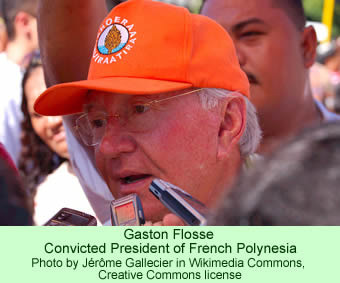

Corrupt politicians are hardly news anywhere in the world, but Gaston Flosse, the President of French Polynesia, might deserve a prize as an extreme example of the phenomenon. The highest court in France last Thursday upheld his conviction for corruption last year, which resulted in a suspended jail sentence for four years, a fine of US$170,000, and a three-year ban on holding public office.

He has appealed to the President of France, Francois Hollande, for a special presidential pardon. He has been convicted in two separate cases of taking bribes and of running a network of phony employees during the 1990s in order to build the influence of his party. The verdict of the court last week was sent to the French High Commission in Tahiti for it to carry out the requirement of the law—that he be removed from the office to which the Tahitians, and other citizens of French Polynesia, elected him nearly 15 months ago.

He has appealed to the President of France, Francois Hollande, for a special presidential pardon. He has been convicted in two separate cases of taking bribes and of running a network of phony employees during the 1990s in order to build the influence of his party. The verdict of the court last week was sent to the French High Commission in Tahiti for it to carry out the requirement of the law—that he be removed from the office to which the Tahitians, and other citizens of French Polynesia, elected him nearly 15 months ago.

Flosse claimed that the French judiciary had lost its credibility in reaching its decision. He repeated his innocence and said, in a statement, that the court had denied the results of democracy. The French Polynesian voters were aware of the conviction when they went to the polls at the beginning of May last year, yet they elected him anyway, he contends.

His practice of running a scheme for phantom jobs from the presidential office 20 years ago has been referred to as “the biggest case of its kind in French legal history.” Flosse maintains his innocence, saying that all of the job contracts were approved by the French high commissioners.

On Friday, his opponent in the election last year, Oscar Temaru, called for the territorial assembly to be dissolved and for fresh elections. The two men have taken very different positions on the fundamental issue of the Tahitian relationship to France. Flosse has steadily maintained the importance of French Polynesia remaining an integral part of France while his opponent, Temaru, has been elected to the office of territorial president several times on a platform of gradually moving toward independence.

Flosse has appealed his sentence to the Court of Criminal Appeals in Papeete, the capital of French Polynesia, asking it to set it aside. That court is expected to consider the request on August 21. Also, he indicated that he intends to take his case to the European Human Rights Court. He wants that body to hear his contention—that his basic liberties have been violated by the French judiciary. The irony of that contention is that the man who has so based his career on the viability of close ties to France is now castigating the judiciary of that nation when it condemns his decades of corrupt practices.

On Tuesday this week, the French High Commissioner in Tahiti, Lionel Beffre, announced that he would defy the supreme court’s ruling last week. He indicated he would delay enforcing the order of the court, pending a decision on a pardon by President Hollande.

The vote in French Polynesia that brought Flosse to power on May 5, 2013, was apparently based on the fact that the economy of the territory is not at all good. It was neither a vote in favor of, nor opposed to independence, but a vote against the then incumbent, Temaru. The economy of the territory has been growing weaker for many different reasons. France has warned its territories that if they move toward independence, they will risk the loss of French financial subsidies, further harming their already fragile economies.