The Pashmina wool sheared from goats in the high plateau region of Southeastern Ladakh has, for centuries, been shipped out to Kashmir, where artisans have fashioned luxurious cashmere sweaters and shawls. Almost all of the profits from this trade have been in the hands of the shippers, merchants, and weavers—everyone other than the Ladakhi themselves. Until last year. A news story last week described the establishment of a path-breaking Ladakhi cooperative that seeks to train women in the villages where the goats are raised to process and weave the goat hair into products that will be sold on the international markets.

G. Prasanna Ramaswamy, the former Deputy Commissioner of Leh, and his wife Abhilasha Bahuguna, developed the idea for the cooperative after a chance encounter he had in the remote village of Chumur, located in the Changthang Region of Southeast Ladakh bordering Tibet. During his visit, he was gifted with a luxurious pair of knit socks by a Changpa woman who was a member of the local Ama Tsogspa, one of the mother’s collectives that have been formed by Ladakhi women. The gift raised a question in his mind—why can’t the women in these remote villages use their innate skills to enhance their livelihoods with this fine wool?

So he and his wife set out to found a weavers’ cooperative. Bahugana said “not only does this initiative [seek] to enhance livelihood opportunities, but [it also fosters] the creation of an identity for a region with its traditional crafts and textiles.” Her husband addressed the broader implications of the new cooperative. He said that by giving employment to the Ladakhi in their own homes, the new venture might help stem the flow of migrants out of the remote villages and into the larger towns like Leh. Prasana added that too much out migration might result in Ladakh losing its unique way of life.

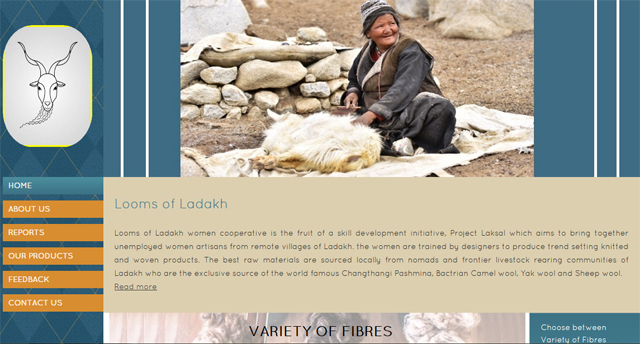

Prasana appointed Dr. Tundup Namgyal to take charge of forming Project Laksal in July 2016, which was intended to form the cooperative itself, to be called “Looms of Ladakh.” Their reasoning was that one Pashmina goat may yield 250 g. of raw wool, one-quarter to one-third of which is enough to fabricate a shawl that could fetch, according to Dr. Namgyal, Rs.15,000 (US$236) on the market. If the women could process the wool and produce the finished shawls themselves, the herding families could retain a lot more of the profits from their goats.

Within a month, the founders began testing a pilot project in Stok and Kharnakling, two villages near Leh, the capital of the Leh Distract of Ladakh. Then, the founders began a training program in those villages and in Chuchot and Phyang, also near Leh. During the following winter of 2016/17, training programs were extended to women in Chushul, Merak, Parma, and Sato, much more remote villages in the Changthang area.

Stanzin Paslmo, an expert on design, conducted the training sessions for 40 of the women in the Leh area. She told the reporter that she focused her sessions at first on the value of the raw Pashmina wool and on the importance of the women’s existing skills. She said she “made them understand the importance of design, size standardisation and finishing.” The village women also came to appreciate the importance of effective branding under the tutelage of Ms. Paslmo, who also designed the logo for the Looms of Ladakh. Their first store with that name opened in the main market district of Leh on May 12, 2017.

The reporter interviewed a woman named Tsering Youdol in Chushul, one of the villages in the Changthang. She said that some members of their cooperative group have 70 to 80 goats and a few have over 100. They take the goats to be sheared and then distribute the wool to their members. “Earlier we weren’t aware of the value of Pashmina,” she said. “At home, it used to lie here and there.” They know better now.

Looms of Ladakh would like to expand the reach of its website and enter the e-commerce sphere, but logistics are a serious issue due to inadequate shipping services in Ladakh. In their first six months of operation, Looms of Ladakh saw their business quickly grow to sales worth Rs 23 lakh (US$362,000), but it might have been more with better planning, according to the reporter.

The news report indicated that the products made by the women are bar-coded and that the individuals earn 37.5 percent of the sales. Out of the sales, 41 percent is kept by the cooperative so they can purchase raw materials for the upcoming season. The remaining funds are used for administrative costs of the organization, utility bills, marketing, skill development, and other expenses. The organization also keeps a percentage to develop a welfare fund for participants to use for health expenses and schooling for their children.