The Kadar living in the Anapantham Colony had to move to another location, Sasthanpoovam, nearly 10 years ago when their colony was nearly destroyed by landslides. A mother and a child had been killed in the tragedy. By 2010, they had moved to temporary shelters in the new community and, according to a news report at the beginning of last week, it is now thriving.

Well-maintained roads connect the new colony with the nearest township, the temporary buildings have been replaced by permanent structures, and the Kadar are most appreciative. Reporter Vaisakh E. Hari writes that Kerala government agencies have built 68 houses for the Kadar in Sasthanpoovam, with Rs. 2.50 lakh (US $3,938) from tribal development funds and the same amount from Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group funds.

Well-maintained roads connect the new colony with the nearest township, the temporary buildings have been replaced by permanent structures, and the Kadar are most appreciative. Reporter Vaisakh E. Hari writes that Kerala government agencies have built 68 houses for the Kadar in Sasthanpoovam, with Rs. 2.50 lakh (US $3,938) from tribal development funds and the same amount from Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group funds.

Changes and some modernization struck the reporter during his visit to the new settlement. One person was using a mobile phone with a customized ring tone. The Kadar are integrating outside values while keeping alive their own traditions, the reporter writes. Children are starting to regularly attend tribal schools in the area.

One resident of the colony, Sasi, told Vaisakh Hari that “a huge change [is] visible in the mentality of the residents.” Their contacts with outsiders were quite limited at the former location, but now the people are going into nearby communities for jobs, such as in construction work. “The barrier between them and the outside world is slowly diminishing,” Sasi added.

The use of the traditional Theendarippura, a special building for pregnant women, has lessened, but the Kadar are requesting the construction of a new one anyway, so the government has allocated Rs. 4 lakh (US $6,301) out of Scheduled Tribe funds to build it. And the people continue with their primary trade, collecting non-timber forest products such as honey, which they sell. The reporter indicates that an earlier prohibition on women coming out of their homes to greet visitors has lessened.

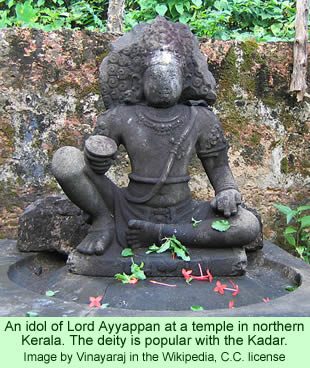

But according to the news report, the Kadar still worship the same two gods, Maladaivangal and Murugan, as they have in the past, and their idols are still commonly seen in the colony. Ethnographies of the Kadar over the years describe different gods. Anantha Krishna Iyer (1909)wrote in a supercilious fashion that “the religion of the Kadar is a rude animism (p.11).” To support his judgment, he described their worship of Kali, especially the preparations by virgin girls for the ceremonies. The Kadar also worship Lord Ayyappan, a major deity of southern India, and Malavizhi, whom he describes as a sylvan god and ruler of the hills.

Another early ethnographer, Edgar Thurston (1909), followed the example of Anantha Krishna Iyer by referring to Kadar religious beliefs as “a crude polytheism (p.21).” He indicated that their practices focused on the worship of gods, most of which were located at special spots in the mountains. He described five such places. For instance, the Kadar worshipped Iyappaswami at a rock located beneath a teak tree. They appealed to that god for protection from sickness and disease.by makinge marks on the stone with ashes.

Hermanns (1955), in his account about Kadar religion, describes a variety of religious practices and the gods they worshipped. Among them, he writes, the chief is Aiyappan (Ayyappan), the first man and ancestor of the Kadar. Ayyappan is a hunter god who assists the Kadar in securing game, protecting them from snakes and wild beasts, and helping save them from various other dangers in the forests.

One elder told Father Hermanns, “‘Aiyappan is our most powerful protector and mountain god. We honor him together with Shiva (p.146).’”