Perhaps the most basic question for anyone investigating the peaceful societies phenomenon is how they are able to maintain their peacefulness in the face of global economic and social pressures. Some answers are suggested by the Chewong, who still avoid anger, violence, and competition—and cherish the nonviolent interactions of their egalitarian society—despite the many challenges that confront them.

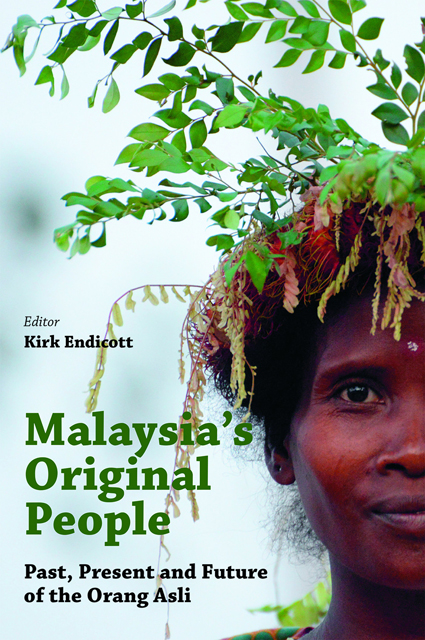

Since her first period of fieldwork with the Chewong beginning in 1977, Signe Howell has returned many times to their community to add to her archive of notes. She addressed the changes that she has witnessed, and the ways the Chewong keep adapting to the outside world, in an article she published last year in a book edited by Kirk Endicott about Malaysia’s original people.

Since her first period of fieldwork with the Chewong beginning in 1977, Signe Howell has returned many times to their community to add to her archive of notes. She addressed the changes that she has witnessed, and the ways the Chewong keep adapting to the outside world, in an article she published last year in a book edited by Kirk Endicott about Malaysia’s original people.

Her many visits over more than 35 years have given her a unique perspective on a fascinating society. For instance, at the time of her first fieldwork, the Chewong seemed to fit the description of an “immediate return society,” characterized by non-competitive values, an egalitarian ethos, and an economy founded on sharing and the absence of accumulated savings. Today, they spend whatever extra money they earn, so they now have an “immediate spending,” or “immediate consumption” society. But the net effect is similar—the individual is restrained from accumulating goods, with all the concomitant values that such accumulations often produce.

They have access to some money now to participate in the consumer economy, but they are ambivalent about completely assimilating into it and the values it represents. Many acquiesce, though some changes can be detected. They are yielding to the pressures of the larger society, and they are fascinated with consumer goods. Yet they still resist.

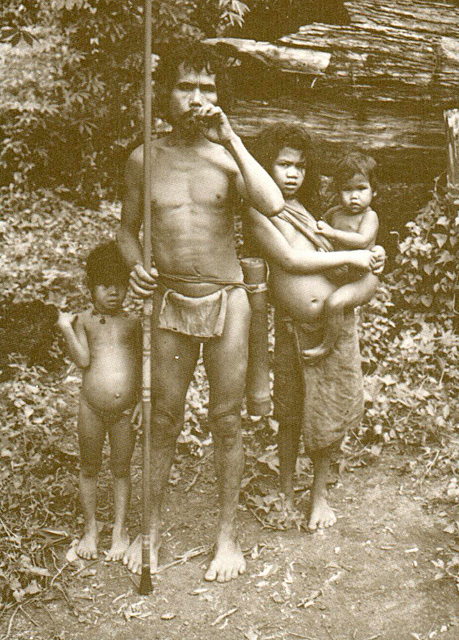

In some ways, the Chewong retain their older values. They thought of themselves in 1977 as gatherers and hunters and to some extent the middle aged and older adults still do. Most still accept their animistic religious beliefs, in which they interact on a daily basis with non-human, conscious beings in the forest whose rules must be followed carefully. Any failures to follow those rules could result in mishaps or illnesses. In effect, Howell argues, their social world still encompasses their spiritual surroundings—the forest spirits are animated beings to them.

