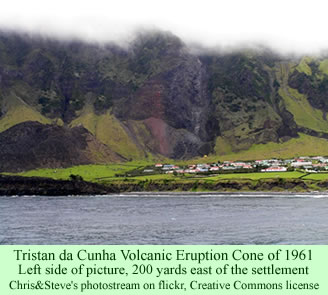

Fifty years ago, on October 8th, 1961, two months after the rumbling and shaking had started, a new volcanic cone shattered the earth only two hundred yards east of the settlement on Tristan da Cunha. This past week, the British media have been commemorating the eruption, and the evacuation of the islanders that had become necessary.

Perhaps the best narrative of the events is in Peter A. Munch’s book Crisis in Utopia, which surveys the history, values, and social structures of the islanders, plus, of course, the traumas the people endured when they were relocated to England until late 1963.

Perhaps the best narrative of the events is in Peter A. Munch’s book Crisis in Utopia, which surveys the history, values, and social structures of the islanders, plus, of course, the traumas the people endured when they were relocated to England until late 1963.

The minor tremors that started on August 6th, 1961, became much worse on Sunday, October 8th. A heavy shock broke loose a part of the cliff face directly behind the village, though without causing any damage. But on the eastern side of the settlement, which is on the north coast of the volcanic island, buildings started to heave. The people decided to spend the night, for their own safety, with others in the western end of the community.

The next afternoon, cracks developed in the earth about 200 yards to the east of the settlement. A large fissure opened and a sheep fell in, but while it bleated, the crack rose and the sheep jumped out. It resumed its normal life—eating grass—but the crack continued to rise. What had been a fissure in the earth became a mound, then a small hill, rising at the rate of about 5 feet per hour. By dusk it was 30 feet high.

It was too late to leave the island in the dark, but everyone realized that evacuation was essential. So to get safely through the night, the 264 islanders, carrying only essentials, plus additional expatriates living on the island, had to walk to another fairly level spot a couple miles away, the Potato Patches, a gardening area. There was no shelter at the Patches, so almost all the people spent the night in the open, in a cold drizzle.

The following day, Tuesday October 10th, the islanders walked back to the settlement and saw the new lava cone, now rearing high above and spitting stones and lava. Fortunately, a couple fishing vessels were anchored off shore. Though much too small to shelter the entire population overnight, they were prepared to take the people to temporary safety, on nearby Nightingale Island. There, the islanders had a number of fishing huts, which could safely shelter the people for several more days if necessary. The longboats of the islanders ferried the people out to the Tristania and the Frances Repetto, which took them to Nightingale.

The Islanders had wanted to have six men remain on Nightingale, with a longboat and rifles, so they could return to Tristan and shoot the dogs. There had not been time to round up the animals, and the people were afraid that, after a while, the dogs would become hungry and turn on the livestock for food. They felt the cattle, at least, might be able to survive if left to fend for themselves, perhaps for even a fairly long human absence.

But the following morning, the 11th, all of the Tristan Islanders were ordered to board the Tjisadane, a Dutch liner that had just arrived. It was headed for Tristan anyway, planning to pick up three people and take them on to Cape Town. The men were told to hand over their rifles. The Islanders were not told that the Colonial Office in London had decided during the night that the evacuation from Tristan would be permanent. The bureaucrats had apparently decided that allowing people to live on the remote island was more trouble than it was worth.

The articles on the BBC website on October 4th and on October 5th discuss the fate of the islanders when they reached England weeks later, after a brief stopover in Cape Town. They lived at first in huts on the abandoned Pendell Army Camp, in Merstham, Surrey, until late January, 1962. They were then moved to much nicer permanent homes in Calshot, in Hampshire, near Southhampton. They were welcomed into the community and many were able to get jobs. They began to learn how to get along in a modern, industrial economy.

But they also began contracting chest infections and bronchitis from the unaccustomed English weather. With homesickness increasing, they wondered when they would be able to return to their homes.

The news reports last week don’t discuss the government’s strategy in the early 1960s of trying to force the islanders to stay in England. Nor do they mention the growing suspicion by the Islanders themselves that what they wanted—to return to Tristan—was not what the government wanted for them.

The people, used to accepting directive from others with superior status, were not immediately able to take matters into their own hands and present a united front to the government. Making demands was never part of their style. But, as Munch recounts the story, they slowly, haltingly, made plans to send back to Tristan a bunch of men to see what conditions were like. The first group of 12 men returned in September 1962.

They reported that the volcanic activity had died down, that the settlement was basically unhurt, and they started the rebuilding process. The people decided to move back, even if they had to make the arrangements themselves. Prompted, and perhaps shamed, by the British press, the government ultimately backed down and in 1963 most of the remaining islanders returned to Tristan. A group of 51 people left England on March 17th, and the remainder, 198 people, boarded a liner on October 24th, 1963. A few had come to enjoy the modern life of conveniences and chose to remain in England.

Much as they were determined to return to their own homes, the islanders clearly appreciated the hospitality of the people of Calshot. They named the small harbor that British engineers subsequently built for them the Calshot Harbor, in appreciation for the people in Hampshire who had hosted them.

Ernie Repetto, now 85, remembered to the BBC that it had seemed quite nice in Calshot. “I was able to grow potatoes. I remember catching the bus to Southampton to see the ships in the docks. They were nice people there.” Mrs. Repetto had a slightly different take on the experience, however. “In England if you ain’t got money, you can’t live. In Tristan you can kill a sheep, catch a fish or grow potatoes and still have a happy life.”

The Tristan da Cunha Association, in cooperation with the government of the island, has mounted a special page on its website in commemoration of the anniversary. It contains an interesting account by Peter Wheeler, written in October this year, about the evacuation he had to supervise 50 years ago as the administrator of the island. The webpage also announces that the islanders are compiling a commemorative book about the events of 50 years ago, to be published on the anniversary of the return to Tristan in 2013.