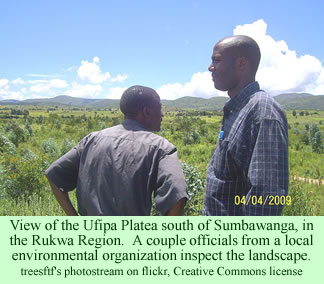

In a 1989 article, Willis describes how the agriculture of the Ufipa Plateau, where the Fipa people live in southwestern Tanzania, may have been a factor in helping foster their peacefulness. Finger millet, he writes, was the staple crop. The people kept large numbers of cattle, chickens, goats, pigeons, and sheep, with the numbers of cattle being the major mark of their wealth.

The fact that the plateau is virtually lacking in forest cover has precluded the possibility of nomadic, slash and burn agriculture, which was common among the other Bantu peoples in the region. As a substitute, the Fipa were forced to develop a unique style of agriculture based on raised-bed compost mounds. Willis explains that their agricultural system was six times as productive as that practiced by their neighbors, but it required the people to live in stable, long-term villages. Their peaceful culture of intense sociability may have developed as a result.

The fact that the plateau is virtually lacking in forest cover has precluded the possibility of nomadic, slash and burn agriculture, which was common among the other Bantu peoples in the region. As a substitute, the Fipa were forced to develop a unique style of agriculture based on raised-bed compost mounds. Willis explains that their agricultural system was six times as productive as that practiced by their neighbors, but it required the people to live in stable, long-term villages. Their peaceful culture of intense sociability may have developed as a result.

The problem is that Willis did his field work among the Fipa from 1962 – 1964, with a return visit in 1966. Are they still as peaceful as they were 45 years ago? Is their agricultural technology as productive as it was then?

A recent article in one of the major African news sources, Allafrica.com, does not answer the first question, but it does provide some significant insights into what is still the major economic activity of the region—agriculture. The article focuses mostly on numbers, such as the tons of fertilizers used and the tons of crops produced, for two regions of southwestern Tanzania, Rukwa and Mbeya. Most of the traditional Fipa territory is now encompassed by the Rukwa Region of the country, between Lakes Rukwa and Tanganyika, but the northwestern edge of the Mbeya Region also includes what was a part of Ufipa.

The article indicates that the two regions are the breadbasket of Tanzania, producing surplus food crops to help feed people in poorer regions of the country. While the two regions have excellent soils and a good climate for crop production—the natural resources are outstanding—it is clear that the Fipa are in the process of giving up their raised-bed composting style of farming.

The Regional Commissioner for the Mbeya Region, Mr. John Mwakipesile, describes how hard the farmers work for their crop successes. They have seen their lives improve, he says, as they continue to invest in their farms. “People have been able to send their children to school, cater for their health when they fall sick, build modern houses, buy cars and even open up businesses by using money generated from the agricultural produce,” he said.

Mr. Daniel Ole Njoolay, Regional Commissioner for the Rukwa Region, expresses a similar opinion. Everyone is very hardworking—people who don’t work hard on their farms are looked down upon as outcasts, an attitude that is passed down through the generations. He added, “we have never experienced [a] food shortage or hunger in [the] Rukwa Region.”

The advent of high technological inputs into food production has clearly had an impact on the Fipa. The article cites many figures—growth, growth, growth—from both areas, but it is simpler to concentrate on just those for the Rukwa Region. The acreage under cultivation in Rukwa grew from 68,440 in 2005 to 109,388.7 last year, according to Mr. Njoolay. The number of power tillers increased from three in 2005 to 225 last year, and the number of tractors from 54 to 85. The usage of “improved seeds” grew from 323.6 tons in 2005 to 4,026 tons last year. Farmers in Rukwa used 5,173 tons of fertilizers in 2005, and 18,644.5 tons last year.

The figures go on. The number of cattle dips increased from 13 to 36. In 2005, Rukwa had 20,191 hectares of irrigated land, which grew to 27,136 hectares last year. And finally, for the region, the harvest of food crops increased from 1,058,377.5 tons to 1,969,873.8 tons over the period 2005 through 2010. The article reports similar increases for the Mbeya Region.

Allafrica.com concludes that the hard work, combined with the excellent growing conditions, foster excellent crops for the people of that part of Tanzania. It is not clear, however, if the people of the plateau have completely abandoned their traditional, raised-bed, composting gardening techniques. An anthropologist needs to replicate the field work of Willis a half-century ago on the Ufipa Plateau to see how these the changes in agricultural technology may be affecting social conditions.