A support group has launched a campaign to foster awareness and actions that will help Inuit women who suffer from violence within their families. Nunatsiaq Online, reporting on the story early last week, indicated that the focus of the new program is to involve other people—bystanders, office colleagues, neighbors—in suspected cases of violence.

Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada launched its program with the three tag lines, “Believe; Ask; Connect.” Rebecca Kudloo, the president of the organization, told the news source in an email, “We can all help end violence in our homes and communities. We want to encourage and support people to help others. Together we can make changes by listening and talking.”

The three tag lines suggest that people should believe the evidence they perceive when a woman appears to be a victim of family violence, ask her how she feels the issue might be handled best, and then help her connect with an appropriate support service. The campaign by the Pauktuutit group has been supported by a grant of $75,000 from Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. The group has just learned that it will receive more federal support as well.

The three tag lines suggest that people should believe the evidence they perceive when a woman appears to be a victim of family violence, ask her how she feels the issue might be handled best, and then help her connect with an appropriate support service. The campaign by the Pauktuutit group has been supported by a grant of $75,000 from Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. The group has just learned that it will receive more federal support as well.

The news service reported that the director of a women’s emergency shelter in Iqaluit, Suny Jacob, said that she would support any efforts to raise awareness about the problem of family violence. But she expressed skepticism that focusing on the assistance of bystanders would be enough. Many Inuit have a lot of problems of their own and may be reluctant to become involved in the issues of others. They might fear that they could be required to be interviewed by the police, or perhaps even to participate in court hearings, all of which would demand their time and efforts.

Jacob said that since many people are so involved with their own lives, they don’t have too much time for getting involved with the lives of others. She feels that the most important thing is to support mental health services and emergency shelters. That way, women who are the victims of violence have services outside the family to which they can turn for help.

Kudloo responded that while some bystanders may be reluctant to come to the aid of a battered woman, she hopes the campaign by her group will change the general attitude of people toward the issue. Violence in the home is not just a private matter. It is important, she said, to “encourage people to break the silence. It’s OK to talk about it and say it’s not OK to hurt others.”

The news story, quoting a report in 2013 from the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, a component of Statistics Canada, said that the rate of violence against Nunavut women in 2011 was 13 times higher than the rate for the rest of Canada. It went on to indicate that 1,715 women in Nunavut were the victims of violent crimes that were reported to the police in 2011, compared to 1,014 men that year. When only statistics of sexual crimes were examined for that year, Nunavut had a rate of 1,135 per 100,000 people, compared to 99 per 100,000 in the rest of the nation.

Earlier news reports have made it clear that one of the major reasons for the violence in Inuit society is the breakdown of the traditional social structure. The violence in Nunavut, according to a story in 2011, appears to be a direct result of the historical trauma of the Inuit having moved—or having been pressured to move by the government—off the land and into settled communities, and in the process, of abandoning their traditional ways.

But the reasonable question is, how much violence existed against women in traditional Inuit societies, out on the land? A recent journal article argued that violence was present in traditional Inuit society before the period of historical traumas began. It continued during the worst of the traumatic episodes, and it continues today. The author of that article cites a variety of Inuit works to document her assertion—that the Inuit past cannot be idealized, and that their contemporary social realities must be confronted realistically.

However, Briggs (1974) provided a nuanced view of the traditional Inuit women and the society they lived in. She wrote that while Inuit men and women were ambivalent about loving and being loved, they did not, at least in their traditional culture, exhibit institutionalized gender conflicts, and they showed very little tensions between the sexes.

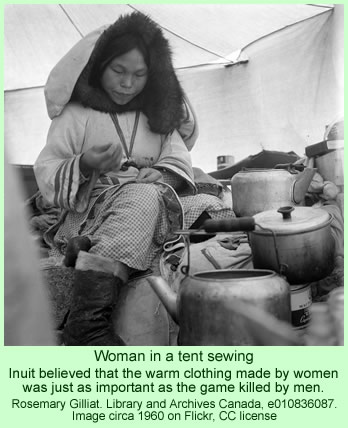

An important feature of Inuit marriages was that the men and their wives had very clear roles. The men were the hunters, enduring the frequently very difficult, dangerous tasks involved with providing for their families. They also did all the very heavy work and repaired not only their own tools but everything around the camp. The women did a lot of work around camp such as sewing, child care, and cooking.

Briggs (1974) makes the point that both spouses credited each other for their respective contributions. Both thought the work of the other was absolutely essential. Neither could live without hunting or warm clothing. Both were critically important—at least in their traditional society. The work of both partners was interdependent and complementary, and while some women could help a bit with the hunting, and some men could do a little of the housework, they believed that the work of the other was indispensable and that they were basically incapable of doing it.

In public, men and women would maintain a formal separation—when a party of strangers approached the village, the men would go out to greet them, while the women would retreat to the house and make tea for when the visitors were brought in. Behind the formal, public view, however, Inuit couples—particularly people who were middle aged or older—often had close relationships. In the privacy of their evenings, they would share experiences, reminisce about the past, play cards, and perhaps enjoy foods that they kept only for themselves.

Briggs (1974) did not romanticize the Inuit. Rather, she provided a careful record of her perceptions of life in the traditional Inuit community out on the land. The tragedy appears to be the historical traumas which fostered violence among them. The practical discussions among activists such as the Pauktuutit group and the Inuit women’s crisis center are essential, but so are the historical facts recorded in the literature by scholars such as Briggs and the possibilities that they may suggest.