The Ju/’hoansi are having trouble caring for their dead. According to an article in the New Era, one of Namibia’s major news agencies last week, the mortuaries in Tsumkwe and other nearby communities are more or less dysfunctional. One, located at the Tsumkwe Health Clinic, has not been functioning since 2015. A second mortuary at the police station in Tsumkwe has not been able to store human bodies since August 2017.

The families of the deceased in Tsumkwe, the largest community in Namibia’s Nyae Nyae Conservancy, are faced with transporting bodies to Mangetti Dune, 80 kilometers away, or all the way to the nearest large town, Grootfontein, 250 kilometers to the west. The logistical nightmare is compounded for the grieving family, which has to make the funeral arrangements near the home community and then find a way to bring the body all the way back. Fransina Gauz, the Tsumkwe Constituency Councilor, commented that the only way it works is that everyone helps each other out.

The reporter for the New Era spoke with officials at the mortuaries. All gave plausible excuses for the fact that their facilities were not working: at one, the staff is waiting for a new cylinder of petrol; at another, an official said the mortuary regularly short circuits from rain water leaking into the room. Another mortuary malfunctions due to an internal leakage. The excuses are sad to read.

Samuel Shilikomwenyo, the Acting Otjozondjupa Regional Health Director, said the ministry is aware of the problems—the morgue at the Tsumkwe Health Clinic, for instance, badly needs to be overhauled. But the agency has financial problems that are causing the delays. Similarly, he said that the mortuaries in Gam and Mangetti Dune will be updated when funds become available. He asked people to be patient.

A nurse in Gam explained to the reporter how everyone in the community pitches in when an elderly member of their community dies. “Everyone helps each other. They will always give a helping hand. There was this one time someone passed away. My ambulance driver gave his private car for the corpse to be taken to Mangetti. He just knows the people. I don’t think they’re relatives, but he lent his car for free for the corpse to be taken,” he said.

A nurse at the Mangetti Dune mortuary described the pressures on them when more than one individual has died, sometimes forcing the staff to stack the bodies one on top of the other in chambers large enough for just one corpse. She urged health officials to do more for them. It is not reasonable for the 10,000 people living in the Tsumkwe Constituency to have access to just the one small mortuary at Mangetti Dune.

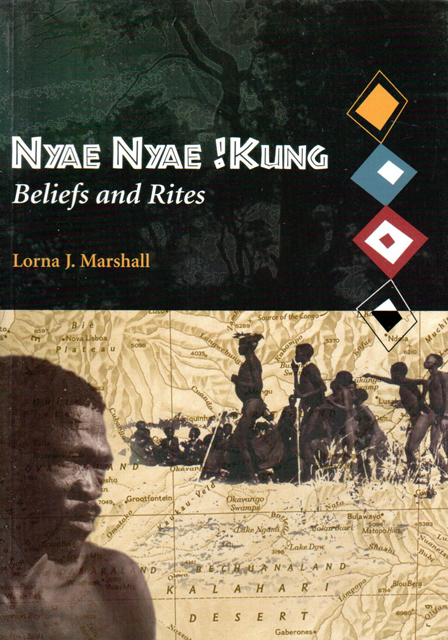

All of this, important and practical as it is, makes the curious reader wonder how the traditional Ju/’hoansi beliefs concerning their dead might fit in. Lorna Marshall, in an article she published in 1962, touched on the religious beliefs of the people, at the time called the “!Kung,” regarding their deceased. (She reprinted her 1962 paper as Chapter 1 in her 1999 book Nyae Nyae !Kung Beliefs and Rites.) Marshall wrote that the spirits of the dead, called //Gauwasi, lived with the great god Gao!na in the eastern sky and came to earth to do his bidding—causing accidents and sickness and in general interfering with the lives of humans.

All of this, important and practical as it is, makes the curious reader wonder how the traditional Ju/’hoansi beliefs concerning their dead might fit in. Lorna Marshall, in an article she published in 1962, touched on the religious beliefs of the people, at the time called the “!Kung,” regarding their deceased. (She reprinted her 1962 paper as Chapter 1 in her 1999 book Nyae Nyae !Kung Beliefs and Rites.) Marshall wrote that the spirits of the dead, called //Gauwasi, lived with the great god Gao!na in the eastern sky and came to earth to do his bidding—causing accidents and sickness and in general interfering with the lives of humans.

Marshall pointed out that the people did not make distinctions between good and bad individuals when they died: they all became //Gauwasi and joined the great god in the east. The Ju/’hoansi were not terrified of the spirits of the dead since the people believed they could be good as well as bad. The news report last week concerns too serious an issue for the reporter to speculate about the possibility that the //Gauwasi are simply interfering with the smooth functioning of the health clinic mortuaries for their own perverse reasons.