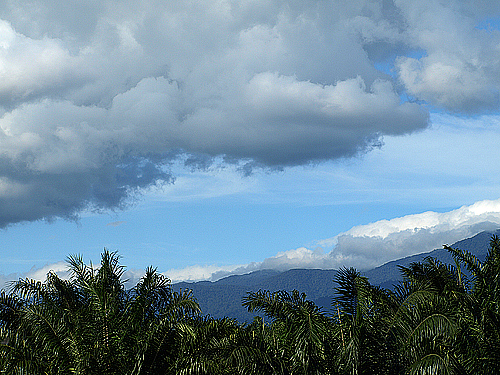

Most Chewong now live in a permanent village, often referred to as the “Gateway Village,” created for them by the government just outside the Krau Wildlife Reserve, where they have lived for centuries. The wildlife reserve is located in the Titiwangsa mountain range of Pahang State, in the central section of the Malay Peninsula. At first, the government provided only wooden houses for the Chewong, but now they live in brick homes with piped in water and electricity.

Howell carefully described the ways the Chewong have accepted—or rejected—the implications of permanent settlement that she has witnessed over the years. The government developed rubber and fruit gardens for the people, which the Chewong timidly started to use. But they soon abandoned the gardens since they preferred to harvest non-timber forest products to sell, rather than to fuss with the work of gardening.

By the 1990s, the people appeared to be moving out of the forest and into the Gateway Village, but the next time she arrived, the village was nearly abandoned. They had moved back into the forest. By 2008, however, many had moved back into the village. They have been unable to decide whether to live permanently in the cash society, with all of its advantages, or in the forest with its many benefits. But as of Howell’s most recent visit, the gateway village had over 100 inhabitants, the most it has ever had.

The people cultivate primarily in order to sell, not to eat. But several Chewong families remain in the forest, only rarely appearing in the village when a family member arrives to sell a forest product. While they clearly have a desire for consumer goods, many have not made a hard and fast choice about staying in the forest permanently or living in the village all the time. They have a fluid pattern in their accommodations to modernization.

One of the aspects of life that has not changed for the Chewong is their timid, often fearful relationships with outsiders, particularly the Malays and the Chinese. Their reactions are based on centuries of slave raiding and, since the 1900s, of being exploited by outsiders. When they are cheated or mistreated by outside merchants and government authorities, the Chewong react as they always have— by withdrawing from confrontations.

The cash economy is forcing changes on the Chewong. For one thing, they are spending an increasing amount of time on activities that generate cash. When they need more rice, or they need to make a payment on a motorbike, they may search in the forest for products that they can gather and sell. They are starting to cultivate rubber plantations—investing in their own future consumption.

One effect of the cash economy is that men are able to earn more money than women. As a result, men are becoming the decision-makers in the households, and they tend to spend the bulk of the money on things that they want for themselves.

A development that has had an important impact on the Chewong has been the establishment of the National Elephant Conservation Centre, Kuala Gandah, right next to the Gateway Village. Wild and orphaned elephants have been brought there since the late 1980s and it has become a major Malaysian tourist destination, attracting, in 2009, about 150,000 visitors. A few Chewong men have been hired to work at the park.

Howell noticed a number of Chewong adults and children converting to Islam in 2002, but during her visit a few years later she could not spot any traces of it. The missionaries had left the village so the people went back to their old ways. Christian evangelists have been more successful, since they keep coming back to the village every month to conduct a church service and to provide food and clothing to those who have converted. However, Howell finds that the understanding of Christianity by the converts is not very deep.

While she has witnessed many changes among the Chewong due to the influences of the larger society and its cash economy, she doubts that the gloomy scenarios proposed by some social scientists for hunter-gatherer societies will necessarily apply to the Chewong. They will not inevitably be subjected to increased poverty, disempowerment, and acculturation due to modernization. The Chewong demonstrate that they have complex motivations in the choices they make and it is difficult to predict how they will react to new situations that develop. They make their own decisions as best they can.

Howell, Signe. 2015. “Continuity through Change: Three Decades of Engaging with Chewong: Some Issues Raised by Multitemporal Fieldwork.” In Malaysia’s Original People: Past, Present and Future of the Orang Asli, edited by Kirk Endicott, p.57-78. Singapore: NUS Press.