Tahitians living near a subdivision under construction on Huahine are protesting the destruction of their natural environment, especially the backfilling of land on the shore of a small lake. An article last week in La Dépêche de Tahiti, a major Tahitian daily newspaper, describes the growing local controversy.

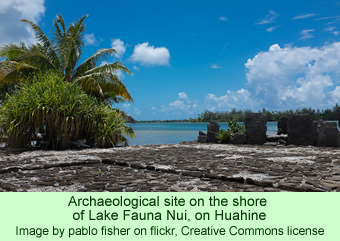

The north end of Huahine, one of the important islands in the Society Islands chain, is noted for its large, tidal lake, Lac Fauna Nui (Large Lake Fauna), a two and one-half mile long body of water. Numerous ancient sacred stone enclosures called marae, constructed by the Polynesians before the arrival of Europeans, are located along the shore of Fauna Nui.

Just 250 feet off the southwest corner of the large lake is the small lake affected by the development, called Lac Fauna Iti (Little Lake Fauna). The small lake is about one mile northeast of Fare, the major town on Huahine. To judge by the images on Google Earth, the little lake is round and between 750 and 800 feet across.

The backfilling that the Tahitians are protesting is easily visible on Google Earth on the north side of the small lake, which provides an image dated April 12, 2014. The subdivision under construction is on the opposite side of the road leading north toward the Huahine airport.

At a meeting attended by the newspaper reporter, residents expressed concern that the growing fill has removed reeds, part of the thick vegetation around the lakeshore. The reporter, Malissa Itchner, quotes a local man, Claude Chong, who explains that the thick reeds perform a natural filtering action to protect the fish fry.

Mr. Chong decries the growing embankment because it is encroaching on the little lake. He believes that protecting the natural ecosystem is essential for the inhabitants of the Maeva district, a rural area at the northern end of Huahine. “What will we leave our children and grandchildren [if the destruction of the lake continues]? We ask [the] owners to stop their work immediately,” he says in the words of the Google translation. He alleges that public officials may have been corrupt when they signed off on permission for the development.

Benjamin Caminn Teiho, who represents an association called Maeva Ia Ora, also challenges the destruction. He suggests that the owners of the development did not have proper authorization for filling in the lakeshore. He does not express opposition to the development itself, but his group is vehemently opposed to destroying the little lake. “This is our hatchery our nursery to fish, and developers do not respect this ancient site,” he says.

Ms. Itchner contacted the manager of the subdivision, who at first expressed an unwillingness to speak on the telephone, but then went on to defend the development. The reporter carefully describes the natural filter between the two lakes: stones, sand, seaweed, and reeds, and the abundance and variety of fish species that are harvested from the big lake. But the emphasis of her informants on the importance to them of the natural ecosystem, beliefs derived from their traditional Tahitian culture, is most revealing.

Richard Maiterai told the visitor that their ancestors placed stones around the small lake to help the fish and to provide a protected environment, so the fish eggs could safely hatch. They didn’t have to provide an exit from the small lake to the much larger one because the reeds and tides allowed for safe exchanges between the two bodies of water. Mr. Maiterai explained to Ms. Itchner that the sacred tradition, the tapu, was very powerful at that spot, and it was respected. As an example, he said that menstruating women traditionally would not enter the lake.Although he compared traditional sources of pollution with the contemporary violations of the lake, he especially condemned the latter.

Huahine, while not overflowing with tourists as much as Tahiti, Bora Bora and Moorea, retains stronger connections to traditional Tahitian culture than the others. Levy (1973) explains in some detail the belief in tapu that Mr. Maiterai referred to. It evidently was a traditional Tahitian concept combining the ideas of sacredness and prohibition. A small lake might be sacred enough that polluting events—a menstruating woman entering the water, or backfill from a development on its shores—would not be allowed. Either of the two aspects of tapu, the sacred or the prohibited, might predominate in any given situation, according to Levy, depending on circumstances.

The English word taboo, a prohibition based on the sacred nature of something, is derived from the Polynesian tapu, or tabu. For the Tahitians, the traditional concept of tapu had even broader ramifications. Levy (1973) writes that tapu not only prevented activities thought to be contaminating, it also provided the basis for the political and social controls of society. Those controls helped prevent conflicts from degenerating into acts of violence and formed their mostly peaceful society.

Traditional Polynesian terms, such as tapu, and the controls it implied, were still important in rural Tahitian society when Levy did his field work on Huahine from 1964 to 1966. To judge by Mr. Maiterai’s comments to the reporter last week, they still are valued, at least to an extent for some Tahitians.