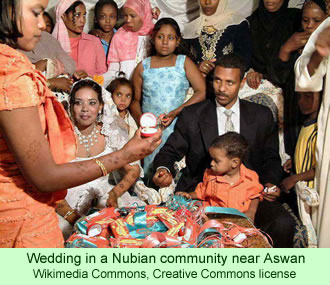

An article published last week argues that the wedding customs of the Nubians living in New Halfa, a resettlement community in Eastern Sudan, are unchanging. The author, Abdalla Hassan Al-Haj, writing an essay for the magazine SudaNow published in Khartoum, which was reprinted in AllAfrica.com, asserts that the Sudanese Nubians are desperately trying to prevent their customs, social traditions, and language from dying out. They cling to their traditional wedding ceremonies as a way of preserving their cultural heritage.

This interpretation differs somewhat from an earlier, more scholarly, analysis of the marriage ceremonies of some Egyptian Nubians living at their resettlement camp to the north of Aswan. That analysis, written by Samiha al-Katsha and published in the book Nubian Ceremonial Life in 1978, describes the elaborate details of the wedding customs, and the ways they have changed, in a resettlement community called Kanuba.

This interpretation differs somewhat from an earlier, more scholarly, analysis of the marriage ceremonies of some Egyptian Nubians living at their resettlement camp to the north of Aswan. That analysis, written by Samiha al-Katsha and published in the book Nubian Ceremonial Life in 1978, describes the elaborate details of the wedding customs, and the ways they have changed, in a resettlement community called Kanuba.

Katsha argues that changes in the wedding customs practiced in the Egyptian resettlement community have occurred due to a secularization process, which opened up a willingness to accept outside stimuli and innovations. And perhaps more directly, the Egyptian Nubian resettlement camp is subject to the process of cultural borrowing. “New ideas were introduced from the cities and upper Egyptian towns, and they were quickly adopted,” Katsha writes (p.202). A news story in 2012 briefly reviewed the Egyptian Nubian customs, though without the detailed analysis that Katsha provides.

Last week’s article offers a useful Sudanese perspective. The author does admit that some changes are, in fact, occurring. Traditionally, the parents of a pre-pubescent boy would choose his bride, the daughter of another member of the extended family. This custom is abating, “as the winds of change [continue] to blow,” Hassan writes.

One of the differences among the various resettlement communities is the ancient Nubian ritual of applying henna as an integral part of the wedding ceremony. In New Halfa, the Sudanese Nubian community, the inner palms of the groom’s hands as well as his feet are painted with henna by his sisters and mother the evening before the wedding ceremony. This henna ritual is performed in the presence of close friends.

At the same time, in her house, female relatives of the bride cover her hands and feet with careful drawings made with henna. Unlike for the groom, the henna ritual for the bride is performed with only women and girls participating.

By 1978, when Katsha was preparing an analysis of the Kanuba wedding customs, the henna ritual was already starting to change. Henna was no longer the primary substance used for beautifying or adorning the bride and groom. Only symbolic touches of the substance were applied to the couple. Evidently, a Kanuba woman who had lived in an urban area substituted for the henna rituals at her own wedding some songs and a procession she had learned about. Weddings since then followed her example.

Brides in Kanuba began preferring to use cosmetics, substances that they felt were more modern and appropriate, instead of the henna. Also, grooms who had to go back to work didn’t want to appear on the job with their hands stained. In the traditional villages, they would not feel embarrassed by the decorations, as they would in mixed groups of Arab and Nubian workers.

Both articles, plus the news report from 2012, emphasize that the wedding ceremonies provide happiness to the Nubian people. In New Halfa, Hassan writes, the gatherings before the wedding ceremony “are meant to express happiness and to tell neighbouring villagers that a happy occasion is [imminent].” While wedding customs were clearly changing in Upper Egypt nearly 40 years ago, they appear to remain fairly traditional in Sudan.

Although Hassan’s article uses the present tense and it appears to be based on the Nubian resettlement community of New Halfa, it also refers, in its conclusion, to participants, at the Nubian weddings, processing to the River Nile, which in fact is over two hundred miles away. So it is not entirely clear how much the piece reflects the prevailing wedding customs at the Sudanese resettlement community and how much it reflects past practices. In any case, wedding ceremonies are still essential elements of Nubian society, however much they may or may not have changed.