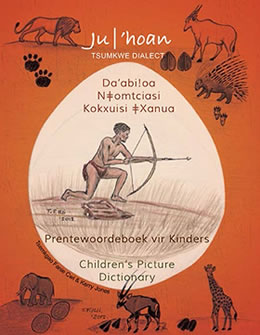

The University of KwaZulu-Natal Press has announced the publication of the Ju/’hoan Children’s Picture Dictionary, for 250 South African rands (U.S. $22.53), by Tsemkgao Fanie Cwi and Kerry Jones. The book will probably make important contributions to Ju/’hoansi educational programs.

According to the announcement of the book on the website of the press, the wire bound, 134 page volume represents an attempt to give Ju/’hoansi children printed material inspired by local literature in their own language.

According to the announcement of the book on the website of the press, the wire bound, 134 page volume represents an attempt to give Ju/’hoansi children printed material inspired by local literature in their own language.

The publisher’s website states that the work is trilingual, in English, Afrikaans, and the Tsumkwe dialect of Ju/’hoansi. The Ju/’hoan people themselves designed and laid out the work, choosing the themes and lexical entries they wanted to represent their community and their traditions. They created the illustrations and artwork, which convey their views of their daily lives.

In the words of the website, the entries provide “rare and fascinating insight into the staple artefacts and traditions of San life.” The work includes a CD with Ju/’hoan speakers pronouncing their words. The CD also includes photo and video galleries plus information about the Ju/’hoan people. And, the package includes a printable language game.

“This unique and special project/book is a must for anyone with an interest in San life, the San people and their communities,” the university press concludes.

Background about this effort can be gained from The Ju/’hoan San of Nyae Nyae and Namibian Independence, the exhaustive recent work by Megan Biesele and Robert K. Hitchcock. The book emphasizes the important decision by the Ju/’hoansi living in the Nyae Nyae Conservancy 25 years ago that their children should be taught in their own language in their schools, using materials printed in Ju/’hoansi.

The authors tell us that the Village Schools Project, developed in 1989 by educational consultants and the Ju/’hoan people, was the vehicle for realizing their aims for educating their children. An essential aspect of the VSP was to locate the schools, as much as possible, right in the rural Ju/’hoansi settlements themselves instead of in Tsumkwe, the central town of the region. Ju/’hoansi thinking was that it was essential for their educational programs to be based on, and developed out of, their traditional, permissive, hands-on approaches to teaching kids skills necessary for life in the bush.

Their educational system had worked, for them, for millennia. It emphasized the processes of oral, creative group learning. The VSP project captured the Ju/’hoansi emphasis on having high standards for their schools. They wanted their children to have printed materials in Ju/’hoansi such as folktales, histories, primary school readers, the texts of songs, and dictionaries. Their children would learn how to get along in the modern world, but the skills they absorbed would be based on their own culture and values.

Although the two authors express optimism about the schools in their book, a news story in July 2011 pointed out that there are still serious problems with schooling in the Nyae Nyae Conservancy—truancy, lack of materials, and difficulties in teaching the children in Ju/’hoansi.

The publication of this new dictionary suggests that the people are still striving to improve their education programs and that at least the difficulties of teaching the children literacy, in their own language, may soon be solved.