A museum exhibition in Malaysia celebrates some of the major issues facing the Orang Asli societies: managing their interactions with nature, maintaining sustainable lifestyles, and adapting to the challenges of modernity. The exhibit features the photographs of Mahat China, a prominent Semai poet, novelist, and radio announcer. Entitled “Orang Asli and their Traditional Knowledge,” the exhibit is on display at the Kuala Lumpur Performing Arts Centre through Sunday, October 31.

The exhibit was organized by Prof. Hood Salleh of the Institute of Environmental Development at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia and his assistant, photographer Victor Chin. The arts center website indicates that the purpose of the exhibition is to “highlight some facets of the daily life of some of these [Orang Asli] communities.” The aim of the show is to give the people of Malaysia a broader understanding of the ways the Orang Asli, the aboriginal societies of the country, interpret their world and interact with their surrounding natural environments.

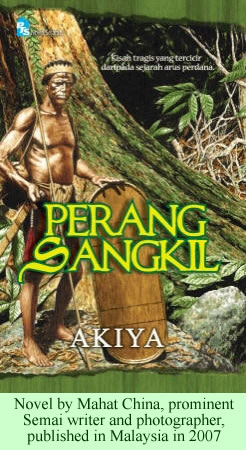

Mahat China, whose nickname is “Akiya,” comes from Kampung Erong, Ladang Ulu Bernam, in Perak state. He has been a published writer and poet for several decades. His eight photographs included in the exhibit focus, he says, on the “beauty tips, simple lifestyle, environmental consciousness, arts and crafts” of the Semai people.

His own website describes his background and his development as a storyteller and advocate for Semai culture. He was the first-born son, in 1953, of a family living in the forests of Perak. As the oldest child in the family, he soon learned about responsibilities for younger siblings and the work involved with survival in an aboriginal community. He worked in rubber fields, collected rattan, and helped around the house. He finally started attending school at the age of 10.

Perhaps most importantly, he listened to the stories of his mother, a traditional, expert Semai storyteller, a cermor, and he later wrote them down. When he went off to secondary school, he was inspired by a teacher to begin writing his own stories. He rebelled against outsiders telling the history of his people and he decided he should tell them himself. He wanted the truth of the aboriginal experience to not come from others—he could write it better, he felt.

He published books of poetry, short stories, and finally a novel, Perang Sangkil, which was published in the Malay language by PTS Fortuna, in Selangor, in 2007. In 1976, he discovered that he also wanted to capture the experiences of the Orang Asli in photographs as well as in his writing. He started collecting photographic equipment and taking pictures, capturing the ordinary daily events, celebrations, joys, and tragedies in the villages. Exhibitions of his photographs portray these events for the outside world, so others can appreciate the aboriginal ways of life, he feels.

He published books of poetry, short stories, and finally a novel, Perang Sangkil, which was published in the Malay language by PTS Fortuna, in Selangor, in 2007. In 1976, he discovered that he also wanted to capture the experiences of the Orang Asli in photographs as well as in his writing. He started collecting photographic equipment and taking pictures, capturing the ordinary daily events, celebrations, joys, and tragedies in the villages. Exhibitions of his photographs portray these events for the outside world, so others can appreciate the aboriginal ways of life, he feels.

He indicates that he is retiring from his job as a radio broadcaster, but he continues to see, as his mission in life, educating “the outside world on the Beauty of his People and in so doing [ensuring] the survival of [their] culture, language, history and traditions.” He told the press that he has invited some Orang Asli musicians to the Kuala Lumpur museum for an afternoon of music on October 31, from noon to 6:00 PM. He indicates that they will be open for discussions with members of the audience who wish to learn more about Orang Asli culture, art, and music.

Other Orang Asli photographers who are featured in the exhibit include Dr. Norhayati Ahmad, a zoologist, her student, Chan Kin Onn, and Victor Chin. Norhayati and Chan exhibit ten photos of Malaysian snakes, toads and frogs. They include information about the herps they picture, such as their coloration patterns and the ways they blend in with their backgrounds.

Summarizing the exhibit, Victor Chin says, “each of the Orang Asli communities has its distinctive understanding of history and customs. … By looking at the way they conduct their lives, we can increase our understanding of their world.” Mahat adds that the works on display show the interconnectedness of human life with the natural world. “Living in harmony with nature, as the Orang Asli do, has important lessons for modern society while the colourful and diverse list of amphibians and reptiles showcases Malaysian bio-diversity which has to be protected and preserved for future generations.”

In a lengthy opinion piece published on Tuesday, Mr. Chin provided further information about the exhibit, the photographs, and Semai society. His sentences about the importance of fear to the Semai are of special interest. He quotes a Semai man named Ronnie, a 32 year old photographer whose pictures are displayed for the first time in this exhibition. Ronnie told Mr. Chin that he tries “to capture a certain Orang Asli look. Especially the look of fear — scared of unfriendly strangers, up to no good, coming into their village. Our history is full of sad stories of outside exploitations of our culture and environment.”

Dentan describes quite effectively the Semai focus on fear in his 1968 book on that society. He argues that they teach their children nonviolence by inculcating in them a fear of aggression equal to their fear of thunderstorms, which they also develop in their children.

Robarchek explains the importance of fear to the Semai in greater detail. In a 1977 article, he argues that they learn in childhood to fear the process of emotional arousal itself, which they see as threatening. Thus, the awakening of frustration is a frightening thing in and of itself. They seem to fear anger of any kind and for any reason, and they vastly exaggerate the consequences of corporal punishment. If a child were spanked, he or she might die, they believe. In fact, the arousal of any kinds of strong emotions promotes fear among them. He spotted the same tendencies as Dentan did—an onrushing thunderstorm excited massive, and to a Westerner, irrational fears.

It is interesting that fear still plays an important part in the worldview of the Semai—at least in the view of a photographer who was born 10 years after Dentan published his book, a year after Robarchek’s article came out. So important that he likes to capture that look in his work. The exhibit is open daily 10:00 AM to 10:00 PM and admission is free.