Doctors in the 1930s described a series of fainting spells by women on Tristan da Cunha as female hysteria, a diagnosis that would no longer be acceptable to medical authorities.

Instead, Lance van Sittert analyzes them as political expressions. In a recent journal article, the Associate Professor of Historical Studies at the University of Cape Town describes his research based on reports by visitors to the island in the first half of the 20th century. He concludes that the episodes of fainting were a way for island females to make political statements against male supremacy. His background information about conditions for women and the social structure on Tristan during the period add a lot to our understanding of that society.

The author points out that 19th century romantics maintained an unrealistic view of Tristan da Cunha as a utopia, which it was not. The island had become polarized, with an elite of Scandinavian-looking upper class people and a much more swarthy looking, much poorer underclass. Outside observers noted that members of elite families on the island referred to the lower class people contemptuously as “the poor.”

Professor van Sittert argues that race, class, and wealth tended to be perpetuated on Tristan since young people with fair skin were highly prized as marriage partners, while young people with darker skin had a harder time finding a mate. Discrimination on the island resulted in the people with darker skin remaining poor. Wealth begat wealth, he writes, and poverty begat poverty, since the people stayed within their differing racial groups.

Another important social factor on the island during the first half of the century was the isolation of Tristan da Cunha. The island people took pride in their incredible isolation, but since relatively few vessels visited Tristan there was a limited diversity of potential marriage partners. However, van Sittert maintains, since there were 1.5 unmarried men for every unmarried woman on the island, the young women did gain some sense of security from the demographic situation. They tended to have lots of male admirers lined up in the living rooms of their parents.

After about 1900, Tristan women started undercutting the pattern of male dominance because they were more literate than the men. Their superior reading and writing skills allowed them to more effectively interact with powerful figures in Europe and solicit charity and support from them than the Tristan men could do.

Countering that, missionaries of the Anglican Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, on the island for most of the interwar period, typically had a goal of restoring the patriarchy. The arrival of the missionary Harold Wilde in February 1934 epitomized this tendency to repress island women. He was determined to end charity from the north, mostly secured by the women, by impounding all donations in a locked storehouse. In effect, he confiscated the donated goods, forcing the women back into a state of dependency.

Wilde left on a ship for home in February 1937, leaving the storehouse key with the Chief Islander, William Repetto, son of Frances Repetto, the matriarch of the society. The islanders may have expected that, with the dictator gone, Mr. Repetto would scrap the centralized control of the island storehouse. But he followed the instructions of his mother and declined to leave it open as it had been in the past. She reasoned that it was only an attraction to the lazy people (i.e., the underclass) who did not work hard and save up their goods for a rainy day.

The first fainting spell, by Frances Repetto herself, occurred in July 1937. She had had a history of fainting, labeled as “sleeping spells” over the decades, in response to crises on the island. The context in 1937 was the absence of Mr. Wilde and the agitation to open up the storehouse. In a situation where the woman is denied any political voice, and where the missionary had restored all symbols of male authority, Ms. Repetto’s so-called hysteria was really an expression of her frustration with political denial. Her sleeping spell expressed passivity and hopelessness.

Ms. Repetto’s performance was quickly mimicked by other women in her immediate family. They had no convulsions; they just fainted and moaned slightly from time to time. Some of them had many such spells in a single day. In August, the spells by unmarried women began to change from the submissive sleeping style of fainting to a more kinetic, loud, and defiant style, referred to as “fighting spells.” The victims started by fainting, but they soon changed into convulsions and jerking movements. Then, the women tried to tear off their clothes, grabbed at their breasts, and simulated arousal, though they soon subsided into semi-consciousness. The “fighting spells” were unique, a novel addition to the political arsenal of the Tristan women.

The spells continued in September with the married women joining the ranks of performers. The author argues that they represented “a generational revolt within female politics against the Repetto matriarchy and its enforcement of the new missionary morality on island youth (p.114).” The young women had invented a unique way of performing to dramatize their issues. They had borrowed from the matriarch the spell, as well as, from the missionary, the ideal of the ecstatic vision.

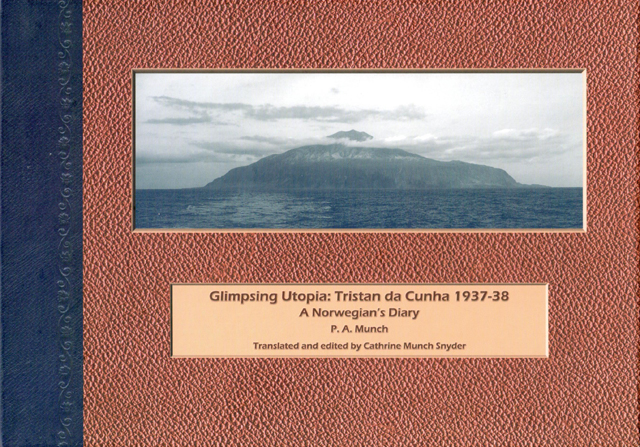

In December 1937 a ship arrived bringing the members of a Norwegian scientific expedition, including the sociologist Peter A. Munch, for a four-month stay and, on the same vessel, the dictatorial minister Harold Wilde. Van Sittert’s examination of the information recorded by the Norwegians during their four month stay on the island shows that the fainting spells were more suggestive of gender politics than of gender pathology.

The author maintains that Munch followed his medical colleagues on the expedition in diagnosing the condition of the women as “spells.” He wrote, in his Sociology of Tristan da Cunha, that they were “a form of unconscious, or only half conscious, outbreaks of repressed temperamental dispositions (p.74).” Van Sittert strongly disagrees, and he makes his point by recounting the history of the outbreaks of fainting.

However, the diary kept by Peter Munch, translated and edited by his daughter Cathrine Munch Snyder and published in 2008, reveals more freely than the earlier published works by the famed ethnographer what van Sittert refers to as a “medieval feudal estate” on Tristan. It was “presided over by an alcoholic and sexually predatory missionary-lord whose immiserated and illiterate serfs lived in daily dread of his whims (p.115).”

Some problems with van Sittert’s presentation need to be mentioned, however. He castigates the investigations of ethnographers in general, who assume “not only an essentially static society governed by custom, but also the absence of conflict based on class, race or gender and hence of any island politics (p.101).” His sweeping dismissal of ethnographic work is highly questionable. Furthermore, he frequently places sarcastic quotation marks around words and phrases, which cheapen his otherwise interesting arguments. Despite these weaknesses, van Sittert provides a lot of interesting information about social conditions on the island during the first half of the last century.

van Sittert, Lance. 2015. “Fighting Spells: The Politics of Hysteria and the Hysteria of Politics on Tristan da Cunha, 1937–1938.” Journal of Social History 49(1): 100-124