Conversations at the local, Central Pennsylvania, Amish farm stand can sometimes be quite revealing—at least to “English” visitors who listen carefully to what the proprietors are saying. A comment last week about a growing family led to the observation by a customer that a recent study from the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown College had provided details about the rapidly growing Amish population.

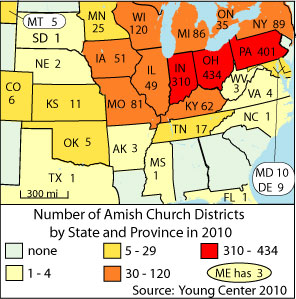

There are now nearly 250,000 Amish people, with new church districts forming in states such as South Dakota, Nebraska, and Colorado where traditional farming is not as easy as it is in Pennsylvania. The visitor did not mention that the new study had prompted a revision to the map of Amish church districts on the Amish page of his Peaceful Societies website. The proprietor would not have access to a computer—she adds up the costs of vegetables with her pencil—so it was better to just listen to her.

There are now nearly 250,000 Amish people, with new church districts forming in states such as South Dakota, Nebraska, and Colorado where traditional farming is not as easy as it is in Pennsylvania. The visitor did not mention that the new study had prompted a revision to the map of Amish church districts on the Amish page of his Peaceful Societies website. The proprietor would not have access to a computer—she adds up the costs of vegetables with her pencil—so it was better to just listen to her.

Her reply was, as usual, quietly revealing. She was already aware that the Amish had expanded into South Dakota and Nebraska. She had read dispatches from both of those states in Die Botschaft. She was too polite to say so, but she clearly didn’t need access to fancy, academic studies—she already knew about population trends because she carefully reads the news.

Many Amish people read their local, daily newspapers. They feel it is important to keep in touch with events that might affect them, and to be at least aware of what is going on in the world. But they also like to keep up with Amish news, the doings in the local church districts in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and the other places where Amish people have settled. Two major weekly newspapers serve that need.

The oldest, and largest, is The Budget, the subject, coincidentally, of an NPR “All Things Considered” story on Friday evening last week. The Budget started in 1890 as a news source for the Amish settlement of north central Ohio, and while it has expanded its coverage to Amish and Mennonite communities worldwide, it still focuses particularly on the Amish of that state.

Subscribers are especially interested in the coverage provided by its “scribes,” contributors from Amish communities everywhere. Visits by relatives from out of state, musings about the weather, stories of births and deaths, accidents on the farm—the kinds of articles that used to be, and in some cases still are, published in small town and rural newspapers around the world. People want to learn what other ordinary folk, not media celebrities, are doing. Small town stuff. In the absence of Facebook, the Amish thrive on it.

The NPR story cites an Amish woman, Mrs. Eli J. Miller in Fredericksburg, Ohio, who wrote in The Budget recently to express her concern about a bird that had perched on her husband’s head while they rested on chairs out on their porch. The bird was pulling out strands of Mr. Miller’s hair, which he found sort of good, but she was concerned that they shouldn’t sit outside so much. The bird might pull out all of his remaining hair. Country humor.

The report says The Budget has 19,000 paid subscribers, who are charged $42 per year to keep up with that sort of news from Amish everywhere. The non-Amish publisher, Keith Rathbun, recently invited its 800 scribes to the home office in Sugarcreek, Ohio, to witness the process of putting their contributions into print. Some of the Amish and Mennonite contributors spoke to the NPR reporter about the sorts of stories they submit to The Budget—a man falls out of a tree and hurts himself—and why that kind of news is significant.

The reporter summarizes the feelings of the readership, 80 percent of whom are Old Order Amish. “For them, the paper is irreplaceable and hyper-local in the days before that became a buzzword in the newspaper industry.” Mr. Rathbun is aware that young Amish are increasingly tied into the world through their cell phones, and he suspects that at some point he might have to make their content available on the Internet. But for the moment, he is committed to publishing the international edition only in paper format, out of respect for his Old Order clientele.

John Hostetler clears up the connection between The Budget and Die Botschaft. He points out that Die Botschaft was started in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1974 as a reaction to some of the stories in The Budget that had been written by people who had left the Amish fold. As Hostetler delicately puts it, a committee of deacons helps to keep Die Botschaft free from the irresponsible thoughts of those who have forsaken the faith of their fathers.

A Los Angeles Times article in 2006 provides a lot of additional details. The LA Times reporter visited Die Botschaft immediately after the tragedy at Nickel Mines, to see how the prominent Lancaster County Amish newspaper would handle the story. Elam Lapp, the editor of the paper, assured the reporter that the upcoming issue of Die Botschaft would not have any news about the shooting. Instead it would carry its usual complement of stories about the corn harvest, an accident with a pitchfork, tame foxes, newborns, and appendectomies.

The following edition, on October 16, might mention the tragedy, but would leave out the gory details. The policy of the newspaper forbids coverage of war, murders, religion, or love. “We might mention that it happened,” said Mr. Lapp, an Old Order Amishman, who edits the paper from his farmhouse. The LA Times article indicated that the paper had, as of 2006, 11,000 subscribers who paid $32 per year, so it was obviously not too much smaller than its much older competitor. It has 600 unpaid scribes who contribute the news stories.

The reporter was obviously impressed with Mr. Lapp, who was deeply affected by the horrifying news of the Nickel Mines tragedy. He said he had quickly deleted a voice mail message to his business phone from his brother, who had personally seen the carnage inside the schoolroom. “I really didn’t want anyone to hear it,” he told the reporter. All the while he spoke with the LA Times, his five year old daughter sat next to him and kept interrupting. He patiently answered her every question, then returned to the reporter.

All of this to explain why the owner of the Amish vegetable stand in Central Pennsylvania subscribes to Die Botschaft to learn about new church districts in South Dakota.