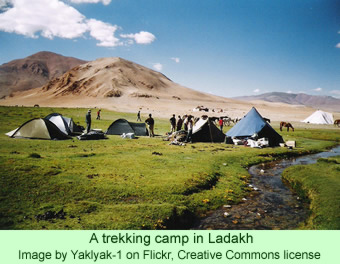

Thinlas Chorol, a Ladakhi woman, has challenged a profession that previously had been a male preserve by founding a trekking company staffed entirely by women from rural Ladakh. In the process, Ms. Chorol’s determination in establishing her new business exemplifies the traditional equality and strength of Ladakhi women.

The writer of a news story last week about the company, Gagandeep Kaur, opens her report by indicating that Ladakh is “probably one of the best places in the world for a woman to live.” Ms. Kaur, an independent journalist based in New Delhi, specializes, in part, on writing about gender issues.

The writer of a news story last week about the company, Gagandeep Kaur, opens her report by indicating that Ladakh is “probably one of the best places in the world for a woman to live.” Ms. Kaur, an independent journalist based in New Delhi, specializes, in part, on writing about gender issues.

Chorol was a native of Takmachik, a small village in Ladakh, and she studied in school until the tenth level before entering the Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL), a progressive non-governmental organization that promotes advances in education. Her determination led her to Leh, the major town of Ladakh, where she got into trekking since she loved to explore the mountains of the region. She decided to begin a career as a trekking guide.

She worked for two years with a travel agency associated with SECMOL, called Around Ladakh with Students. Then, in 2008, Chorol spent a spring semester at India’s National Outdoor Leadership School taking such courses as backpacking and whitewater rafting. Subsequently, she served as an instructor’s aide for a mountaineering course at the school. Then, she taught a course in mountaineering at the Nehru Institute of Mountaineering in Uttarkashi, a mountainous district of northern India outside Ladakh.

After that, she worked as a freelance guide, but she was unable to get a position with an established travel agency—they hesitated to hire a woman. “In spite of being well qualified, it was extremely difficult to find any opening[s] because of my gender. It was just presumed that men are more suitable as trekking guides,” she told Kaur.

But Chorol had the insight that at least some female tourists would prefer guides who were also women. She took on various guiding jobs, but she obsessed about her first love—trekking. So she decided to launch her own business in 2009 with a commitment to hiring only other women as her employees.

She started the business, called the Ladakhi Women’s Travel Company, with only an office manager, two other guides, and two porters. She had to borrow money from her family to get started, but she has broken the myth that only men can be trekking guides. Kaur quotes one of her employees, Dolma, a 24 year old student, who reports that she loves being a guide. Dolma’s family was reluctant to have her become one, but when they realized that other women were working for Ms. Chorol, they accepted the idea.

Dolma is a first-year university student seeking a Bachelor of Arts degree, but she seems to appreciate being employed by Chorol at the tourist company. She explains how Chorol carefully trained her for a year before she was allowed to go out as a guide herself.

Chorol tells the writer that since she prefers to hire her employees from the remote villages of Ladakh, they require a lot of training, especially in communicating with tourists. Because of their isolated backgrounds, they do not really know how to talk effectively in English with the visitors, she explains.

One of the problems of running a tourist business in Ladakh is that tourism virtually shuts down in the winter since travel in the region becomes nearly impossible. Thus, tourism and trekking last only from April through October each year. But one of Chorol’s major achievements has been the fact that women are now being hired by other travel agencies in Ladakh as trekking guides. Families are comfortable with their girls entering the field.

Chorol’s ability and determination to lead Ladakhi women into significant places in the growing travel industry is not surprising. Earlier news stories about Ladakh have made it clear that the place of women in traditional Ladakhi society was already quite strong—an important aspect of their famed peacefulness—and that strength has not appeared to weaken very much due to increased contact with modern ways.

This expansion of the roles of Ladakhi women also fits in with what Helena Norberg-Hodge (1991), wrote in her book Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh. She indicated that human roles are not clearly defined in Ladakh—people move about the house doing what needs to be done, seemingly without coordination or direction from anyone.

Women have somewhat different roles from men, but their status is not only secure, they have a relatively strong position. Since the economy of their traditional society is based on the home, which the women control, they make all the major decisions. Norberg-Hodge wrote that she was struck, when she first entered Ladakh, by the uninhibited smiling of the women. They moved about joking and freely, unselfconsciously interacting with the men.

“Though young girls may sometimes appear shy, women generally exhibit great self-confidence, strength of character, and dignity,” the author wrote (p.68). The news report about the confidence and accomplishments of Thinlas Chorol certainly bears out that observation by Norberg-Hodge.