Last Thursday, a federal jury in Cleveland, Ohio, convicted Samuel Mullet, Sr., and 15 of his followers for conspiracy and hate crimes in their hair and beard cutting attacks on other Amish people in 2011. The trial included three weeks of testimony, and it took the jury nearly a fourth week to reach its verdict. The judge will impose the sentences in January. The testimony was at times lurid, but it also provided fascinating glimpses into Amish customs and more specifically into the ways of the psychopathic leader of the breakaway Amish sect.

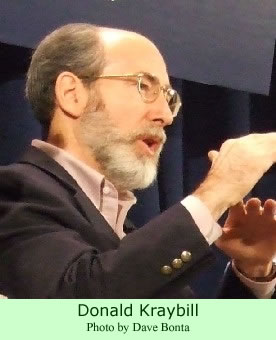

One of the highlights of the trial was the testimony by Donald Kraybill, eminent authority on Amish society. Kraybill, who is on the faculty of Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania, testified at the beginning of the third week of the trial. On Monday, September 10, he told the jury that the humility and nonviolence practiced by the Amish are based on their beliefs that Jesus himself exemplified those virtues. “The Amish believe that we should do no harm to anyone in any way,” Kraybill said.

One of the highlights of the trial was the testimony by Donald Kraybill, eminent authority on Amish society. Kraybill, who is on the faculty of Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania, testified at the beginning of the third week of the trial. On Monday, September 10, he told the jury that the humility and nonviolence practiced by the Amish are based on their beliefs that Jesus himself exemplified those virtues. “The Amish believe that we should do no harm to anyone in any way,” Kraybill said.

He added that central tenets of their beliefs are “the rejection of revenge, the rejection of force, and forgiveness…” He described a 2006 Amish leadership meeting held in Pennsylvania during which hundreds of bishops overturned some excommunications that Mullet had ordered against a few of his followers. They had disobeyed him by moving away from his community.

According to Kraybill, the excommunications Mullet ordered were not for religious or biblical reasons. Kraybill described this dispute as comparable to an earthquake in the Amish world. Federal prosecutors argued that this dispute was what provoked Mullet’s subsequent fury and led to the hair and beard cutting attacks on his disobedient followers.

News reports last autumn describing the attacks were clarified and amplified during the trial. For instance, Barbara Miller, a sister of Mr. Mullet, testified about the events that occurred to herself and her husband Marty in their home at this time last year. She and her husband had moved out of Mullet’s community near Bergholtz, Ohio, as a way of ending their dispute with him and his autocratic ways.

She said that as a result of the split, she and her husband had had strained relations with six of their children and their spouses, but she was initially thrilled when her family appeared at their doorstep late one night last September. When she saw her son Lester at her door, she said she wanted to hug him. But her joy quickly turned to terror.

Her son and the others pushed past her. Lester grabbed his father by his beard and pulled it so hard it distorted his face. While the women chopped off Barbara’s waist-length hair, the men shaved Mr. Miller’s lengthy beard. “I started praying ‘forgive them God,’” Mrs. Miller testified, but she added that one of her sons screamed at her, “God is not with you.” To the Amish, long hair, uncut since baptism and marriage, is symbolic of their religious identity. Having it cut off has been humiliating to the victims.

News accounts over the past month of the trial have described the other attacks by the Bergholtz Amish. The defense never denied that the attacks took place, but they characterized them as community disputes, not hate crimes—Mr. Mullet’s way of imposing discipline on his followers. No one charged him of any personal involvement in the attacks, but the government prosecutors did charge him with being the mastermind behind them. The jury finally agreed.

Testimony at the trial included some evidence of the ways Mr. Mullet liked to treat members of his congregation. One woman, not named in news accounts, told the jury that Mullet had forced her to have sex with him, his way of turning her into a better wife, she said. The judge warned the jury that there were no sex crimes charges against Mr. Mullet, so they should only consider the testimony in relation to the actual indictments.

The lady testified that her husband had had a mental breakdown and was in a hospital. In response, Bishop Mullet suggested that his troubles stemmed from his dissatisfaction with their marriage. He suggested that she move into his home with him so he could do some marriage counseling.

His counseling at first consisted of hugs, then of kissing and her sitting on his lap. Even asking for hugs was upsetting for her, since Amish beliefs encourage modest behavior. She went along with him because she believed she might help her husband. Then he insisted that she come into his bedroom, despite her opposition.

She moved back with her husband when he was released from the hospital, but continued to visit Mullet at his insistence. “I was afraid not to go,” she told the jury. When she finally told him that the relationship had to stop, he told her she was a whore. She and her husband solved the situation by abruptly packing their clothing and leaving for Pennsylvania.

Others also testified about the way Mullet had disciplined his followers by requiring them to spend time sitting in a chicken coop reflecting on the errors of their ways. Other women testified that they had had to submit to Mullet’s style of sexual counseling.

Testimonies for the defense emphasized that the hair cutting attacks were part of a series of family squabbles, which included disputes about money, child-rearing, and the ways people dressed. Last Thursday, the jury concluded that the prosecutors were right. The attacks were hate crimes, the result of a conspiracy. Sentences could include ten years or more in prison for Mr. Mullet and his 15 followers.