Units of the Philippine armed forces went into a remote Buid village in helicopters on August 16 to provide supplies and support for the villagers, who have no road access to the outside world. The two-day visit to Sitio Mansay, in San Jose’s Monteclaro Barangay, was described in a government publication last week as a response to the threat of terrorism by operatives of the New People’s Army, a communist-inspired terrorist group that apparently is still active in the mountains of Mindoro Island.

The article quoted the commander of the army brigade who has jurisdiction over all of Mindoro, Col. Jose Augusto Villareal. He praised the humanitarian actions of the armed forces, “since what used to be tools of war are now becoming symbols of peace and hope for our people.” He might have added that this should be good news for the peaceful Buid as well as the other traditional Mangyan villagers on the island.

The article goes on to indicate that about 800 Buid registered for government support programs. They also took advantage of free dental services and health programs offered by the visitors. Furthermore, the Buid were given basic training in farming techniques offered by the Department of Agriculture, which gave them farming tools when the training was finished.

However, the military-focused article does not mention any support by the government for schools in the Buid village. Are there any? If there are, who supports them? A curious outsider, reading the Philippine news story, must wonder at the absence of schools from the listing of ways to keep the Buid from embracing the agenda of the terrorists. What better way to reach the Buid than through their youth? For that matter, how do the Buid react to schooling in their villages? The older literature provides better answers than the current government propaganda.

The basic answer from the Buid themselves is that most of them are firmly in favor of learning to read and write so they can better deal with outsiders, but they also recognize the dangers of exposing their children in schools to alien concepts that might undermine their nonviolent values. Remaining aloof from the outside world poses obvious dangers. While this is an issue for most of the peaceful societies, the Buid have shown their unbridled enthusiasm for their schools—and their commitment to maintaining their traditions.

The story in the Hamlet of Danlog, also in Monteclaro Barangay, shows the commitment to schooling as well as the Buid questioning of it. Laki Iwan, a beloved Buid elder, had answers to the questions about how best to educate the children—at least he tried to answer them effectively. He was suffused with a spirit of far-sighted generosity: he had donated the land for several schools for his community during his life, a legacy that the other villagers acknowledged fondly.

He was always known for his generous spirit. One of his 80-some grandchildren and great grandchildren recalled that “he would always give us bananas for food …” He planted gardens just so he could give away the harvests to others. Another grandchild recalled his penchant for always keeping his word. His family said that he frequently exhorted them to study hard for the future of the Buid people.

But founding schools was his special passion. When he realized that a high school he had founded, referred to as Pamana Ka, was growing successfully, he decided it was important to have a document prepared to ensure that his gift of land for the school would not be rescinded by any of his heirs after he died. The administrator of the school, a nun, was impressed, since the idea had not occurred to her. The high school had graduated 10 students from the different Mangyan societies, including the Buid, not long before an accident killed him at age 90. Seven of the graduates planned to go on to college. Three of those college-bound students planned to apply to the new indigenous peoples’ college, Pamulaan, founded by the University of Southeastern Philippines on its campus in Davao City.

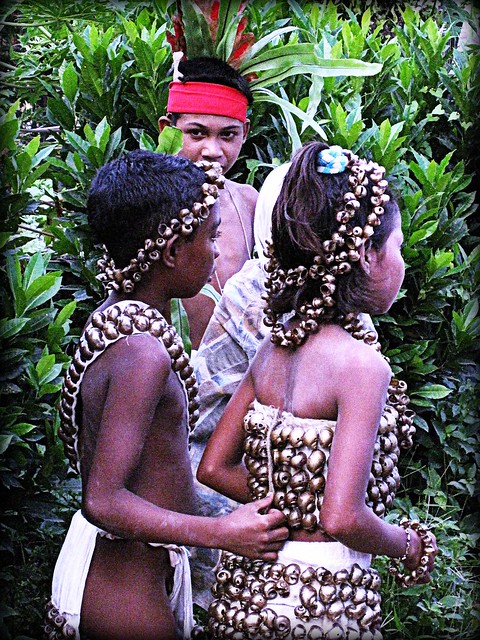

According to an update to the Laki Iwan story two years after his death, one of the schools he helped to found was thriving. It enrolled 48 students from kindergarten to grade three. The teachers used the Buid language in the classrooms to teach their subjects, and the instructors used the traditional alphabet of that society, the surat Buhid, as their mode of teaching. The goals of the traditional school, in the words of the update, were “to promote the protection and preservation of Mangyan culture, and likewise, [to provide] free education to Mangyan children.” The school sought to teach history, math, English, and other modern subjects, but in the context of their own Buid culture and beliefs.

