Five years ago, news stories cited Chewang Norphel for figuring out a smart way to preserve water for Ladakhi farmers, despite increasingly arid climate conditions in their region. The approach developed by the then 74-year old former civil engineer—building artificial glaciers in the high country in order to preserve water into the late spring for the farms below—was innovative for the time and received the support of the government.

In January 2010, over 200 villages in Ladakh were able to take water for springtime farming needs from the artificial glaciers they had built higher in the mountains. For the most effective results, they needed to be built above 4,000 meters in elevation, and they worked best if they were located in shady spots.

But according to an article published last week, the project was soon stopped due to “technical difficulties.” Sonam Wangchuk, another engineer and the founder of the SECMOL Alternative School, decided to address the problems that plagued Norphel’s artificial glaciers. Wangchuk had founded the Students Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) on a campus run entirely on solar and student power.

He observed that Mr. Norphell’s artificial glaciers were often hard for the villagers to reach, and the irrigation ditches built to carry the water down to the farms needed a lot of maintenance. When the ice melted in the spring as temperatures warmed, there was a risk of flooding.

According to a news report last week, Mr. Wangchuk noticed that ice did not melt nearly as rapidly when it was frozen into a conical shape, so less of the surface would be exposed to solar radiation. The artificial glaciers melted rapidly because the entire surface of ice was horizontal, and thus had maximum exposure to the sun.

He calculated that a cone of ice 20 meters wide and 40 meters high would store approximately 16 million liters of water. Wangchuk figured that a glacier two meters thick and storing the same amount of water would have a surface area five times as great as the cone—so it would melt five times faster. The cones of ice that he proposed would allow water to be frozen and stored right where it was going to be used later—near the villages.

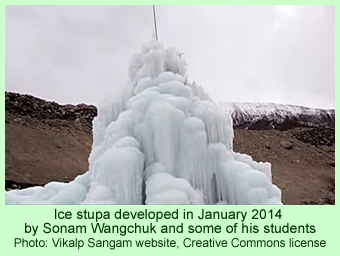

Early in 2014, Wangchuk and some of his students built a 6-meter high prototype ice cone. The process was simple. They brought water down to a barren spot in the village via an underground pipe. With temperatures well below zero Celsius, the water froze quickly as it came out of the pipe (see photo). The first “ice stupa,” as the villagers called it because it resembled a Buddhist monument, lasted in the springtime heat until May 18th, when the temperature finally reached 30 degrees Celsius.

News of the success of the ice stupa spread through neighboring villages. A local Rinpoche blessed the work and hung traditional prayer flags from it. Wangchuk and his supporters founded the Ice Stupa Artificial Glacier Project in October 2014. They plan to erect five large ice stupas in Phyang, a large village with about 2,000 inhabitants, which will store enough water to irrigate 50 hectares of land next spring. Eventually, he says, he hopes to erect 80 large stupas to supply the spring water needs for the entire valley.

Wangchuk might have relied on the traditional Ladakhi means of volunteered village labor (see Pirie 2007, p. 46-48 for a description) to erect the ice stupas. Instead, he and his supporters have launched an Internet crowdfunding appeal on Indiegogo for funds to continue the development of the project.

By November, the team had laid 2.5 km of pipes, overtopped with reinforced concrete. At the present state of development, the water pipes at each stupa have to be manipulated manually, but Wangchuk wants to develop solar-powered machinery to automatically build the ice stupas. Evidently, the Rinpoche has become so committed to the ideas of alternative energy, he is working with another local NGO, Go Green Go Organic, to design a sustainable development project for the Phyang monastery itself.