lure the spider out.

Among the group was a man named José, the son of the shaman. José has been trained by his father in all the details of his shamanic practice, and the younger man evidently wants to succeed him. But the spread of Christianity among the Piaroa has been sidelining shamanism, so the video closed with the very valid question as to whether or not José will be able to continue the old ways and beliefs of the people. Or will the Piaroa succumb to the blandishments of modernization?

Shamans, usually older men, have played an important role in Piaroa culture, according to numerous references cited in past news stories. For instance, one reported that the tranquility and harmony of the Piaroa community is based partly on the social values of the people and at least to some extent on the protective work of the shamans. But the role of the bird-eating spiders in their lives is also interesting.

Fortunately, a scholarly article by Melnyk and Bell (1996) provided some good information that amplifies the ARTE story. In their article, the authors described how the Piaroa in a couple villages they studied integrate their horticultural activities with hunting, fishing, and gathering plant products from the surrounding forests. Piaroa who live close to market communities, such as the state capital, Puerto Ayacucho, will sell both their excess agricultural produce and such forest products as fish, plant materials, and arthropods in the town markets. The authors did not specify what species of insects and/or spiders were included in their “arthropods” category.

Melnyk and Bell calculated the monetary value to the Piaroa from a couple villages located near market towns from the sale of their forest products. Table 2 in the article indicated that the annual monetary value that they derived from the sale of hunted and harvested forest foods amounted to nearly US $3,000,000, of which arthropods contributed slightly over US $11,000—less than 1 percent of the total.

The authors concluded that the collection of arthropods in the forests was so small that it represented a “negative return” (p.470) for the people. That is, they reasoned that in economic terms, the people had to invest an extensive amount of time in the harvesting of the arthropods for a very small monetary return. The spiders and insects represented delicacies for the Piaroa, who harvested them regardless of the amount of time they had to use.

Melnyk and Bell admitted that their valuation was only based on comparing forest foods with their prices in the markets. It did not include the cultural and social values of the foods. After all, they reasoned, harvesting forest foods by the Piaroa represented more than just subsistence. “The types of products harvested, the methods of harvesting and the social relationships of harvesting partly define the cultural identity of an ethnic group,” they argued (p.470). The arthropods—the Goliath birdeaters—represent more to the Piaroa than just their sale value, since they are important in sustaining the culture of the people.

A three-minute BBC One video on YouTube shows a group of cute Piaroa children using liana stalks to lure some of the huge tarantulas out of their holes in the forest floor so they can catch, cook, and eat them.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ra4WmE-joMQ