However, some of the traditional Buid people did not easily accept the need for schooling the children. They realized that their youngsters might learn about the works of Shakespeare but remain unfamiliar with their own traditional ambahan poetry, which is preserved in their ancient, written language. Children could attend school and come to see their culture as inferior to that of the West, and Western education as superior to their own ways. Despite the fact that many people have converted to Christianity, the Buid still hold onto many of their traditions.

During a celebration in the school, the Buid recalled how some of their young people had gotten Western educations and then become too good for their traditional communities. Village elders admitted they would be happy when their young people finished college. According to Luisito Malanao, one of the school teachers, while the elders “were happy for some of ours who have finished college courses, they were also disappointed over the influence of modern civilization [on] some of these educated Mangyans that made them abandon the native culture.”

The young people with their diplomas might hesitate to return to their native villages in the mountains due to the mud and the dirty family members. Some hated the thought of sleeping in common rooms in their small houses with the rest of their families. But Mr. Malanao, admitting the disappointment within the Buid communities about the ways some of their children had turned out, concluded that “we cannot afford to stay ignorant and exploited all our lives.”

Another Mangyan schoolteacher, Alma Agular, echoed his sentiments. “We have to embrace basic education without going to schools where we are discriminated [against due to] being Mangyans by lowlanders who dominate these learning institutions,” she said.

Five years later, a major Philippine news source described the Buid schools by focusing on the hopes of Allan Agaw, a 16-year-old student who wanted to give back to his village after he completed his education. He clearly cherished the sharing tradition of his society. “I want to take up engineering so I can help my community,” he said (in English translation). The spirit of giving and sharing, an outstanding characteristic of the Buid, was an essential part of the story of Laki Iwan, of course.

The school in Danlog, which had 10 students in 2006 and 48 in 2008 had grown to 60 by 2013. The reporter found that everyone in the school emphasized the importance of Buid traditional culture. Bapa Ane Arevalo, an elder who taught the ancient Buid script, said, “there are Mangyan[s] who, after studying in the lowlands, come back to the community but don’t speak our language anymore. It’s as if they’re ashamed of being a Mangyan.” Before Pamana Ka was built, young Buid who wanted an education had to study in schools in the lowlands that are part of the majority Filipino culture. Clara Panagsagan, a science teacher, recalled being told, in such a school, that as a Mangyan she knew nothing.

Alma Aguilan, a mathematics teacher, noted that at a lowland school she was laughed at and humiliated because of her inability to correctly pronounce the word “present” the first-time attendance was called. As time went on, even when she knew answers, she still hesitated about participating in classes for fear of having similar experiences. The need for Pamana Ka, a school by and for the indigenous kids, is evident.

Students remain on the Pamana Ka campus most of the year in dormitories, one for the boys, one for the girls, since their homes are so far from the school. The Mangyan students at Pamana Ka raise vegetables and fruits in the fields around the school, and they take care of poultry and fish in a pond on the campus, all of which provide foods that they eat. The staff also live in the community because their home villages are scattered all over the mountains of Mindoro. Margie Munoy Siquico, who formerly taught at Pamana Ka, pointed out that the education of the students doesn’t stop for vacation breaks. She said that all the subjects taught in the school—reading, science, math, Filipino—are infused with Mangyan traditions and cultures because all the teachers themselves are from Mangyan communities.

The Buid elders in Danlog also play an important role in imparting their skills, practices, knowledge, and spiritual values to the students and teachers, especially through the stories they tell. Aristea Bautista, the school director, indicates that the school is committed to restoring “the faith … of the children in indigenous knowledge systems and practices…”

People such as the author of last week’s paean of praise for the Philippine Army might be wise to acknowledge the contributions the Buid make to the idea that schooling can include the nonviolent concepts that are part of the cultures of many nations today as well as their military traditions. Military-minded people have attached celebrations of armies and their accomplishments to many school curricula, but the Buid set an example of focusing an education on a peaceful tradition in addition to the fundamentals of contemporary life.